If we were to live in a world without labels, would we become more tolerant of one another? For instance, a world where there are no norms or deviance, identities are not pre-constructed, race does not exist, and individual differences are recognized as what makes us human. Would this world be anarchic or dynamic?

This is a complex rhetoric and one of which the answer was already given. Labelling and classification are how the world knows how to exist. They are schemes, institutions and mechanisms of control. “Classification schemes are now understood as necessary to both survival and intelligence, and human beings may be hardwired to make categorical distinctions,” john a. powell and Stephen Menedian wrote in The Problem of Othering: Towards Inclusiveness and Belonging. Also, “Scholars have long observed a tendency within human societies to organize and collectively define themselves along dimensions of difference and sameness,” they added. However, these same tools and mechanisms that are designed to organize and create functional societies simultaneously produce oppression, exclusion and marginalization, through alienation and othering. For when there is one, there will be the other. Where there is a majority, there will be a minority. As long as classification exists, there will be groups on the fringes of human societies.

Even as the world is progressing, and these days inclusiveness is a keyword in political, economic and social discourses, othering and exclusion remain a problem. In news reports, as well as in movies too, more emphasis is laid on our differences than similarities. “A gay black woman”, “a straight white man”, “a Muslim terrorist”, “an illegal migrant”, and so on are common descriptors that precede actions or persons in the news. Reactions are thus manipulated or influenced by pre-existing meanings and emotions associated with these descriptors.

Labelling and alienation manifest in different ways, but very prominent are religion, race, ethnicity, gender, appearance, sexual orientation, social and economic class, and politics. While these classifications are not necessarily in themselves dangerous, they often lead to bigotry. Particularly of those who do not belong to the dominant groups. It is in the context of these systems and structures of alienation, control and entitlement that some of the works in the exhibition “Four Women” are presented.

The exhibition, a group show of women artists with works visibly tied to the subject of gender features Adejoke Tugbiyele, Kehinde Awofeso, Olubunmi Oyesanya Ayaoge, and Stacey Okparavero (Ravvero). The expressions in their work range from constructions of identity, non-conformity, otherness, alienation, and self-awareness to expressions of resistance and reformation, framed within the structures of patriarchal and cultural traditions.

Tugbiyele, a queer black woman, and one who openly embraces this label has for many years addressed topics of sexual politics, identity, oppression and marginalization, through the dynamics of gender, race, religion, and class. She embodies these labels to be true to her ‘authentic self’ and as multiple windows of being. Worth mentioning is that Tugbiyele is of Nigerian descent, an African living in America, and was raised as a devout Christian. According to Glenn Adamson, a contributor at Crafts Council magazine, UK, Tugbiyele “happens to fit into nearly every category currently facing oppression, (in America)”. I dare say, if she were to be in Nigeria, her circumstance would not have been any better. Yet, instead of being resentful towards the world, she confronts oppression with love, open heart, tolerance, and compassion.

In Four Women, Tugbiyele presents two recent works: Shifting the Waves and Queen and Her Throne, extracted from her project “My Queen’s Throne”. The former, a video and performance piece set in the courtyard of Somerset House in London, weaves colonial narratives, personal story of love and racial experiences with spirituality, and the later, a series of photographs characterize the love shared between two Black women. It was developed in collaboration with Sisipho Mandy Ndzuzo, vocalist and dancer from South Africa. Although set in the context of personal love and affection, Tugbiyele explains: “Queen and Her Throne simultaneously call for self-awareness, and questions the place of women in society today against historical and ideological setbacks which have created roadblocks both physical and spiritual in nature.”

