Phoebe Boswell’s exhibition “Here” powerfully explores alternative ways to engage in the present and formulate new dreams for the future.

After months of Covid-19 related disruption, Phoebe Boswell’s long-awaited exhibition “Here” opened at the New Art Exchange in Nottingham in May. The show weaves together a wide range of investigations into subjecthood, womanhood, representation, and migration. These are recurring social themes in Boswell’s multimedia practice. But with “Here”, they have been masterfully deployed through drawings, animations, and installations to vibrate to the rhythms of sensory-stimulating soundscapes. Moving through the four rooms of the show feels like riding a wave. The exhibition is at times enthralling and awash in emotions. At other times, it takes a quieter tone leaving us to contemplate the harsh realities of the present and the possibilities that lay ahead. If only we wielded language differently, if only we took the time to see, if only we mobilised our bodies in new ways.

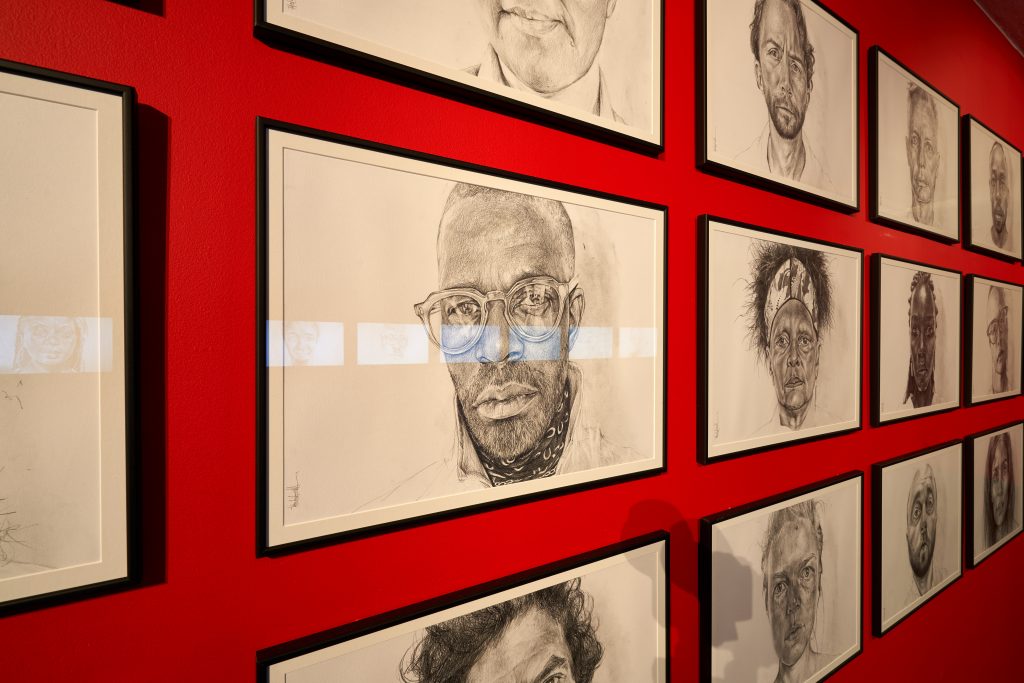

“I am a citizen. It’s time for new dreams.” This declaration appears briefly on a screen when a sitter’s filmed portrait is complete. After that, these words make space for a new face, a new portrait-in-progress, and a new statement by a different sitter in a looping video installed on eight screens. Thirty-one portraits on paper are displayed on the opposite wall to complete the video installation. They are titled “I am”. Though simple in appearance, “I am” is vibrantly animated with progressive ideas of self-definition and a collaborative process between the artist and sitters. The curatorial team has deftly harnessed these ideas to shape the visitors’ experience with a participatory wall where one can complete the sentence “I am”.

“I am a survivor”, “I am hungry.” These pronouncements resonate like an indictment of the neo-liberal system, whose limitations have been exposed by the pandemic. Other statements such as “I am spirit”, “I am intrigued” read like a rebuke of the hyper rationalist vision of the word that traces its roots to the French philosopher René Descartes’ famous assertion, “I think therefore I am.” It was, he wrote at the time, the only belief one could be sure of. Away from rigid certainties, these contemporary formulations of “I am” scribbled on the wall open tiny windows onto other belief systems, alternative ways of being in the world, filling the crimson space with feelings of expanded possibilities.

The mood in the second space offsets the lingering haunting feeling from the first gallery. The show opens with “Transit Terminal” (2014-2020), staggering representations of twelve women, men, and children drawn in charcoal on the back of coffin-looking rectangular wooden boxes. Whilst airports are usually flooded with light and buzzing with constant movements, Boswell’s terminal is immersed in darkness and frozen in time. The emotive installation reminded me of Warsan Shire’s poem “Home” and this particular verse:

no one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying-

leave,

Leaving has brought them to this dark place where only birds drawn on walls are free to move, unencumbered by considerations of borders. Somehow, amidst this anguish, I felt a sense of reprieve in how they have been depicted. Boswell has stubbornly refused to serve up their despair for consumption. Instead, the subjects are captured standing, with their backs turned to their homes and firmly to the viewers. Even when they are caught looking to the side, the artist has still denied access to their faces.

