For its opening exhibition, the new art space, Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Tamale, Ghana, chose to celebrate the life and work of Ghanaian modernist artist Galle Winston Kofi Dawson. Why would a contemporary art space choose a modernist artist for its inaugural exhibition?

![Kofi Dawson, Ants [3rd edition], (2018), groundnut shells, copper wire, dye, and sawdust. Courtesy Nii Odzenma for SCCA Tamale Kofi Dawson, Ants [3rd edition], (2018), groundnut shells, copper wire, dye, and sawdust. Courtesy Nii Odzenma for SCCA Tamale](https://thesoleadventurer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ants.jpg)

A few minutes to the official opening of the retrospective exhibition, “Galle Winston Kofi Dawson: In Pursuit of Something ‘Beautiful’, Perhaps…”, at the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Tamale, the artist, Galle Winston Kofi Dawson born in 1940, inspected his mounted works with a familiar, yet, intense gaze. Asked how he came to be an artist, Dawson recalled seeing what he presumes to be a diamond when he was a child. As quoted in the curatorial statement, he says, “I’ve always been trying to find something that would remind me of that beautiful, colourful diamond (that) I saw…” This seems to be what draws him to art that is rooted in experimentation, exploring what his mind leads him to, and politicising the personal. A product, perhaps, of his penetrating gaze.

Spanning over sixty years, his body of works include drawings, paintings, prints, objects, and texts. His paintings, largely untitled and undated, cut across portraiture, everyday life, religious subjects, and landscape. Using vivid colours, Dawson evokes emotion rather than realism by sometimes exaggerating body parts, breaking away from the traditional Akan aesthetics, as is evident in his drawings of the human figure. In his book, Ghana’s Heritage of Culture (1963), Kofi Antubam, a pioneer Ghanaian modernist, writes on the Akan beauty aesthetic and illustrates figures with egg-like head and neck combination, necks adorned with rings, and slender limbs. This representation of the human figure is akin to what is commonly referred to as the ‘Coca-Cola shape’. Although the neck ring is an anatomical anomaly, it is viewed as an Akan beauty aesthetic. Dawson, however, extends the rings all over the lower limbs, distorting the Coca-Cola shape.

Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys (1998 – 2014) reveal that the prevalence of overweight and obesity issues have consistently grown over the years, showing an increased body mass index (BMI) of Ghanaian adults. If the average Ghanaian is getting bigger, how then do we label beauty? How do you speak to the ideal of beauty in the face of changing body sizes? And, more importantly, is body size the marker for beauty? Dawson’s offering is expansive in admission, defying the ideals that Antubam espouses.

In his everyday life paintings, Dawson sticks with the Ghanaian modernist ethos of adapting daily Ghanaian life to the canvass. He also rejects the conventions of traditional three-dimensional representation while clearly depicting well-formed bodies. One of such paintings portrays a scenery of Nima, an Accra neighbourhood where Dawson has lived for a long time. In the painting, two women lie on separate benches, arranging themselves beside each other, one on her back and the other on her side. A third woman kneels close to them with her hands wrapped around her head. Across them, another woman stretches a plate in the direction of the three women, none of whom notice the gesture. A man sits between the two groups of women, eating kenkey. Away from the group, on the left, a woman in hijab sits. There is an armoured car in the background.

Nima is a multi-ethnic and multi-religious community. The geography of Accra, the capital city of Ghana, is such that unofficial settlements spring up in and around official ones. Nima is both an informal and formal settlement. It is home to many skilled workers who work in and outside the community. Skilled workers who might have to contend with the seasonal availability of work and wages. The painting captures the hustle of the community. While it may appear like there is little to no state presence – in terms of welfare – in the community, Nima sits just behind Jubilee House, Ghana’s presidential palace. The armoured car in the background seems to be a metaphor for the government’s presence. As if we ought to think about the distance between that group of people and the armoured car as close in distance, yet, far away in functionality.

In Trotro Experience painted in 2018, Dawson squeezes human figures to the side of a silkscreen printing showing a scene from a trotro – the shared mini-bus common in Ghana. Two women– one with a baby on her lap, and the other sleeping on her wares – sit with the head of a man, presumably the driver, in the background. A hand stretches in between the women, towards the man.

Both paintings are also examples of Dawson’s work termed ‘Afro-journalism’.

