Two writers connecting on their presence in the world of arts and culture, re-examining identity and success, and discussing a contemporary art scene swamped with hyperrealism.

At first, setting out to have a conversation with Wana Udobang, journalist, poet and documentary filmmaker, and Emmanuel Iduma, who identifies simply as a writer, seemed odd for TSA. But it turned out to be a very stimulating adventure. Perhaps, it was spurred by the scenic view and energy of the space we sat that morning at Bogobiri in Ikoyi, Lagos, the restaurant cum cultural event arena, where many creative talents have been nurtured and brilliant performances experienced.

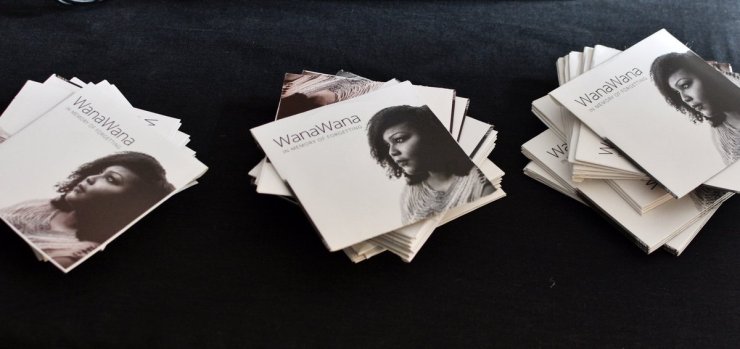

Driving discussions on personal and collective realities that are usually not questioned or addressed openly are the stuff of Udobang. She is interested in issues of social justice, women’s rights, religion and culture. Beyond her journalistic work, the intersections between these manifest in her poems and short films, where she brings to the fore deep personal stories of trauma, love and everyday dilemmas that are rarely addressed in the African society. Working in many fields including writing about the arts, Udobang has contributed reports and essays to The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Africa Report, Index on Censorship, and Broadly among others. She has received a number of fellowships including the International Reporting Project (IRP) Fellowship and the Gabriel Garcia Marquez Fellowship in Cultural Journalism. In 2017, she released the poetry album In memory of forgetting.

Possibly more introvert with gentle and easy vibes, Iduma is a writer of fiction and non-fiction literature, and author of the recently published travelogue, A Stranger’s Pose. Not keen on being called a critic, he is a faculty member at the School of Visual Arts, New York, where he received an MFA in Art Criticism and Writing. He has contributed essays on art and photography to the journals and magazines ARTNews, Guernica, Art in America, Hyperallergic, ContemporaryAnd, BOMB and the British Journal of Photography. On his blog, A Sum of Encounters, he publishes intimate portraits of artists based in Nigeria or the United States. He was the associate curator of the first Nigeria Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia in 2017.

Have you read: With All The Freedom That We Have, What Are We Saying?

Bukola Oyebode: Can we discuss how you two see your work intersect? You work in ways that are very similar, threading the thin line between fiction and journalism. Although the forms you engage are somewhat different, your works are also very similar.

Wana Udobang: I think the one thread that runs between both of us is that we like ideas. I think we have a thing for ideas, conversations about ideas, deconstruction of ideas, how those ideas connect to art, and how those ideas intersect with our everyday living and functioning.

Emmanuel Iduma: I agree. For me, the question is not whether I am a writer that writes, whether I am an art critic that is interested in film making or in journalism, or whatever. I am first and foremost a writer, so I can do anything with that. I think that is also a point of intersection with your practice in general. You are not limited by genre, which is a hard thing to do.

WU: Yes! I would like to ask you about that as I feel from the outside world, especially being Nigerian, you are always expected to be just one thing. For you, is it a thing of interest or boredom, or do you feel like different subjects require different mediums?

EI: It is, actually, what voices am I listening to while trying to write? Another is restlessness. I really admire people who can work on one project for twenty years. It is the most fascinating thing to see people who can sit down with one project, one novel, work on it for seven years and do nothing else.

