Drawing inspiration from her dual heritage, Peju Layiwola interrogates our collective social, political and cultural memory.

A product of dual heritage, Professor Adepeju Olowu Layiwola was born in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria in 1967 to Babatunde Olatokunbo Olowu of Idumagbo, Lagos, and Princess Elizabeth Olowu, daughter of Oba Akenzua II of Benin. Her mother, who was one of the pioneering students of the Department of Creative Arts at the University of Benin, is the first female to specialize in bronze casting in Nigeria. Inspired by her mother, Layiwola chose to study metal design at the University of Benin. There, she finished as the best graduating student in 1988. Subsequently, she established herself in academia beginning her teaching career at the University of Benin in 1991, from where she moved to the University of Lagos in 2002. She maintains an active studio practice and has exhibited in Nigeria and outside the country. She has spent decades conducting studies into Africa’s colonial experience and gender heterodoxy, which has resulted in exhibitions delving into the history of bronze casting in Benin, the legacy of the 1897 British ‘punitive’ expedition and the fight for restitution.

Layiwola is determined in her interrogation of our social, political and cultural memory. Her art and writing explore themes of history, gender, cultural appropriation, repatriation, and restitution. Currently a professor of Art and Art History at the University of Lagos, Layiwola’s determination to engage these parts of our collective memory is unsurprising. Her personal connection to a significant part of Nigeria’s history – a granddaughter of Oba Akenzua II, King of Benin (1933 – 1978) – also reinforces the art historian’s preoccupation with unveiling the country’s rich history.

In Indigo Reimagined, Layiwola opens up her examination into the ingenuity of the artistic practice of indigo dyeing and offers new perspectives on its interconnectedness with other genres associated with dyeing.

A mere thirty-six years before Oba Akenzua II’s reign, in February 1897, British forces had invaded, burned, and looted the ancient empire of Benin. The king, Oba Ovonramwen, was captured and sent into exile in Calabar, where he later died in 1914. The sacking of the empire, referred to as the Benin Expedition of 1897, led to the carting away of thousands of artifacts, including the famed Benin bronzes, to London where they were auctioned off, ostensibly to pay for the expedition. Many of the looted bronze heads, produced by her forebears, are still on display in several foreign museums today. Layiwola described the 1897 invasion as “one of the most traumatic experiences that occurred in Africa at the turn of the 19th century.’’

