“Set out, explore every coast, and seek this city,” the Khan says to Marco. “Then come back and tell me if my dream corresponds to reality.”

“Forgive me, my lord, there is no doubt that sooner or later I shall set sail from that dock,” says Marco, “but I shall not come back to tell you about it. The city exists and it has a simple secret: it knows only departures, not returns.”

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities.

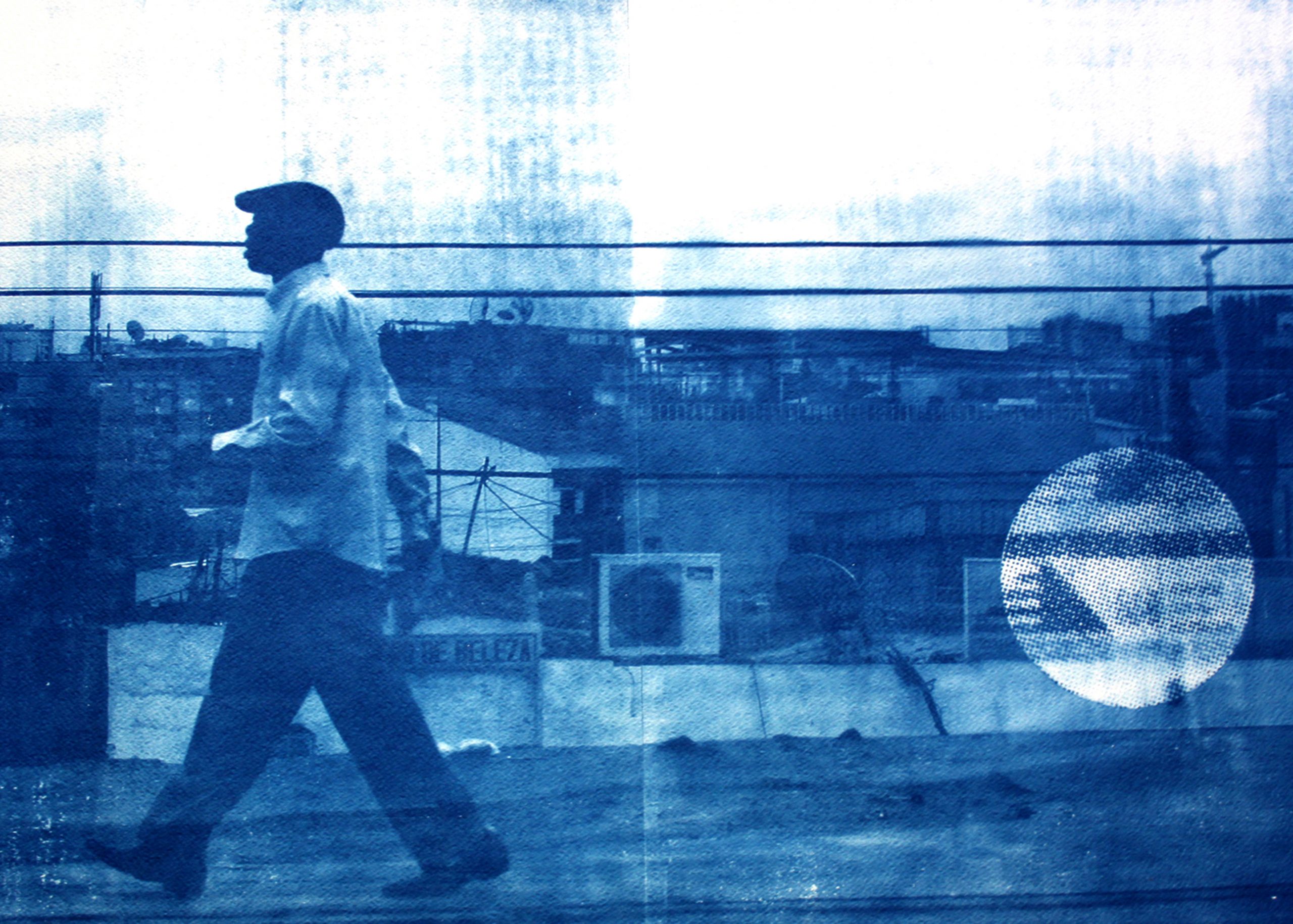

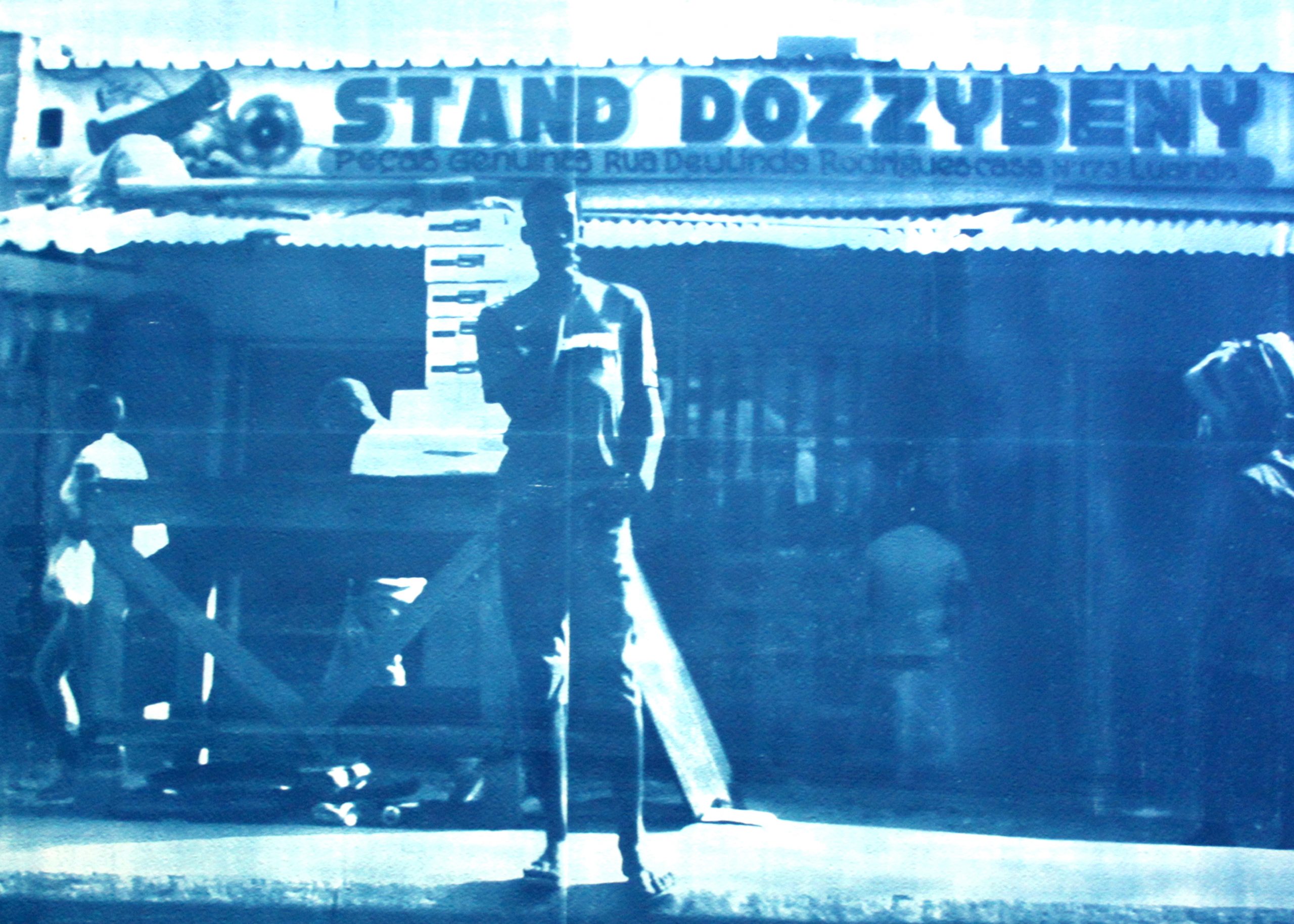

At first glance, Délio Jasse’s images of Luanda in Terreno Ocupado come to us with the hazy nondescriptness of old postcards or newspaper clippings. Save for the fact that each photo is cast in the blue tinge of cyanotype print, the only thematic consideration seems to be that of a documentarian’s realism. A level realism in need of nothing more than the basics. Easy weather, light, and a good vantage from which the eye can roam. The eye of the photographer seems neither trained nor amateurish, neither disinterested nor voyeuristic. The city is both everywhere—open, accepting—and nowhere—elusive, indistinct. What the eye reveals to us it reveals willingly, but without further invitation. It looks but does not say what it looks at, as if unsure of its role as guide or interpreter.

Born in Luanda, Jasse left for Portugal in the final years of Angola’s bitter civil war. He returned a decade later, lured by ‘a nostalgic feeling,’ and ‘a plain and simple curiosity to see what had happened across the city during such an important time.’ Hence, we are not simply looking through the eye of a typical stranger but of a stranger whose strangeness is not total, or definite . The condition of the stranger is a perplexing one, for it is one made legible by illegibility. The stranger appears obvious because he cannot tell what is obvious. We know he is here because he is not of here. But perhaps even more perplexing is the condition of the stranger who was not always a stranger but becomes one in the protracted process of return. ‘To flee,’ Mia Couto writes, ‘is to die from a place’.