BO: How do you decide which story to develop as fiction or journalism? I observed you are both more relaxed in the literary and creative space which probably allows stories that you are not able to publish in journalism. How do you make this separation?

WU: Sometimes, it is access. When I wrote fiction, I felt that I was not imaginative enough because I took people’s stories that I already knew and somehow fictionalised them. I think that is a factor, but it is not always the factor. I also think that fiction can help you explore certain kinds of complexities in a different way. It is not fixed per se.

BO: Would you say the deciding factor is subject to how the story or the idea is eventually published and where? Because certain stories will not be allowed on certain platforms, you may decide to use as fiction to be free to express the idea or the story in that medium.

WU: Maybe. Sometimes it is what medium will be more compelling to tell that story. Some stories are so real and vivid, and you already have access to the characters, saying, “Okay, use my name. Put me in front”, and that works for journalism perfectly because we don’t have restrictions. As you know, I write poetry as well, and poetry has another way where you can just break down things. Literally open stuff up in a very different way. It’s not something I overly think about. I think that the ideas and the subjects find a way to dictate what medium best suits them.

EI: I will agree with that. The kind of writing I started with was poetry and fiction. Dami [Ajayi] asked me the other day, “When are you going to publish your book of poems?” And I said that will be my tenth book. I started from poetry and concurrently fiction but around the time my novel came out in 2012, I started participating in the Invisible Borders Project and that required writing non-fiction. There was an immediacy to the experience that had to be articulated on the blog while travelling. That was, at least, the first most cohesive attempt to write something outside fiction, and that was because I was travelling. I had stories unfolding in front of me. But, it has gotten more complicated in the time since then. Most people forget – or they don’t want to think of me as writing any other thing but essays – and I think that is going to change very soon. It has taken me all this time to come to a place of almost clarifying what my ideas are. And once I have clarified those ideas, I can take it to any medium. The urgency of writing a novel now does not come from just the story but also what kind of ideas I am trying to convey through this medium that would otherwise not be as urgent if I am writing an essay. An essay is kind of more urgent. You want to communicate in an argumentative manner.

BO: It is also time bound.

EI: Yes, it is time bound. You are writing a review, you are publishing an interview, you are writing a hybrid essay and fiction, you know there is a certain word count, and there is also a commission. All the deadlines insist you have to send something. But then with the novel, you take all the time that the story requires to unfold and I think that is one real distinction for me.

WU: I want to ask you, do you feel because of the way you work now, your ego is no longer in the work?

EI: I got goosebumps when you asked that question.

WU: I asked because sometimes when I am communicating with other people who are fixated on writing a novel or doing one thing, they project that on you and it affects you. You may begin to ask yourself when you are going to write a novel, or when you are going to do a collection of poems. But, I don’t feel the need to, yet. I don’t feel any obligation. I say to myself, I will write a novel when I feel like it and have a story that is important to tell. Also, I find that my ego is not involved in wanting the praise of it. I don’t think it validates my skill, interest or discipline.

EI: Or your sense of what is important in the world. It is probably the most important question that I will address today and I will tell you why. It is connected to everything. It is one of those questions when people ask, “Are you working on a novel?”, and I say, oh, but in the last five years, I have written at least forty essays. That rigour, that kind of euphoria that you associate with a novel or fiction, can’t you, let us say, decolonise your mind to apply that to everything else. But I think this question comes up particularly because novels are the most visible genre for the market.

BO: When you say visible, what do you mean?

EI: Well, yeah! If you write a good novel, you are more likely to…

WU and EI: …have a career out of that as a writer.

EI: Just one good novel as opposed to…

WU: …with everything else.

…the ultimate goal of being a writer is to speak to the world in a way that it doesn’t have anything to do with me… the sublimation of my image. And it is not that I am not telling a story that is from my life, it is simply that I am looking for a point of intersection with the world.

