A dual review of Liz Johnson Artur’s exhibitions at The Brooklyn Museum and The South London Gallery.

I first heard of the photographer, Liz Johnson Artur, when her work was included in Grace Wales Bonner’s exhibition at the Serpentine, “A Time for New Dreams”, earlier this year. Although I couldn’t attend that exhibition, I was wildly intrigued by this somewhat obscure photographer who had photographed the global African diaspora for three decades. Eager to get a feel for Artur’s work, I immediately ordered her monograph online. As I flipped through the book’s pages – covered on both sides by gorgeous, textured woven material – I was left completely awestruck. But I was also overcome with a deep sense of confusion. Or, rather, a sombre disappointment in the artworld. I thought: how had I not [already] come across such moving work that captured, with an astounding documentative grace, the perplexing diversity and irreducible complexity of the global black experience? How had I not [yet] seen such powerful images that at once conveyed the enduring, everyday beauty, the effortless, improvisational style, and the hypnotic, jubilant spirituality inherent to black social life, while not forgetting the all-too-well known realities of psychic alienation, societal marginalization and physical/structural violence that impinge upon, but inevitably shape that life? “People – especially black people – need to see these photographs!” I thought. A few months later, when I learned the 55-year-old Russian-Ghanaian photographer would be the subject of two solo exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic, it occurred to me that others had been thinking this too.

Dusha, the Russian word for “soul”, is the title of Artur’s first solo museum exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in New York. The exhibition incorporates several photographs from Artur’s ‘Black Balloon Archive’ – a vast accumulation of images documenting her nomadic encounters with people and places over the last thirty years. In the gallery space, Artur’s photographs are installed in various forms and arrangements: at times conventionally, as a row of framed photographs on the wall, and other times less so, with Artur’s images encased in a three-dimensional glass structure (Book for Thought, 2018) or placed inside display cases on colourful, sensuous fabrics, (London Tapestry, 2018). Like the black subjects she captures, Artur’s photographs are, more often than not, part of a social grouping. Blackness, a collectively-rooted ontology, is thus enunciated through these images, which have more to say vis-à-vis each other than on their own.

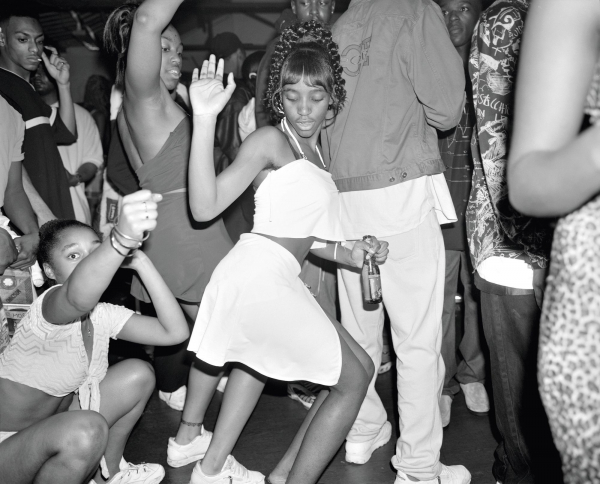

Not installed in any particular order that would be decipherable to the viewer, Artur’s photographs refuse to be read reductively in terms of a linear temporal progression or a fixed geographical setting. Rather, the photographer’s visual documentations, in their deliberate juxtapositions, give rise to syncopated rhythms – peripatetic vibrations – diasporic flows. In a section of Untitled, 1996-2012, two striking images hang next to each other. The photograph on the left depicts two black men in a hazy nightclub. One of the men, facing downwards and wearing a black pinstriped shirt, stretches out his arms to the shoulders of the other man, who is wearing a flamboyant, paisley shirt that has been left largely unbuttoned. Both men, whose eyes remain closed, seem completely lost in the music, swaying their bodies as if they‘re in the midst of a transcendental experience; the ecstatic ambience is further punctuated by the glowing white rosary that hangs from one of the men’s lips. In the photograph on the right, a black woman wearing an animal print top with white jeans assumes a contorted body position, her knees curled, her eyes closed and her back flat on a tiled floor. Is this woman exhibiting a killer dance move or has she been possessed by the holy spirit? Perhaps both? As the eyes dart between these geographically ambiguous photographs, the viewer observes black physical movement as liberatory performative ritual, black music as anarchic, polyrhythmic phonic material, spiritual yet profane.