Black bodies captured in a state of crisis are sadly common sights. And the counter-narrative has often being limited to depicting black people as “Queens” and “Kings” or wealthy self-possessed subjects. It generates a stale visual discourse that fluctuates between two extremes: objectification and sensationalism on one side and salvation through wealth and kingship on the other. Boswell swerves both impulses and speaks in a language of subtlety. Hurriedly leaving home translates into the absence of luggage. The long road already travelled is visible in the many creases in a piece of clothing. To hear her and the nuances of the stories she tells, viewers have to pay careful attention and look closely. They also have to listen intently even if the listening part is sadly disturbed by the loud pop music from the café. On the day I visited the show, Boswell was there, doing what her work required of the visitors. She looked intently and asked attendants to turn down the music and close doors to preserve visitors’ experience.

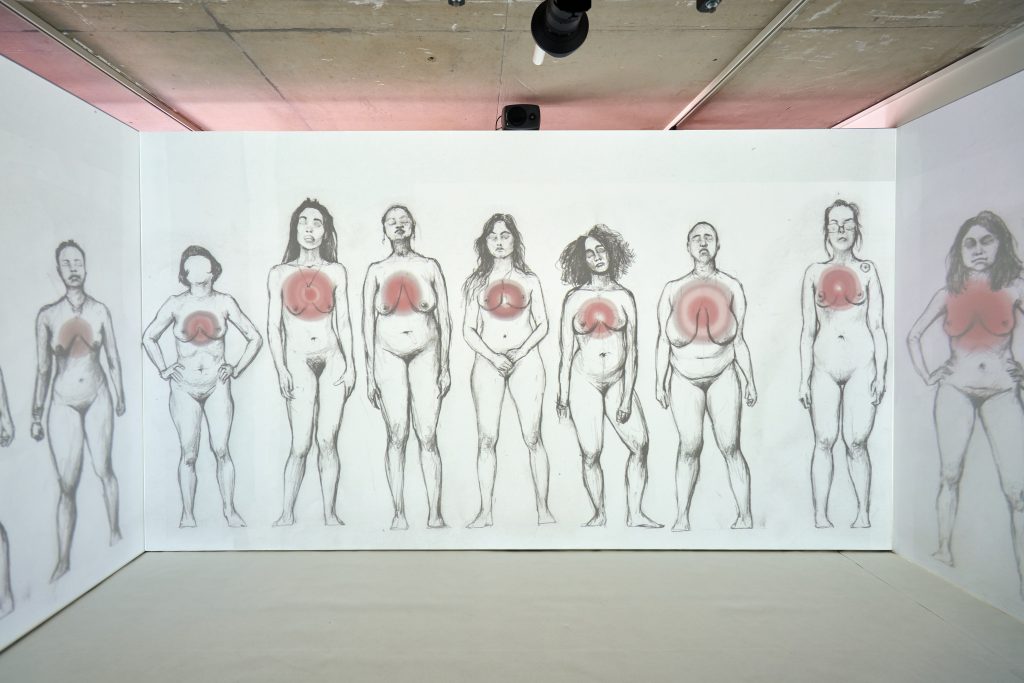

For all that is on show downstairs, the masterpiece is upstairs. A closed-off, all-white space reveals a battalion of animated women on four walls, armed with their sole weapons, their naked bodies. With “Mutumia” (2016), Boswell re-enacts the customs among elderly African women walking naked in public as the ultimate form of protest. Nudity here is not a visual fodder for voyeuristic consumption as it has been at times in art history. Instead, it is the quintessential expression of agency and solidarity among women. These women, still at first, are activated by the movements of the visitors. With three of us in the room, it is an orchestrated delight. They come alive, move, and transform their bodies to express their vexations. The readings and evocative songs turn the visual installation into an incantation that transcends the realm of the here and now.

“Your silence will not protect you.” Boswell draws inspiration from Audre Lorde’s quote and explores the function of language in the third space of the show. But it is another Lorde’s quote that came to mind as “Mutumia” came to an end. “The white fathers told us: I think, therefore I am. The Black mother within each of us – the poet – whispers in our dreams: I feel, therefore I can be free.”1 The connection to our feelings and bodies is what might pave the way towards new dreams and freedom.

1 Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, 4.

Beautifully written to reflect am extremely talented artist of our generation.

Every element of a Phoebe Boswell exhibition always feels contemplated and with heart.

Her sensitivities are expressed from way deeper than solely the art on the walls.