BO: Do you think this validated people like James Baldwin? He wrote a lot of essays and novels. Same as Toni Morrison. Perhaps, this does not apply to Susan Sontag who wrote mostly essays. I want to assume they did not need the success of a novel to validate their other works, especially what they had to say.

EI: Well, I do not necessarily agree. I won’t talk about Baldwin’s validation because a lot of things that have happened in relation to his body of work have happened because of the passage of time, the fact that he is dead. When you think about his career—I might be wrong because I have not checked this, and maybe we should, in fact, check—what book did he publish first? That’s really what we are talking about. The way it works now is you have to write a first good novel, and then you are celebrated as a writer. But for us who think about it in the opposite way, I am more interested in the culmination of my life’s work. When people ask me these kinds of questions, I say ask me after my fifth book. What is my status? Or what is the degree of my visibility? Ask me after my fifth book. You have to remember that Toni Morrison’s Beloved was her fifth book.

BO: I can understand your points about ego and validation in relation to publishing novels, but can you explain further how these affect you directly, even as well published writers?

WU: Because I am constantly being asked. At Ake [Book and Art] Festival, the first two years, people repeatedly asked: “Where is your book?” “What is your book?” When I respond that I don’t have a book, they go on to ask, “Why are you here eating with us?” This also came up when I went into making poetry albums. Similar questions were asked: “When is the book coming out?” Some even suggested making all the poems into a book. But, I am just interested in the idea of experimenting with poetry in an interesting way with sounds and how people who will probably never pay attention to poetry can be gripped. For me, it is really about experimentation, not making a book or not.

EI: Back to that question you asked earlier, the ultimate goal of being a writer is to speak to the world in a way that it doesn’t have anything to do with me. It is almost, as someone said, the sublimation of my image – getting to the point where if I am writing in the first person, it is not about me. And it is not that I am not telling a story that is from my life, it is simply that I am looking for a point of intersection with the world. How can you look at the world in a way that has nothing to do with your own peculiar experience but with all the potential points of intersection between your life and the lives of others? If you start from that point, then it can apply to anything. It is about removing myself from the picture.

WU: You want to become transient in the story.

BO: I like your idea about writing from the point of our shared humanity. It is thought-provoking. We have established you both like to engage ideas and like to develop them into unique (and tangible) experiences around you. Can we talk about the ideas and markers that come through and matter in your works?

WU: Trauma is a very huge one that comes across in a lot of my work. I suppose within that box of trauma, I am interested in how experiences change people and how our bodies adapt. There is something called epigenetics, used to study people who have been victims of the Holocaust, like their great, great grandchildren, and how the trauma becomes embedded in their DNA even when they give birth to children. The same thing with African Americans and slavery. I am very interested in how some of these experiences alter character, living through this adapted pain, and what it does to human beings.

EI: This a very interesting question to answer. I think I am at the point in my work where things are coming together. As a prefix to answering, I recall saying to someone recently that I think I have found my voice. Immediately I said that it occurred to me how terrifying that very idea is. To say that you have found your voice, after many years of work. But, I meant that in the sense that now I know the kind of work, the kind of writing I want to do. I don’t want to put it in an amount of time, but maybe in the next three books, I know what I want to write. But to answer your question, I will talk about my new book A Stranger’s Pose, which draws from my travels.

While writing the book, I was thinking about the meaning of estrangement. How you are in a place for a very brief moment in time, and you become intimate regardless of the brevity? The idea of an intimate stranger, which was a defining attribute of my journeys. If I look at it from a retrospective point of view, my life in general – because I didn’t grow up in one place in Nigeria – was always a question of, what are you? Iduma is not an immediately recognisable name so people can’t really tell where I am from and my accent does not betray that. This is the fact of my life as far back as I can remember. I didn’t speak Igbo well enough or I did not identify in a way that was properly indicative of my ethnic group, which is a very terrible idea. As Toni Morrison argues that racism precedes race, I want to start making the argument that ethnocentrism precedes ethnicity.