In the conceptual framing of Shifting the Waves, healing, transformation and equality are key components. There is the presence of water, that is River Thames, which becomes a life force, a passage for transformation and liberation from systems of persecution and prejudices. Symbolic materials such as mask, brooms, boat and sound box, used within the performance, embody the historical, physical and spiritual. For instance, in African societies, the broom is a ritualized object having spiritual, socio-religious and environmental references that point toward cleaning dirt, evil and negative energies. In similar belief, Tugbiyele uses the silver painted brooms, titled Same Sex 2.0, to cool the atmosphere and conflicting energies within the vicinity of the performance. The history of the space and some of the buildings around Somerset House were equally important. They bring back memories of the socio-economic activities between Africa and the West during the colonial era, and how this shapes the African economy and lives today.

Within these connected ideas and complexities on identity, economics, spirituality, and marginalization, the intention, for Tugbiyele, remains to “inspire new rituals that inform our need for greater self-awareness, grounding, and empowerment within the healthier shrines we build that celebrate our authentic selves.”

Also following the path of the authentic self is Awofeso. Younger than Tugbiyele, she identifies as ‘gender non-conforming’ but adopts the feminine pronoun ‘she’, especially in the context of the exhibition. By general perception, she ‘appears’ masculine, has a voice and mannerism that suggests a male being but has the biological sex of the female gender. She is caught in the reality of living in a society lacking in empathy and tolerance for the uncommon. Fear and uncertainty accompany her presence in public spaces, especially in Ibadan, the third populous city in Nigeria, where it no longer feels like home. She is pressured to seek for safety and perhaps, acceptance in a city more diverse like Lagos. Although, Lagos is not without its prejudice and discrimination of sexual and gender differences.