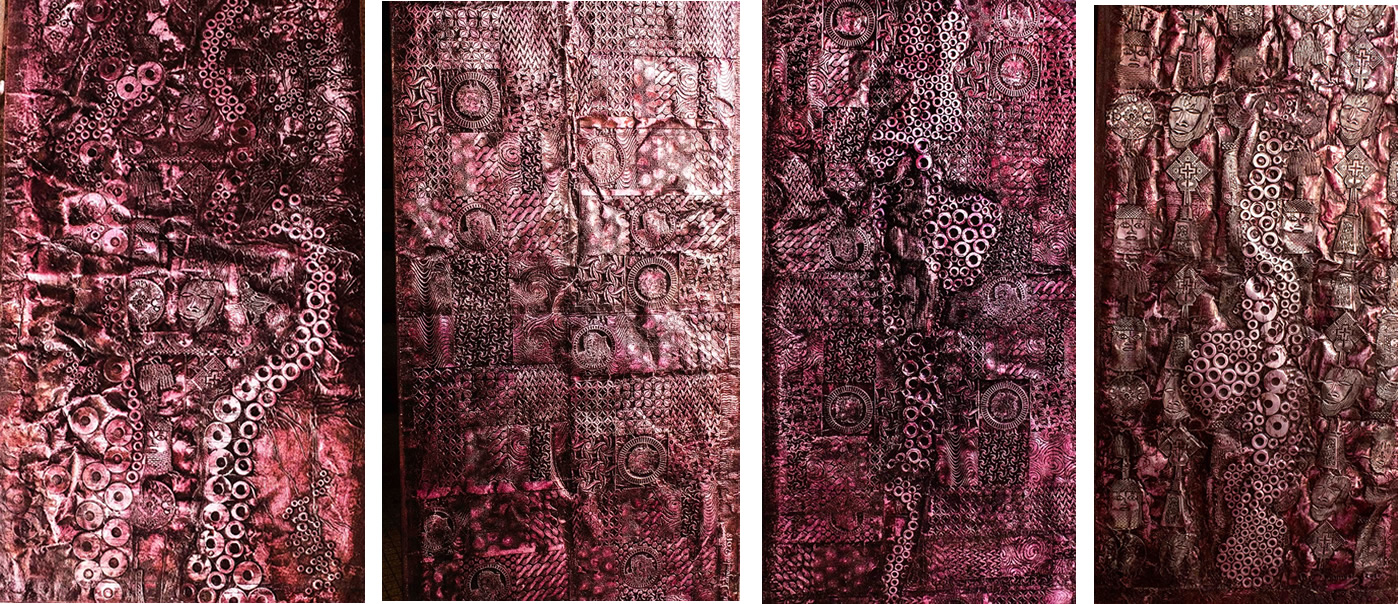

Her recent exhibitions include a number of provocative works in a variety of media—works like Dialoguing Sarahs (2018), a four-piece aluminum foil panel addressing the heinous crimes of colonialism through a remembrance of Saarjie Baartman, the South African woman who remains one of the most dehumanized and sexualized black female bodies in history; Face/off (2014), an installation of terracotta heads and plaques in the house of the head of the Guild of Bronze Casters in Benin city for the project, ‘Whose Centenary?’, which, choosing to remember the passing in exile of Oba Ovonranmwen, the King of Benin, who stood against British imperialism in the defense of his kingdom, questioned the commemoration of the British construct known as Nigeria. Another project of note is Benin1897.com (2009-10), a traveling installation of 1000 terracotta, animal horn, paper, beads, inlaid brass, and copper heads, addressing, among other things, the commodification of works of art looted from the palace of the Oba of Benin during the British expedition of 1897. This research project, Benin1897.com, was awarded the Departmental prize for the University of Lagos during the All-University Research Fair 2011.

In the 1920s, at the peak of Adire production, it was recorded that up to two thousand wrappers were being sold daily in Abeokuta alone. Two decades later, the decline in the artistic practice of Adire became inevitable with the influx of factory printed tie-dye designs.

Layiwola continues her interrogation of history with a solo exhibition, “Indigo Reimagined”, which opened on Thursday, 13 June 2019, at the Main Auditorium Gallery of the University of Lagos. The exhibition which highlights the beauty, richness, and complexity of the indigenous art form of Adire, the Yoruba indigo tie and dye fabric, is highly significant, not only for its focus on the artistic tradition of Adire but also for building on practical and academic knowledge of the art of fabric dyeing. The exhibition explores indigenous dyeing materials and techniques, levels of skill, multiplicity of motifs, the changing patterns of use, and its close association with pottery— emphasizing the use of pottery vessels in the dyeing process—and food—Yoruba staple foods, eko (corn starch) and cassava, are used for pattern creation.

As observed by Jean Borgatti, Professor of Art History, University of Benin, “… this time she [Layiwola] has moved beyond ‘Benin1897.com’ and ‘Whose Centenary?’ to a more generalized and shared African past focusing on textiles as a medium.” In Indigo Reimagined, Layiwola opens up her examination into the ingenuity of the artistic practice of indigo dyeing and offers new perspectives on its interconnectedness with other genres associated with dyeing. The fabric installation, Oje Market Day (2018-2019), is a huge, ceiling to floor, quilted wall installation made up of geometric patterned patchwork of blue, brown, and yellow ochre squares of traditional Yoruba textiles, aso-oke and black and white squares of contemporary fabrics. A concentration of blue squares at the end of the patchwork, Oje Market Day, underscores the artist focus on Adire.