The central idea of the book is that of the intimate stranger. How can you become intimate with a space without necessarily being a local – an indigene? Whatever you want to define that marker of authenticity as.

…creativity is really about peeling layers off, reassembling and breaking…the world of creativity is imagination and saying what is possible or what is not. You cannot create or make honest work without having to interrogate.

BO: I want to refer to a text you wrote in The Colonizer’s Archive is a Crooked Finger, which makes me see how you question identity, especially in relation to the postcolonial definition of who we are as Africans. You wrote, “Those who solicit identities from the past do not understand how their lives might have unfolded differently.” Don’t you think they do this with the persistence of finding the faintest reflection of who they are and could become? Although, I see this as fetishising what could have been without the intrusion of colonialism, and this makes me ask, what are we really looking for that is not in existence anymore?

EI: The tragedy of colonialism is that the disruption that happened – Achebe calls it “breach of continuity” – was such that it sets you on a different course. What colonialism did was to imagine the future for you, a future that you had no hand in determining. Of course, all kinds of things have happened. We have taken back our agency, we are taking back our agency, but when you want to think about colonialism squarely, you are thinking about a situation where your future was stolen from you and…

WU: …and determined for you. Even if we don’t know, I think we are in search of what was.

BO: Indeed. It is as if we are constantly trying to grasp what was taken.

EI: Absolutely! This is interesting because you know the famous Proust’s book, In Search of Lost Time, right? (Édouard) Glissant talks about how there is no colonised person that can write In Search of Lost Time because your time did not follow European chronological time. Your time is discontinuous.

BO: How did you get to the point of interrogating who you are, perhaps decolonising yourself and getting to where you are now?

WU: I think for me it is a combination of many things. My mother’s famous phrase for me is “stop asking me stupid questions” since I was a kid. I have always had a natural curiosity on one side, and then, I think, exposure. Moving away from Nigeria – I went to an art university in the UK- opened me to a different way of thinking. And finally, being an artist. You are constantly trying to make sense of things. I think creativity is really about peeling layers off, reassembling and breaking. The regular world is about structure. It is about one plus one is two, but the world of creativity is imagination and saying what is possible or what is not possible or seeing what the limitations are and how we can turn this into an upside effect. I think it is a lot of that and definitely being a creative person. You cannot create or make honest work without having to interrogate.

EI: It is actually that I knew from when I was a kid that I wanted to be a writer and I consider that a real gift. It is not necessarily because of the fact that I can write but the fact that I had that clarity. The decision cast its shadow, in a sense, over everything I have done, all the decisions I have made. By the time I was thirteen or fourteen, I knew I just wanted to spend my life reading and writing, which is interesting because I remember the year after I left Law school, my dad and I were driving and he said to me, “So all you want to do in your life is read and write”. My dad had been supportive from the start but I think that was the moment for him that it became clear. Having that as a fact of my life from a very early age has been, I think, the most important way of being in the world. In some way, as far as I can remember, I have been either planning to write something or writing something. And when you are in that space, where you are figuring out, actually, you are being torn apart by either the possibilities or the limitations of language, I think that creates a sense of simply looking at the world from a different point of view.

BO: As writers within the art space, your work involves connecting the public with artists and their work. When you engage these artists, what are you looking for?

EI: This is probably simplistic but I just want to get to the place that the artists were when they were making the work. Because with a lot of criticism, sometimes it is boring, you know, especially as I have a literary background, I am always thinking, “Can I give back something?” You have put out these images in the world. How can my writing be a generous gesture?

BO: A complementary gesture?

EI: Complementary, yeah. How can the writing I do about your work exist on the same plane? This is audacious, of course. It is even scandalous because you are asking, how can you even paint that? How can you take that kind of photograph? How can you make that incredible piece of sculpture or make this installation? My mind cannot fathom it. It is the very fact of the mystery of the work of the artist that I am trying to get to and that’s for me, at this point, the most important way of approaching art.

