The violent eruptions that accompany earth’s volcanic activities sometimes lead to fatal results when humans are in the way of nature, but they are also responsible for some of the planet’s most beautiful landscapes. Such is the case of Jos Plateau, a place of breathtaking beauty, whose formation has also imbued with an abundance of materials, including tin, which was aggressively mined to the point that it has left the beautiful landscape pockmarked with ponds and gullies. It was these man-made formations that grabbed the attention of Abraham Oghobase, who, as recorded in Emmanuel Iduma’s Sum of Encounters, “while in an airplane, descending towards Jos for a visit to his wife’s family, he saw a cluster of mining ponds, which he thought were beautiful.” And it was from that moment of attraction that the works in Layers of Time and Place: What Lies Beneath were born.

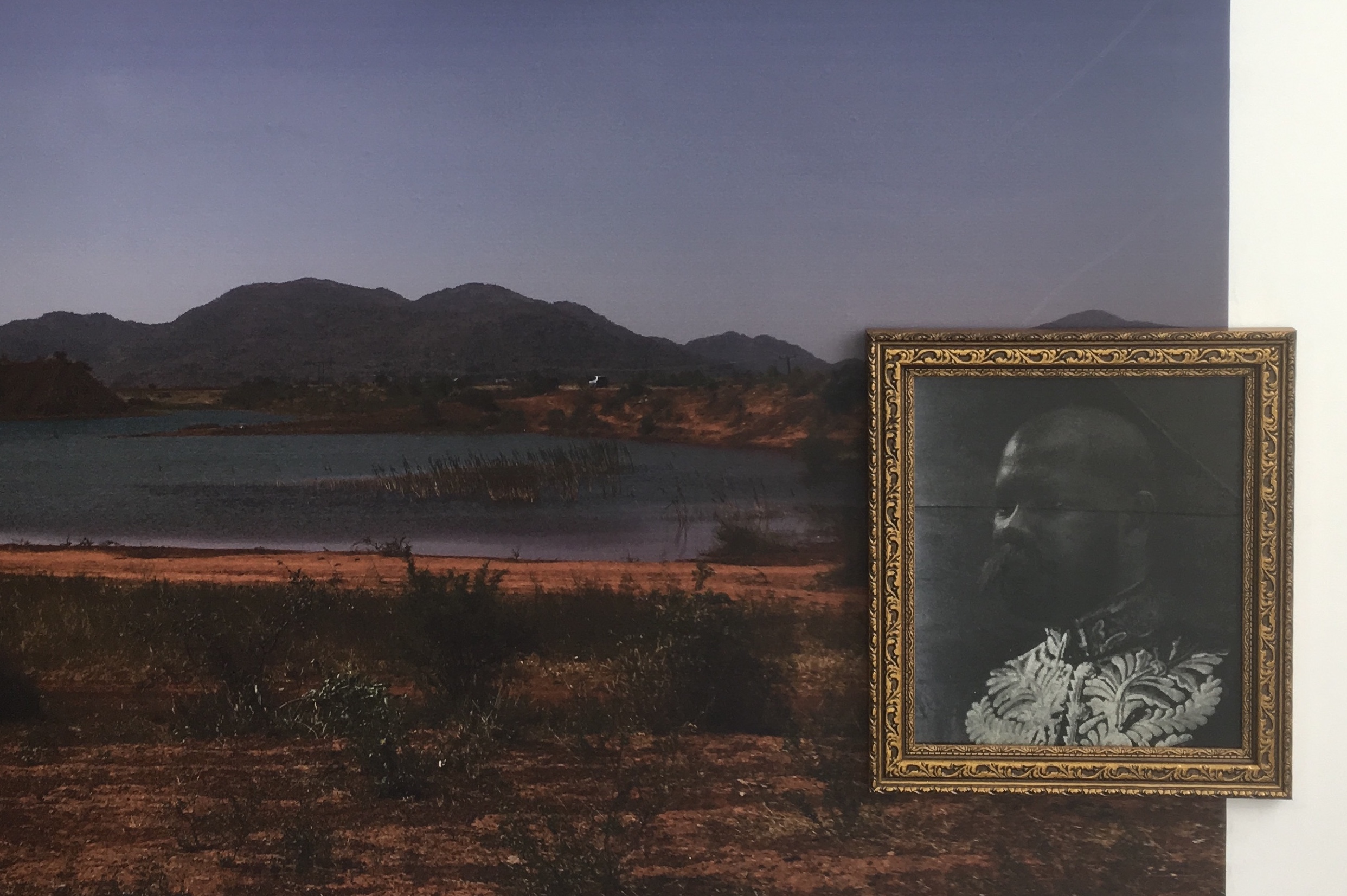

Oghobase employs every tool in his artistic arsenal—photography, photo manipulation, a collection of found objects—to create a meditation on the impact of human activities—mining in particular—on Jos. The exhibition is primarily a conceptual art installation which combines a series of iterative self-portraits, an array of collected rocks, and manipulated photographs that either transform Oghobase’s portraits into colonial-era style monochrome photographs with the artists himself in the image of the colonialist or lithographic prints that superimpose the Jos Landscape with images from Europe.

The most prominent aspect of the exhibition is the landscape photographs, which capture the vastness of Jos, its beauty and emptiness. They depict ponds and excavation pits left by the mining of tin and machines and rail tracks that have descended to disuse. One of the more striking photographs is that of a building that looks like a ban but could just have been a warehouse or storage of some sorts. It is captured in monochrome, which gives it an appearance of timelessness. Not only could this have been taken at any point in history, but it could also have been taken in any industrial city with a history similar to Jos. There is still minimal mining activity in and around Jos, as some of the photographs show, however, what is left isn’t frenetic energy that one might