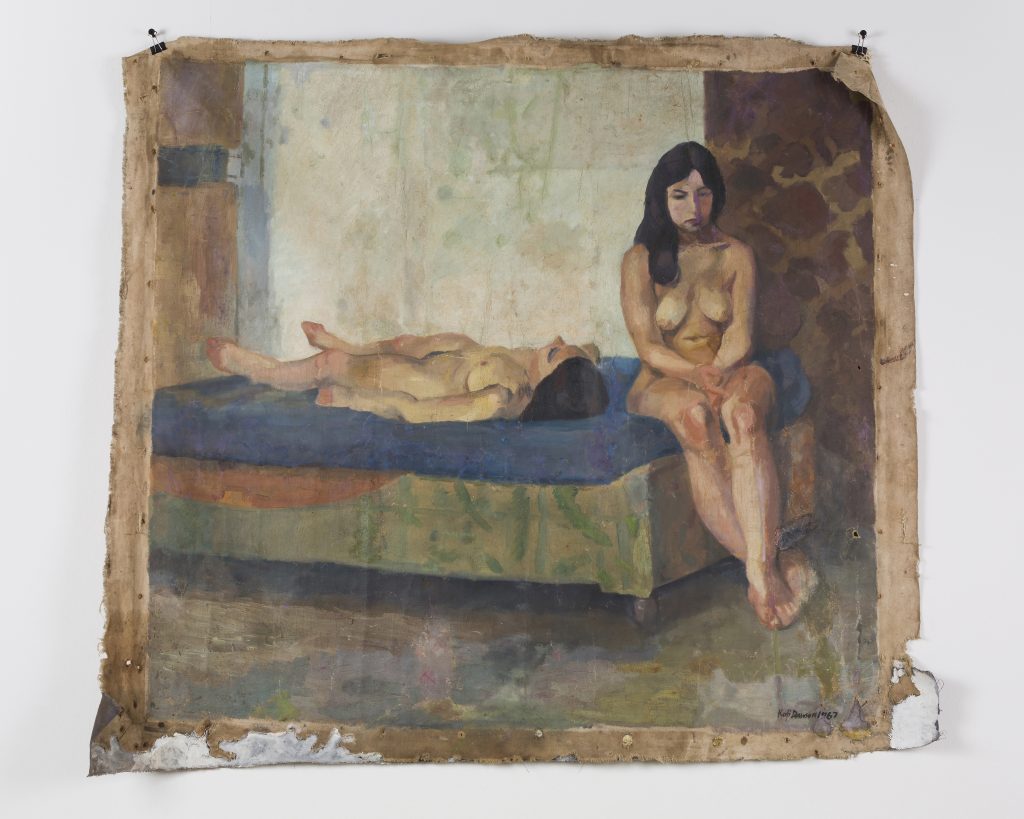

Dawson’s earlier paintings dated 1966 and 1967 feature two nude Caucasian women. In the former, one woman lies on a bed while the other woman sits on a chair with her head turned away. But in the 1967 painting, the woman formally sitting on the chair is sitting on the edge of the bed in the same posture. It is as if the two women are sharing a moment of silence, intimacy, and vulnerability without being sexual.

The Caucasian body could be an indication of the gaze from which Dawson operated earlier in his career. As one of the first to complete the BA Art programme at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, and later, the Slade School of Fine Art, his education was deeply Eurocentric. But like others who came after him at KNUST, El Anatsui most popular among them, their education turned personal, leading to incorporating objects found in their local environment into their works.

Midwifery (1996 – 2018) is an ink drawing of a scene from a maternity ward. A woman is breastfeeding her infant. The midwife has her head done with plantain peels. In Market Queen (2003), a found object (fabric) sits on the acrylic painted head wrap of the market queen. Together, they combine as an elaborate head wrap. In these pieces, Dawson’s modernist formal education and his contemporaneous self-education come together. What you find is a combination of formalist and experimental approaches.

Dawson’s artistic output is an act of resistance. Although trained as a modernist artist, he branches out to contemporary art forms.

At the heart of Dawson’s art is improvisation or experimentation, as it were. Jelly Fish Lamp from 2011 is an installation made from split plastic bottles shaped to look like electric bulbs which are attached to other found objects. They are arranged in such a way that when they hang, they look like traffic lights at the intersection of two adjoining highways. In addition to the various installations he has produced from wood, bottles, plastic, and sawdust, the exhibition space is also littered with installations of ‘ants’. He explains that he had a “miraculous visitation” from an army of ants and has tried to replicate what he saw. Made from groundnut shells and electric copper wires, the ants crawl on the floor and on top of walls. Other installations are painting tools that Dawson made at a time that brushes were scarce in Ghana. He attaches goat hair and electric wires to kebab sticks, some of which are now split open. Over the years, he mastered the art of using these tools even as economic normalcy returned.

Accompanying the retrospective are notebooks carrying Dawson’s texts. He says he has kept a diary since he was forty to compensate for his lack of writing. The texts come from his everyday life, dreams, and meetings. They offer a window into the mind of the artist.

Dawson’s artistic output is an act of resistance. Although trained as a modernist artist, he branches out to contemporary art forms. This could shed light on why a contemporary art space would choose a modernist artist for its inaugural exhibition. The Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) is more than a gallery space. It is also a research hub, a cultural repository and a residency centre for artists established by renowned artist, Ibrahim Mahama, to give visibility to contemporary art practice from northern Ghana. Despite largely producing on his own and without institutional support, Dawson has been devoted to his work, following his mind, which has led to bold results that challenge his formal education. To be able to see his retrospective is, undoubtedly, a moment of grace.

In Pursuit of Something ‘Beautiful’, Perhaps… is open until August 15, 2019.