BO: Would you say your work is not from the place of a critic? And if you are not a critic, what are you?

EI: Again, I am a writer. This is a very big question. I would like Wana to answer too. But, I will say here that I have found it very problematic accepting the designation of an art critic. There was a time that I deliberately put it in my bio, as a political point, but in my practice, I am not looking to make criticism. I am not an art historian. I don’t necessarily think about the work from the point of view of the work that has existed before it. Where does it fit within history? How does this cast a shadow on everything else that will come? I am thinking more about gaps.

WU: It is more about the individual than the individual’s work, right?

EI: Yeah! Also, I think like “That’s an incredible image, I can’t stop thinking about it”. It is something that has “entered my eye”. I said to some people recently that I am not interested in writing bad reviews. Why? All that energy, I will like to invest it in what I love.

BO: Is this sentiment coming from the fact that you two are also creators in a way?

WU: Yes.

EI: I think exactly because of that.

WU: This is why I am not a critic. I am really, genuinely interested in the process of creating and deconstructing that. What are the ideas, and how does this form? How does this morph? How does this evolve? How does this change? And what does it mean? It is something that holds so much history, so much process, but when it comes out, we just enjoy it in this very finite way. There is this finite way in which we enjoy it that people don’t know how much it embodies and I think I am very interested in expressing and uncovering what is important.

EI: You could call me a critic in so far as in the art world, I have artists as friends and write reviews for art publications, that’s fine. But I am not a critic in so far as I am not interested in being an expert.

WU: I am very interested in what you say about that. Did you ever at any moment feel, even in the baggage of the term ‘critic’, did you ever feel any way out of your depth? Because I like that you said you are not interested in being an expert and we know that criticism language involves knowledge of history and how that connects to now.

EI: Well, I think it will be facetious to say it didn’t bother me in some way. But I think that when it started bothering me I was kind of far along in my understanding of the kind of writing that I wanted to do. I will admit that when it began to matter, I already had started publishing in art publications. So, I came to a point of… maybe it is a point of bragging that, you know, it is not like I am not being approached to write something, maybe I can write this thing, maybe I can write about art. But I think that there is an even more important question which is every time you are writing a new piece, what kind of struggles do you have? For me, that’s more important than whether an art historian reads the piece and thinks that it is not good enough or whether someone reads it and says I don’t understand. What is important to me is how I can write and get to a place where I feel like, okay…

WU: …You are happy with the work.

EI: Well, maybe not happy because I don’t think I am ever happy with the piece I am writing.

WU: Well, nobody is ever happy.

BO: Perhaps, you have delivered what you can of that piece.

EI: Yeah, yeah! You’ve delivered it to the point where you feel there is some clarity about the ideas. For me, that is the most important matter. Then, of course, you can call me whatever you want and I also give people that right, that they can designate me. Call me a critic, call me a curator, call me a graphic designer, you know, (chuckles) let us start having a conversation from those designations.

BO: How is this for you, Wana?

WU: I think again, it goes back to talking about working in different mediums and what it does. I think when you are working in multiple things, it is always about a breakthrough and so different breakthroughs give you a certain kind of confidence and I find that makes you feel or helps you to start to define yourself. Because in a way it is a distraction, right? You are not bothered by what everybody else is projecting on you because you are doing all these other writings and you see breakthroughs in a very interesting area. Whether it is an essay that you’ve written or a piece of journalism or a film that you’ve made. You are occupied by that, so you are more interested in “how can I make more breakthroughs in the work I am creating?” as opposed to what everybody else thinks I should be creating or how things should be. How am I going to create more compelling work? So yeah, maybe it is not about being happy with the work I am creating but how I can constantly push my own internal barometer.