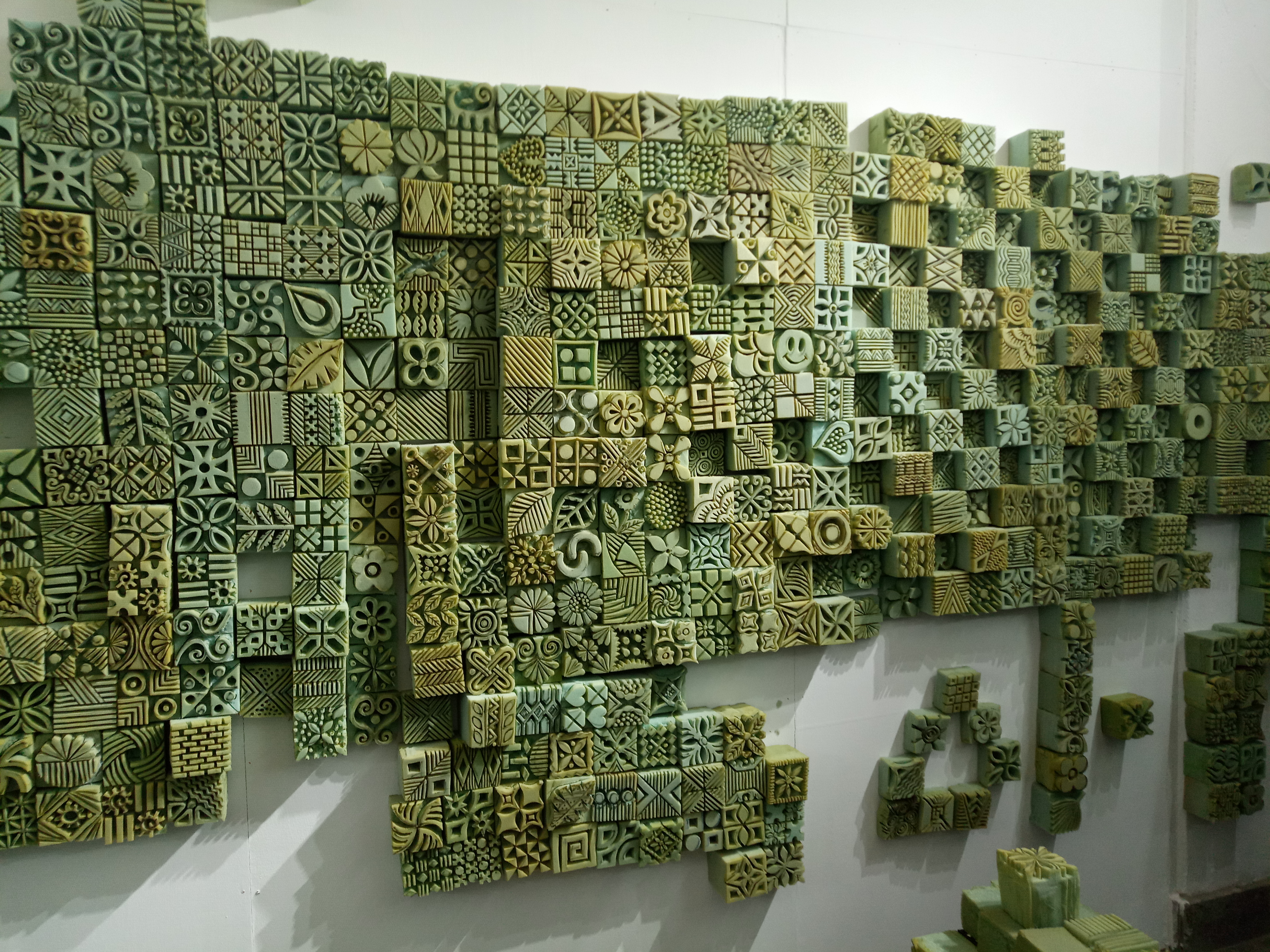

In addition to a number of smaller paintings and an installation of pottery printed with Adire patterns, the exhibition also includes two installations, Stamping History, and Orimipe. Both of these are materials intricately designed with traditional Adire motifs and a few contemporary symbols, like the smiley face. Stamping History is an arrangement of printing blocks made of Styrofoam, stuck to the wall and hanging from the ceiling. It calls to mind floating cities. While Orimipe is a collection of metal stencils strung together to create a see-through wall of elaborate patterns.

The Yoruba word Adire translates as tie and dye and refers to both the dyeing process and the final product. Yoruba oral literature credits the origin of fabric dyeing to Orunmila, the Yoruba deity of wisdom and divination, who was divinely inspired to create patterned cloths using the feathers of certain birds—indicating a relationship between the creativity and designs in Adire and religion. However, fragments of woven fabric dating back to the 9th century were excavated in Igbo Ukwu, while fragments of dyed threads and cloth recovered from the caves of Mali dates back to the 11th century. While we remain unsure of its origins, what we are sure of is that from the 1880s, the introduction of imported fabrics into Nigeria by British trading firms encouraged innovation in the art of Adire, as Adire artists found it easier to experiment with the softer, smoother fabrics of imported textiles. In the 1920s, at the peak of Adire production, it was recorded that up to two thousand wrappers were being sold daily in Abeokuta alone. Two decades later, the decline in the artistic practice of Adire became inevitable with the influx of factory printed tie-dye designs. By the 1960s, the indigo dyed textile had become associated with rural dwellers. Nevertheless, over the years a few artists continue to make efforts to keep this artistic tradition alive. One of its greatest advocates and practitioners is Chief Nike Davies-Okundaye, one of the Osogbo artists, who is credited with the contemporary revival of the art of Adire.

As an advocate of rejuvenating traditional artistic practices, one of Layiwola’s contributions to documenting local art traditions is The Women and Youth Art Foundation (WyArt Foundation). As far back as 1994, she was organizing workshops and training in various arts and crafts, including traditional crafts that are going extinct, for women and youths. This culminated in the registering of WyArt Foundation as a nonprofit organization in 2004. One of the foundation’s main accomplishments is its ability to reach a wider audience through its e-learning DVDs and magazines with step-by-step teaching of various arts and crafts. In 2017, WyArt Foundation embarked on a series of workshops re-introducing art to public secondary schools in Lagos State.

On her influences, Layowola wrote, “History plays a major role in the selection of material I explore in my work. My art is also inspired by my dual heritage of being Yoruba and Benin. I enjoy the advantage of sitting on the shoulders of one culture, and peeping into the other. Sometimes, I appear to sit on the shoulders of both and peep into the future. Much as I draw from these two great cultures, I am also fascinated by the ordinary and simple things that continue to inspire.”

Layiwola is currently president-elect and vice president of the Arts Council of the African Studies Association (ACASA). Among numerous awards and honours, she was the US Department of State Nominee for Cultural Heritage Preservation Program, International Visitors Leadership Program (IVLP) in 2011. She was also artist-in-residence, in the Arts of Africa and the Global South Research Program. For the project ‘Indigo Reimagined’, she received a Research Grant from the University of Lagos, 2018.

Indigo Reimagined is open until July 30, 2019.

Featured image: Peju Layiwola in front of her work “Even Mother’s Wrapper Couldn’t Cover”.Courtesy pejulayiwola.com