Having now lived a year and some months in the city in which I became an adolescent, I understand the terrible fragility of this ‘second life’. The streets I thought I knew sometimes appear as they always were, but on other days, I find myself wondering if indeed I ever walked them as a boy. Time, also, is inverted. I know chronologically that at least a decade has passed, yet in embodied time that interval some days feels much longer, almost like another life. And on others, I enter seamlessly into the memory of cool, aimless Saturdays, the smallest details bright and clear in my mind. These disorientations inspire wonder. It is impossible not to appreciate in some way one’s endurance, and the endurance of other things, like the store where the elderly man still makes earnest jokes and asks me where I’ve been, or the old creak of a door which now seems louder than ever. But there is also grief. The grief of looking into old mirrors and noticing, for the first time, the weathered brow, the paleness of the eyes. The grief of standing where some younger self stood, with the awareness that more has changed than one could ever know. The grief that things go on.

It is perhaps this unsettled experience which Jasse also carries with him as he looks upon the city which was once his home. As the perspectives of adolescence are stretched into new dimensions, made to bear new and perhaps harsher lights, Jasse is forced to look at everything twice. First, through the lens of memory, and then with an outsider’s curiosity. What we see in Terreno Ocupado is an attempt to make room for the possibilities and inconsistencies of each. The tonal reserve we sense at first is not the result of disaffection but of a viewpoint in continuous inversion. The ‘second life’ of the returnee, Jasse demonstrates, is not only worthy of sustained interrogation, it may also offer compelling ways of seeing. For in apprehending ‘the idea of the city which had changed over time,’ one confronts one’s position relative to that idea. The work of looking closely becomes necessary as a means to examine one’s claim upon a place and the claim of a place upon one. A year of lockdowns may provide further motivation to take up this work. We have been, many of us, absent from the places to which we feel we owe something, to which we feel some form of belonging. And in our urge to get back into the open, to be again in movement, I wonder if we fail to take note of how those places are also moving. Surrendering, as they always have, to our carelessness and to time’s subtler incursions. Perhaps there is a need, quite simply, to stop and look.