Some months back, the Female Artists’ Platform, an initiative of the African Artists Foundation had its annual exhibition and workshop in Lagos. The exhibition was titled “Design is the Personality of an Idea”, a combination of film, fashion, painting, photography, digital collage, and sound by eight diverse artists. The curator’s goal on this diverse collaboration was ‘to create full worlds with the precision and intentionality inherent in the concept of design’. They presented a worldview shaped by their experiences with the male or female being, distinct, complete, and in some cases more complex than the other. Five of the 8 artists – Nkechi Ebubedike, Modupeola Fadugba, Akwaeke Emezi, Nkiruka Oparah and The Venus Bushfires – are Nigerians, while the other three, Joana Choumali, Selly Raby Kane and Moonchild Sanelly are from Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal and South Africa respectively.

The exhibition generated arguments that led to many questions and sentiments for and against gender focus group exhibitions. One of it was, “if the artist’s gender is irrelevant in art, why organise an exhibition presenting works by female artists only?” One way to answer this question might be a reference to the concept of the exhibition itself. It was conceptualized to start erasing the notion of homogeneity in subjects covered by female artists. A mixed group exhibition could not have achieved this purpose. Another argument points that “an artist is an artist is an artist” and gender labels only diminishes the importance of the artist. This perspective is understandable and fundamental. The essence of female group exhibitions or any gender focus platform is not to diminish the work of women artists but to enhance their visibility in a market where their male contemporaries enjoy more representation and control. Whether this control is deliberate or an unconscious design by stakeholders is debatable.

Analysis and understanding of female artists’ works also suffer from poor interpretation. They are often limited to their femininity and a singular point of view. Looking through the works at this exhibition, there is no one way to describe what one sees, hears and reads.

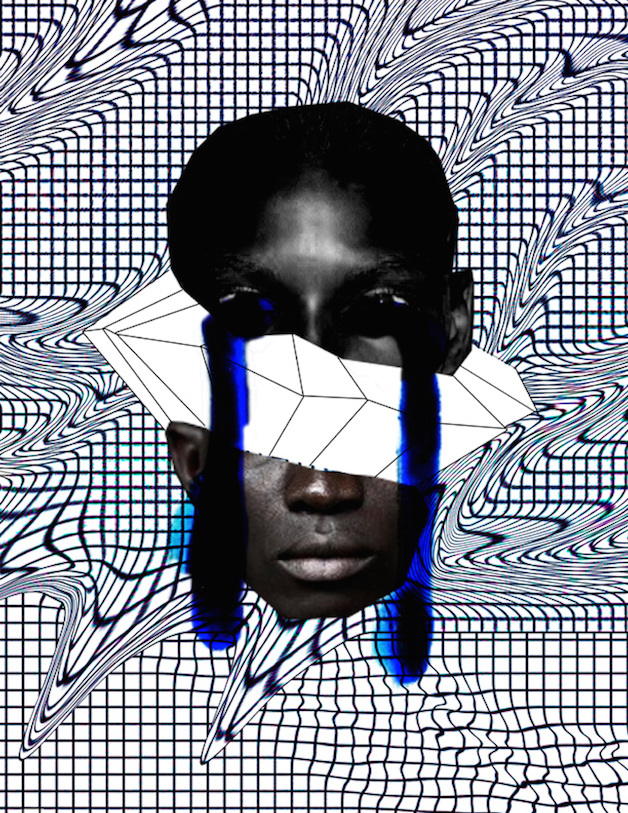

Nkechi Ebubedike’s The Bright Boys, for instance, is a digital print distorting stereotypical media images of the masculinity of American black men. She puts the images in a more positive context of form and colour, using her experiences with men elsewhere to paint a wider view than just the American one. Whereas, Nkiruka Oparah creates a remarkably personal and intimate space in a full exhibition room with digital collaged portraits on textiles, hanging from the ceiling. The layered portraits are accompanied by the poem Love, unrequited, placed on the floor beneath the works. While Ebubedike looks at a single subject from a global context, Oparah retreats into an inner space shutting the world out.

Modupeola Fadugba in 8 Days of Lazy also reclines into an inner space to reflect on her former understanding of the world without any pressure from the present. She calls it lazy, but it seems the colourful paintings are about her taking time to ‘reconfigure’ her mind. She invites the outer world to watch her evolution but without intrusion, and hope they find a connection between her art and their lives at some point.

Akwaeke Emezi’s short video portraits Ududeagu and Hey Celestial are dark, depressive and lonely. In Ududeagu, the monochromatic images look at the self in a state of loss and rejection through a male body in private spaces. The narration done in the Igbo language imitates the structure of folktale to place the invented myth in the film in a cultural context. Hey Celestial is also a reflective piece on depression and loneliness. It is based on a recurring character in the work of American novelist, Toni Morrison. Both works are texts translated to visuals from Emezi’s perspective as a writer.

Selly Raby kane, on the other hand, presents a dynamic world of fantasy where aliens would live among humans. The Alien cartoon is her contribution to the current burst of creative energy engulfing Dakar in Senegal. The innovative design on the dresses shows the unrestrained flow of creativity in the city. Raby Kane’s fashion creates a cartoony and surreal world.

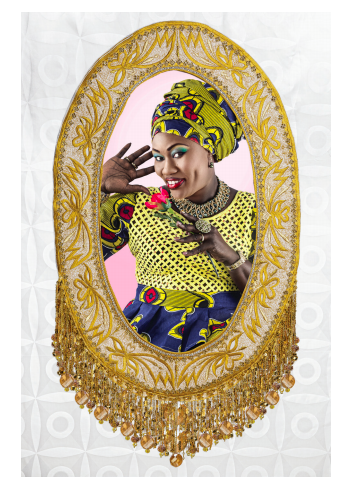

Whether the works are looking into exterior spaces or looking inward, the realities are still far apart. In Joana Choumali’s Adorn, unmarried low-class Senegalese women transform to elegant and iconic ladies in adorned portraitures. Their makeup and accessories present beauty in contrast to familiar images. In the documentary on Adorn, one of the ladies describes their ‘excessive makeup’ as what defines them as beautiful. They put up the ‘bling bling’ to disguise the true self and look perfect for the society. They enjoy the transformation and have invented ways to have the loudest makeup at every public ceremony. Similar gold frames in the portraitures were installed at the exhibition on a mirror; Choumali suggests visitors look into them to see their own reality.

Between the visuals are sound installations and music by The Venus Bushfires and Moonchild Sanelly. Listening to the sound installations, one’s mood shifts between ghetto funk and afro-folk music. Sanelly’s witty and playful layered genre addresses social ills, injustice, police issues, eating disorder, sex and other serious social problems. The Venus Bushfires with her special instrument – hang – and low melody music brings steadiness to the rhythm of the exhibition. Only the adventurous and curious eardrums will enjoy the music from both artistes.

There is no one work more outstanding than the other, there is no single story for all, they are all different. Each artist presents the reality and experiences in her world. The curator, Allyn Gaestel, points to this realization as the essence of the exhibition, “to leave the viewer with no one thing to say about female African artists”.

However, the question to ask is, are these works unusual, engaging and bold in design?