These moments of otherworldly black joy form a dialogue with other exhibited works that illuminate the historic and ongoing struggles of the diaspora. The largest single image in the exhibition, Grenfell, 2017, reflects on the catastrophic event in which over fifty people (mostly brown and black) lost their lives to a fire at Grenfell Tower, a London council estate building, because of a lack of government oversight. In it, a ghostly arm juts out of a dark shadow into a bright ray of light. The allegorical demand for visibility and justice is felt more literally in a short documentary titled Real….Times, 2018. An older black woman at a protest, concerning the Windrush scandal, declares “We have the right to be here!”; a black man getting arrested by white police officers exclaims “Let’s break free!”; and a creative collective of young black women by the name of ‘Born N Bread’ (also the subject of another piece), is seen playing all kinds of black music out of a radio station in South London. All the while, Cassie Kinoshi’s free saxophone riffs play in the background between these cyclically-arranged scenes.

On the other side of the pond, at the South London Gallery is “If You Know the Beginning, The End Is No Trouble”. Artur has installed four photo-sculptural pieces in the space, each one a bamboo-cane structure incorporating multiple images from her expansive archive. In comparison to Dusha, this exhibition is even more highly attuned to strategies of display, as it prompts viewers to walk in and around the works, allowing for an experience that is as spatial as it is visual. Further, Artur’s multi-image installation method is re-deployed to produce an affective visual cacophony that reflects the infinite multiplicity of the African diaspora.

In Library, 2019, a tent-like structure, Artur once again displays her ‘sketchbook’ materials, which include magazine cut-outs, newspaper extracts, and musical posters, alongside the artist’s drawings and photographs. Her tendency to place these images on delicate, crafted materials such as felt and fabric imbues them with a domestic, personal aura. This, in effect, counters a quality specific to the photographic image, namely, its capacity for endless reproduction. In Peckham, 2019, the work opens up like a hallway with photographs of the South London neighbourhood and its predominantly black inhabitants on either side. Walking through the structure brings to mind the sensation of entering someone’s home and observing their family photos. But this ‘family’, although unmistakeably black, is multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-generational. The men wear suits, kaftans and tracksuits; they stare back at the viewer with their assertive gazes, sometimes obnoxiously, while posing in front of a car or donning a stunning black leather coat, and other times, with a look of quiet contemplation, as they sit patiently in a barbershop chair or hold up an Alton Ellis record in front of their impressive music library. The women equally impress viewers with their radical grace. An older woman walks the street dressed in iro and buba with a faux-Chanel wool scarf wrapped around her shoulders while another woman descends a zebra-patterned staircase wearing an all-burgundy leather outfit, hair to match. Other images document a black diaspora actively moulding its adopted environment, as posters advertising black hair styles, colourful bou-bous and Nollywood films grace the high-street’s urban-scape. Moreover, abstract still lifes of palm trees and arresting sunsets temper these vibrant scenes of black sociality. Crisp, black and white portraits also contrast with colourful, overexposed street compositions. These formally inventive alternations echo the irruptive rhythm(s) of Peckham, of Black British life.

Black style, in its unique negotiation of campiness and refinement is further elaborated in Women’s Corner, 2019. Resonating with PDA, 2018 (displayed at the Brooklyn Museum exhibition), Artur’s work features a close-knit community of London-based black queer artists and creatives. Outlandish dress and same-sex intimacy are to be found in this welcoming space for radical self-fashioning. Next to this piece is a circular hanging structure, Community, 2019, that documents weddings and spiritual gatherings across the diverse black communities of London – Christian and Muslim, West African and Eastern African. Like the two photographs I discussed earlier in the article, these images also unsettle the division between secular and spiritual black social practices. In either setting, an unyielding jubilance takes over the crowd; black bodies give into the music’s irresistible rhythmicality; draped garments move about, in concert with a celebratory motion. It always astounds me, that despite the plurality of dispossessive forces that confront us, both on the African continent and outside of it, we still manage to do everything with the utmost exuberance. Perhaps we’ve had no choice but to celebrate. How else would we survive in a world that has, and still, continues to makes our very existence unbearable?

Artur’s exhibitions are spectacular because they show that we, in Africa and its diaspora, continue to live and love in spite of the violence that gave birth to our global scattering. Her images narrate a non-linear story that reveals the phenomenon of ‘black genius’; that thing that makes it possible for us to sing, talk, dress, dance and worship in ways few others can. These exhibitions are also powerful because of their situatedness in two predominantly black communities, Brooklyn and Peckham. This way, Artur’s work is framed within its cultural conditions of possibility, allowing for the relation between audience and subject to shift from one of ethnographic fascination to one of familial kinship. Yet, her work excludes no one from accessing its affective power. Featuring themes and subjects from Africa, Europe, the Caribbean and the United States, Artur’s nomadic work materializes the infectious vibrancy and rhythmic sociality of black life.