attach to such industrial activity, but the carcass of a practice still in the throes of death. There are abandoned rails that at one time must have ferried the mineral resource out of the mines, offices that reflect the bureaucratic support the mines must have needed, and heavy machinery abandoned, standing tall in open fields like relics of an alien invasion. Oghobase photographs all these with a devotion to the picturesque tradition of landscape photography. Viewing the photographs, one arrives at the understanding that a land which has been visited by exploitation that has left it barren can still carry some form of beauty, even in its brokenness.

If viewed for their mere documentary purposes, Oghobase’s pictures show environmental devastation that should fill the viewer with sadness, yet looking at his photographs evoke quite the opposite. Perhaps because beauty was what prompted his attraction to these sites of devastation, Oghobase’s images retain what is indestructible about beauty, the kind that recalls Susan Sontag’s assertion that “Beauty (should you choose to use the word that way) is deep, not superficial; hidden, sometimes, rather than obvious; consoling, not troubling; indestructible; as in art, rather than ephemeral, as in nature. Beauty, the stipulatively uplifting kind, perdures.” In these photographs, I experience a feeling that asserts the understanding that products of the destructive nature of humans can be stark but beautiful. And that beauty isn’t a mask for the horror they stand testament to. “Jos, a tin mining town whose occupants claim their land is devastated with nothing to show for it,” writes Iduma, “is no less pretty than a smiling villain.”

The story of mining in Jos started in the 1900s when British colonialists explored the land in search of mineral deposits. In the 1970s and 1980s, however, the machine efficiency left by the Brits was replaced by the shoddiness of Nigerians, whose artisanal mines escalated the environmental damage inflicted on the land by the mining activities. By putting himself in the place of British colonialists through manipulated monochrome portraits, Oghobase reflects this history of exploitation: from the perspective of the land, there’s scarcely a difference between the locals and the foreigners.

