In an obituary on Ulli Beier who co-founded the Mbari Club in 1961 with the involvement of young African artists and writers like Chinua Achebe, Uche Okeke, Wole Soyinka, Christopher Okigbo, Demas Nwoko, and Ibrahim El-Salahi, the Daily Telegraph noted that “the Mbari Club became synonymous with the optimism and creative exuberance of Africa’s post-independence era”. Although successful and notable, the club fell apart during the Nigerian Civil War (also known as the Biafran War) which broke out in the summer of 1967 and ended in January 1970. If the Mbari Club, in the words of the literary critic Toyin Adepoju, “brought together a constellation of artists whose work embodied the quality of transformation embodied by the aesthetic of creation, decay, and regeneration evoked by the Mbari tradition”, the post-civil war years led to the emergence of a new set of artist collectives, groups, associations and communities across the country whose work responded to the urgency of that time. In this current era, it is likewise important to understand what the artists and their work represent.

In Ayobo, a community in the suburb of Lagos, the Ayobo Colony was formed by the artists Ato Arinze, Babatunde Ogunlade, Akanimoh Umoh, Ankeli Christopher, and others, who are residing in the neighbourhood which is far away from the City’s art centre – Victoria Island, Ikoyi and Lagos Island. This sense of ‘community and togetherness’ has been critical to defining and refining the artists’ individual and collective visual identities.

Recently, an exhibition opened at the Revolving Art Incubator, Lagos, titled Salvage Therapy with the works of Ankeli Christopher and Abdulrazaq Ahmed. The former is a member of the Ayobo Colony while the latter reside in Ipaja a community in close proximity to Ayobo. Salvage Therapy focuses on some of the most urgent issues confronting the everyday reality of the Nigerian people – mostly the marginalized, and introduces the works of the two relatively new artists to the Lagos art audience. The exhibition also marks the culmination of years of artistic interactions between both artists, which began in 1999 when they met at the Ahmadu Bello University. Christopher was on an industrial attachment from Kano Polytechnic as Ahmed was studying at the university’s department of Urban and Regional Planning.

Ahmed’s encounter with the works of Gani Odutokun, a Nigerian painter and colourist, was a strong influence in developing his visual language which delves into his childhood memories of living in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state. Borno is in the northeastern part of Nigeria and the origin of the Boko Haram insurgency. Christopher’s artistic formative years were spent under the tutelage of Tonie Okpe, a professor of Sculpture at the Ahmadu Bello University, where he learnt to incorporate the three-dimensional elements of form and texture into his work.

Using display strategies, the exhibition curator, Jumoke Sanwo, puts forward the different stylistic approaches of both artists by placing their works side by side, as well as their approach to social commentary. Of the two artists, Ahmed assumes a more confrontational approach. The technical details of his paintings, such as the brush strokes, highlight the urgency in the brutality that engulfs his subjects. Christopher’s works seem subdued by similar experiences. He baits the viewer into slowing down to grasp the hidden messages of his works, and thus become aware of the intense feelings that define the subjects’ everydayness.

I began viewing the exhibition from Christopher’s Road to Elysium (2018), where the silhouetted figure in the middle of the canvas, draws the viewer into the piece. The curtain in the painting is being opened slowly, revealing details such as a doorway highlighted in yellow and the subject in a mood of contemplation. There is a web of threads, made from discarded canvases, across the painting which could mean being lost in the forested landscape of the work.