BO: Let’s talk about the arts in Nigeria.

WU: I will come to it from all perspectives. From theatre to visual arts, music, literature. I have moments where I think it is boring.

BO: A sum of all the arts?

WU and EI: A sum of all the encounters!

You will be the luckiest human being if the person closest to you is not demanding a material indicator of success in Nigeria.

WU: I have moments where I find it boring because I feel artists are not really engaging issues or concepts or ideas to create and I think we are experiencing a moment where art is now a trend. Art is having its cool moment and we are having what I call microwave work, let us just do it “sharp, sharp”.

EI: Hyperrealism.

WU: Yeah, hyperrealism! This technique is hot right now but we are not thinking about the subject matter. Around the world, there is experimentation happening. There are people trying out interesting things. So, I am wondering how much the artists are focused on the audience when they are creating and how that affects their work.

BO: Isn’t that a question of what kind of audience?

WU: Or the assumed audience. In terms of original interest in compelling work, there are not as many as I would like to see or experience.

BO: Why do you think this is so?

WU: There are many factors. There is the factor of the art educational system which does not give room for experimentation or does not open young people’s minds enough. Our general educational system – as you cannot extract the art educational system only – is about ‘study and regurgitate’. Critical thinking is not exactly a part of teaching methods. For you to break out of that, there is a lot of work you have to do on your own. The educational system has raised you from when you are zero years of age to when you are twenty-two or twenty-three years. It takes a lot of self-interrogation to be able to move out of that to create certain kinds of work. Then, of course, money and hunger are factors. People want to be able to create work that will supposedly sell. There are a lot of things and it is not necessarily that artists are just lazy. I think it is very important that we confront the structural and systemic issues that stop artists from being able to express themselves the way they would fully like to.

EI: The question is what I think about Nigerian art in general. I think much of it is still rudimentary. We are still starting out. When you think about the fact that Nigeria’s literary industry is still developing, like, it is still so new. It has been new for a very long time, by the way – 50 years – but it is still so infantile that the only way to gain a certain level of recognition and acknowledgement for your work is to be published outside the country. Nobody can debate that. You are a writer and you can’t imagine a way forward for yourself, in a significant, scaled-up manner except you leave the country. And I am talking across board. You have some people who are skilled but have not interrogated themselves in the practice, and that is being celebrated. You also have a system where the more followers you have on social media, the more it is possible. There are few exceptions, and I don’t want to put numbers or call names, but they are few. The more followers you have on social media, the more it is possible for you to create some kind of work and say my work is this or that. In my thinking, I am very dedicated to not being an expert. We have to start from a different point of departure – which is, how do we deal with the very basic questions in the mainstream? Not only when we come together at a fair. I am interested in writing what can address any form of intelligence. And I am not saying that a child that is five or twelve can understand my work. That is facetious. But an engagement with a person who is not used to entering the gallery is important. Because we are not there yet. We are not even where the market, as they say, is segmented enough to know that. We don’t even have a museum.

WU: I feel like form and content are not intersecting yet. People have learnt the technique to know how to paint but that is about it. I am also wondering again about our culture because as much as we are talking about art, I feel like it filters into everything else. We don’t have a culture that allows you to have a voice. I wonder how much of that filters into art. So again, you have a skill, you can paint but what do you want to say? How do you know how to say it? I see a lot of works and they do not say anything to me.

EI: Well, the very nature of the Nigerian society is almost anti-intellectual, so once you start writing in a way or talking in a way – and you probably know this better than I do – once you start sounding intelligent, the first thing that people will notice is that you are speaking big grammar.

BO: But isn’t the essence of growth to advance from one point to another?

EI: Absolutely! But you have a system that constantly tells you that you have to be simplistic and simple-minded. Of course, you also have a system that makes it clear to you from the very start that if you don’t have a material indicator of success, then, you are just wasting your time.

WU: Exactly. People will ask, where is the money?