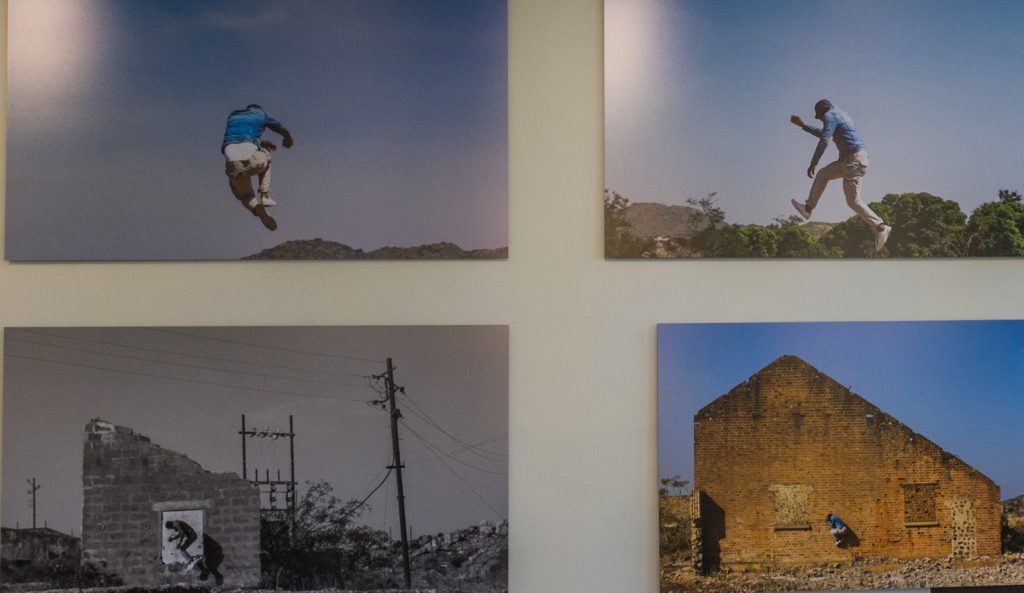

The effects of mining on Jos are not merely ecological, but also social. The constant erosion of the land has left its people in throes that are compounded by other crises that have visited the beautiful city. Oghobase uses his self-portraits, which recall his past work in Ecstasy and Untitled, to depict this reality. In a pair of photographs, he’s leaping off the ground, his back to the viewer and under uniformly-blue skies. And in another pair, he leaps up with his body in a foetal position—that quintessential representation of pain—against the backdrop of a crumbling wall. With these self-portraits, he transmits the psyche of those living on these lands: even if the land is beautiful, the pain visited on it by years of exploitation linger.

Taking the environmental and architectural elements of Jos and combining them with physical interpretations which place the human body in these sites, evokes similarities in the work of Oghobase and that of Congolese artist Sammy Baloji. Baloji’s contemplations on colonialism and post-colonialism challenge the viewer to think not just about the staid history of our people that we’ve been taught, but also how the things and people we see around today carry echoes of that past that can tell a different story and show that these activities haven’t really ended but simply morphed into different manifestations.

In the sub-series titled What If Austria Had Colonized Nigeria? Oghobase imagines an alternative history of Jos. He superimposes the landscapes with images of Austria using the lithographic technique. Colonisation, like volcanic eruptions and industrial processes, is as ecological as it is human. It is terraforming by an alien people, which leaves original inhabitants of a land feeling like strangers in their own home. There is vivid proof of this around the world, perhaps nowhere as dramatic as the island of Hispaniola, which the French and Spanish split into two colonies to become Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The two countries are on the same island whose landscapes have now become so different as to become separate ecologies, and the people are now forced to see one another as fundamentally separate even when they’re not. This series remains a work of the imagination, because Austria had no chance to colonise Nigeria, yet it creates the space for other hypotheticals. What if the British never colonised Nigeria? What if tin was never discovered in Jos, Plateau? What if? These questions do not have definitive answers, but as long as Africans wrestle with the impact of colonialism in a supposed post-colonial world, imaginations capable of projecting alternate realities beyond the present bleakness have to be developed.

In September 2018, a black Toyota Corolla car, which had been driven by Major General Idris Alkali, who had been missing for weeks, was found in a mining pond at Du in Jos South Local Government Area of Plateau State. This was after the pond was drained by military personnel, in spite of protests by women in the community. In that pond, the industrial past of Jos collided with its violent present. Residents of the communities feared military reprisal attacks. The military promised that all they want is cooperation. Three more cars were found in that pond, which residents attempted to explain has always been a death trap for cars.

Oghobase’s exhibition keeps that September 2018 event in relief. Here are landscapes, buildings and bodies with layers that time has imprinted with history. Excavating these layers, Oghobase’s work becomes an archaeological event that examines the past focusing on one moment in time, and demanding that we pay attention to the oft-unacknowledged effects of human history.