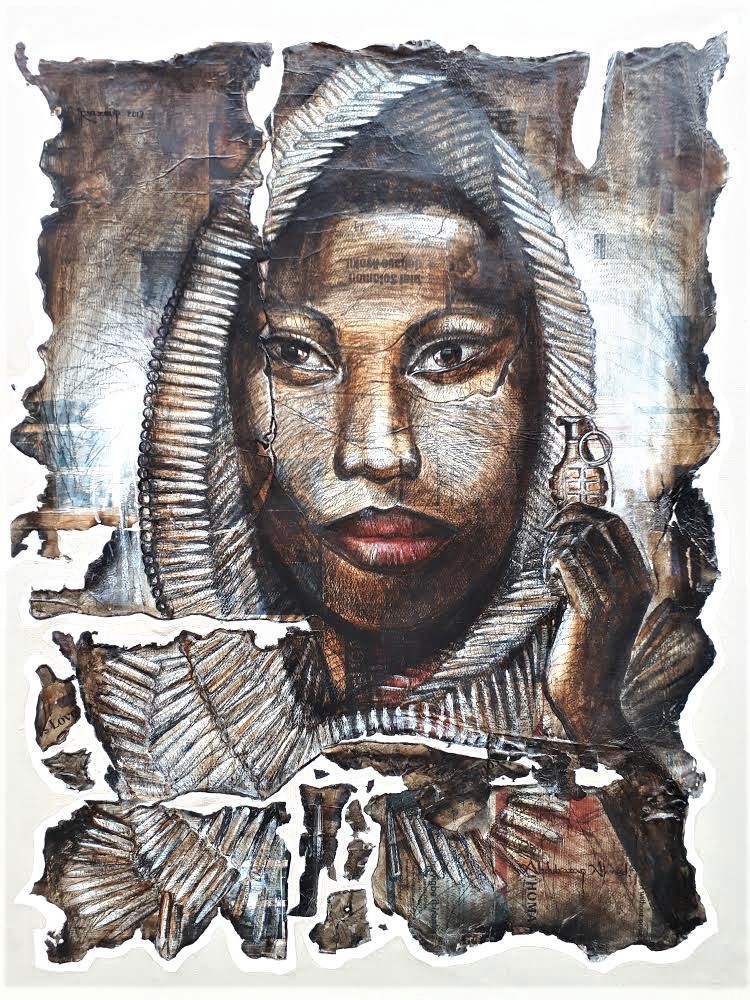

Materiality is central to the aesthetic experience in the works presented in Salvage Therapy. In the words of the curator, the artists have “developed an in-depth exploration of art savage, using diverse knowledge and skills to experiment and refine their use of material.” Christopher makes threads out of discarded canvases into human and abstract shapes and forms as well as make use of a variety of found objects such as sponges, fabrics, combs, and scissors that are immersed in colour and sawdust, and then splashed across the canvas. For Ahmed, the starting point is the newspaper archives which he glues on the canvas, burns and begins painting on the burnt surface which also gets glued to a new canvas. As the unknown starts becoming familiar in Christopher’s works, that is, the adorned subjects in richly textured surfaces and lines, Ahmed’s multi-layered canvas becomes undulated.

On encountering the portraits made by Ahmed, the parallels in the works of hyperrealist painter, Babajide Olatunji’s Tribal Mark Series jumps out. Although Olatunji’s Tribal Mark Series is inspired by the scarification marks amongst the Yoruba people, Ahmed’s focus is on the aesthetics of adornment and the features of northern Nigerian women. The eyes of his subjects are as powerful as in the former’s oeuvre but are somewhat drowned in the newspaper materials. For Olatunji, the marks allude to the perceptions of beauty and identity in the Yoruba culture while Ahmed makes shallow incisions across the canvas which is the subject’s skin. In no work is this more apt than in The Storm Is Over (2018) where the vertical lines running across the portrait reveals not only the hidden layers of the canvas but the subject’s vulnerability.

In the works Path of the New Proselyte (2017) and Quest for Glory (2017) by Ahmed, displayed on the first floor of Revolving Art Incubator, the eyes communicate the beauty of the subject and also draw you into the sadness that engulfs her – both paintings share the same subject and are framed in rough edges. Whereas the former is victimized – adorned with bullet holes and a grenade on the forehead, the latter puts her in a position of power – the grenade is firmly placed in her hands and there are no bullet holes.

John Ruskin, the eminent 19th-century English art critic wrote, “Great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts – the book of their deeds, the book of their words and the book of their art.” In our time, we need the artists whose voice will shape the consciousness of the people, especially on current political propaganda and shenanigans. Instead of making craftsmanship the ultimate goal, will it be possible for our artists to shift their ‘expertise’ to evolving the issues inherent in their works?

. . .

Salvage Therapy is showing at the Revolving Art Incubator (2nd floor, Silverbird Galleria, 133 Ahmadu Bello Way, Victoria Island, Lagos) from 14th July to 2nd September 2018.

Images featured are courtesy of the Revolving Art Incubator.