EI: And I am talking about from the most intimate of your spaces. You will be the luckiest human being if the person closest to you is not demanding a material indicator of success in Nigeria.

WU: I have questions for Emma. Are there things you experience, things you know but you feel you can’t share with other people because they don’t get it? Do you ever feel that way?

EI: Yeah. One of the first questions my brother asked because I travelled a lot, was, “Bros, are they paying you?” I think this is what makes it even more urgent to do the work I do and to clarify my intentions. Not so that I will reduce the complexity of my work but to present it in such a manner that if you are willing to engage with the work, there is something there for you.

WU: Do people like that make you feel an obligation to be visible?

EI: Well, actually at some point. I used to tell friends that I court obscurity because I have this neurotic thing about photographs. I don’t like photographs of myself. But it occurred to me that it is almost inescapable.

WU: Because you have to normalise intellectualism, right?

EI: Absolutely. You have to be able to say for instance that I will put up this kind of photograph and this kind of caption on Instagram and not care whether it is what people put up on Instagram.

WU: I feel that way as well. There are certain things on a normal day I don’t really care about, but sometimes, I feel I have to normalise it because success looks like different things. People who are coming up after you who might be interested in this kind of thing should know that there are people that live, survive and thrive doing this.

EI: When I went away for my Masters in 2013, nobody had ever heard of the course I was going to do. What does that mean? Are you training to be an artist or what? But it is really – and I say that with all sense of modesty – an indicator of some kind of success that 5 years later, someone is thinking of doing that program, because for five years, as a result of that education, I have been writing in a consistent manner about art. I am not scared about that kind of visibility that is beyond me or that is, in a sense, a gesture towards others. The kind of visibility that appals me is one that must be commodified, that you have to indicate your success by how many views you have on each video. But what does it mean for someone to say ten years from now, I am going to do a series of films on trauma because Wana did it? That for me is the most important thing.

EI: I have one question for Wana. I think we have talked about it briefly. One of the big, existential questions for me now is one of aspiration. How do you define for yourself what success is, or what success could be?

WU: It is a very good question. I constantly think about this and it is really something that shifts, and it needs to always shift if I am going to grow. But I place most of it on the work. I remember at a point, success was just being able to do the work. It felt impossible to do certain things. The realisation of achieving something I thought of as impossible was, at a point, my definition of success. Later on, I had moments where it conflicted between the number of eyes I had on it and the engagement that I got from it. For instance, with visual work, you make something and it is only 500 views, and, you conclude in your mind that this clearly is not successful. But then you receive 10 emails from people literally crying, you can see the tears in the emails, or people tell you about their whole lives in emails and that gets you astonished.

So, I think as I am growing. It is a combination of a few things which are not just being able to do the work anymore but to be able to do it well and to be able to make it compelling. Then, connectivity is very important to me. I think there is a case for inaccessibility which is fine but I find that connectivity is important to me and I think that is because my art didn’t come from what I was exposed to. It came from an organic place of needing to express events in my own life. I tell people that art saved me. Whether it was writing, or poetry. In fact, it was poetry that saved me, literally. I don’t know if I would still be here. Art came from a very organic place of needing help and an outlet. It amazed me that this thing could make me feel whole or piece me together again. And so, the success of most things for me is being able to connect. It is really about the core of human emotion or the human condition.

BO: Thank you so much for your time Wana and Emmanuel. But, one last question. How do you see and how do you internalise the things you see?

EI: Well, my short answer is that I have a lot of faith in experience. I also have a lot of faith in the crack between recollection and reflection, in what I remember and how I process that. I will also include prophecy, because, well, I am a minor prophet.

WU: How do I see, interpret and deconstruct? I consume with an openness. I try to remove my own personal ideological biases. It is freedom to be able to take things in with an openness, especially, living in Lagos where one’s mind is rolling like a speedball all the time. So, I will say I process through memory, interrogation and reflection.