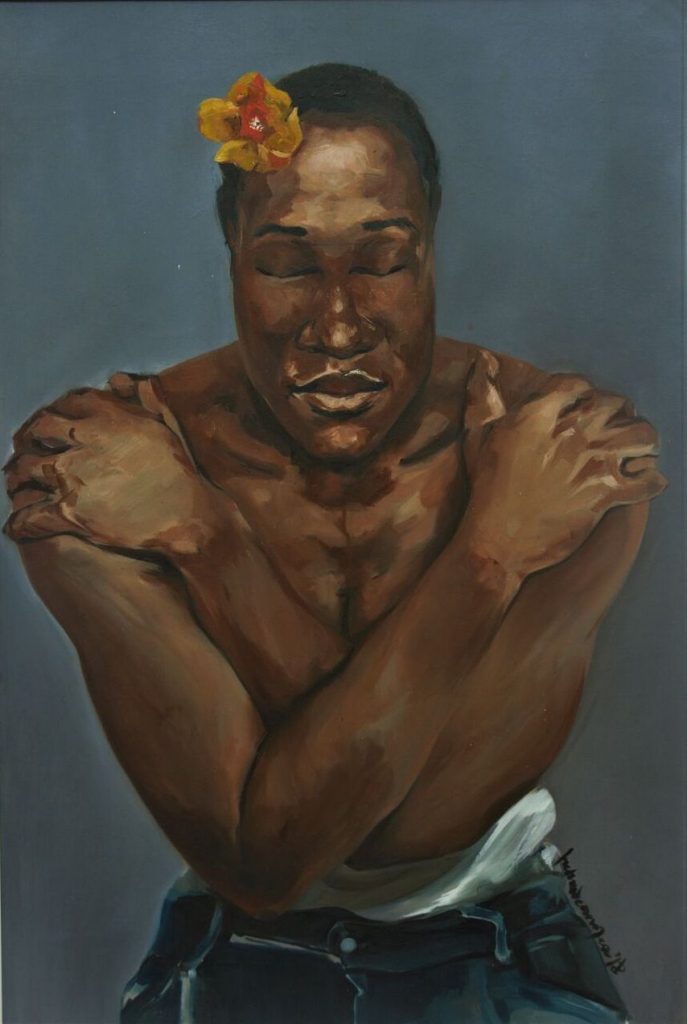

With five delicate self-portraits inviting public gaze, Awofeso confronts the observer with the multiple possibilities of gender and personhood. The portraits, titled Questioned to Shame, Undaunted, Kilode, Silence and Self Love, suggest a body familiar with bodily subversion and unpleasant scrutiny. In one portrait, her face is raised in question unperturbed, while in another, her back is exhibited in submission for analysis. A happy escape in the disturbing array is Self Love, a portrait of peace and self-acceptance. In these paintings, it is unclear whether the exhibition of self is voluntary or forced, but, for someone who has been subjected to “hostility, shaming, verbal abuse and confrontations”, as she says, it is apparent she wants the spectator to see who she is and simultaneously be aware it “poses no harm to them or the society”.

Although “Four Women” manifests as an exhibition about identity, navigating patriarchal systems and taking up an agency, challenging prejudice is at its core. Looking at the struggles Awofeso faces, one wonders why societies, particularly traditionalist ones like Nigeria, are threatened by the unfamiliar and push back against non-conformity.

The other artists in the exhibition present additional subtleties on identity. Ravvero, clearly a young woman eager to make her mark in the art world, addresses identity within the constructs of profession, nationality, and race. In We the Kings, artists become kings and leaders adorned in crowns and royal attire. In her words: “the artist is central to the art ecosystem and must know the responsibility and power that comes with the role. They must know they are kings and not pawns.” This, she says, applies to ‘being Nigerian’ and ‘being black’ in the world today. Unlike artists who accept gender as part of the agency of their practice, Ravvero has decided to separate her gender from her profession. She addresses an artist as a ‘being’ and a leader as non-gender. However, she is not ignorant of the biases and obstacles of being a woman as she has demonstrated in a previous project titled “Feminism isn’t a dirty word”.

Ayaoge, well beyond an emerging or new artist, delves into the world of gender roles and inequality. Through the lens of stereotypes and traditional expectations of women, she presents the female being. What does it mean to be female or a woman in Nigeria, a highly male-centric society? The girl child is still married off at an early age in most regions in Nigeria, birthing campaigns and hashtags such as “Child, not bride” in recent years. Despite the campaigns, there is yet to be a legal act protecting the girl child from an early marriage as shown in Ayaoge’s Child Bride Bill Procrastination. The girl child is still the target of abduction by insurgents in northern Nigeria. Access to education is low and often a secondary priority compared to the male child. As an adult, the woman is expected to assume domesticated roles of ‘wife’, ‘mother’, and so on regardless of any professional achievement. Her role in life is pre-determined and shaped by ignorance. Though there has been some progress in the opportunities women can have within societies in the twenty-first century, actions are still needed to drive equal opportunities between women and men in socio-cultural, political and economic areas.

In the context of gender inequality, “Four Women” also examines the visibility and representation of female artists in Nigeria. As in most regions, the Nigeria art scene is male-dominated. But, this does not mean females are non-existent. Looking at the history of postcolonial modernism in Nigeria, it is evident who history favours. While names such as Ben Enwonwu, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Uche Okeke, Ben Osawe, and Yusuf Grillo, are constantly represented and documented, their female contemporaries are barely known. Until recent endeavours by curators and female artists, many were unaware of the postcolonial modern artists Colette Omogbai and Clara Ugbogaga-Ngu. Even the familiar name Afie Ekong has enjoyed little recognition for her contributions to the development of the early art scene.

This is not so different in contemporary times. Female artists are still confronted with visibility and documentation problems. The irony of this situation is that in the last two decades, there have been many prominent women that have championed the arts in Nigeria. So, the question is how are they shifting the visibility and representation of females in the arts? A number of them are excellent facilitators that are making tremendous efforts to change the narrative. They are pushing female artists forward, exhibiting their works, and spreading the word through publications and social media. These recent activities have ushered in some significant progress, but, the challenges and biases of the female artist persist.

Four Women: Resisting Prejudice and Inequality was originally featured in the publication by Revolving Art Incubator on the exhibition Four Women.