In her recent work Born Throw Way!, photographer and visual artist Adéọla Ọlágúnjú interrogates the expression born throw way used to describe social rejects, discarded people, or people thought of as being of little importance. The project was created from extensive interaction with the area boys around the Opebi-Ikeja area of Lagos, Nigeria. She explores what it means to be an area boy, how area boys fit into the culture of Lagos, and how they are perceived in that culture. Speaking of her vision for the project, she said, “I wanted to photograph these people how they wished to be photographed.”

Born Throw Way! was selected in 2020 by Forecast, an interdisciplinary platform offering young artists and creative thinkers around the world an opportunity to work with accomplished mentors who can help them advance their ideas and projects.

In this conversation, writer Joseph Omoh Ndukwu discusses the project and the presentation at Forecast Digital Festival with Adéọla Ọlágúnjú for TSA Art Magazine.

Thank you for taking the time to have this conversation with me, Adéọla. Last year, Forecast selected you for a mentorship program, and your project Born Throw Way! was nominated in the category Still Images, Loud Voices. What inspired the project, and when did it start?

Although I wouldn’t describe myself as a documentary photographer, I have always had a certain interest in looking at the city, looking at spaces, looking at people, and looking at all of these intimately. As a person, area boys have always interested me. And not necessarily because they are scary or annoying. As an artist who has to go around in a city like Lagos, trying to make work, I am affected. These are people you have to deal with when you take a camera into a public space. However, there was a stronger, more important motivation. I wanted to move beyond my own prejudices and the general societal assumptions to really understand: Who is an area boy? I wanted to understand the culture surrounding area boys. I wanted to allow myself the creative liberty to wonder, to find out if an area boy thinks he’s an area boy or if it is just a societal projection? I wanted to see area boys as they saw themselves and photograph them as they would love to be photographed.

So, when I came across Forecast, I knew immediately what I wanted to work on and sent them a proposal. I included the title Born Throw Way! in the proposal; it came to me almost instantly. It seemed very much that I had always had the title with me even before I applied for the project. The proposal got accepted and I began work in March 2020, as I was in Nigeria during the COVID-19 nationwide lockdown. I took the opportunity to know the “boys” in the neighbourhood I was staying.

How did you get these men, mostly considered unruly and complex, to be at ease with you and to trust you?

Time did a lot of the work for me. I was not in a hurry. It was not a project I wanted to do in two weeks and leave. I stayed with them, sometimes not taking pictures. I sat with them under the bridge and in the areas where they hung out, just getting to know them. I think this made it easy for me to photograph them honestly.

It wasn’t pleasant all the time. The “I run this place, I am strong and powerful” thing was a continuous dance that sometimes got overwhelming.

In the Forecast program, the photographer Tobias Zielony was your mentor. He is known for photographing vulnerable and ‘unseen’ people on the fringe of society. Considering your interests are similar, what professional and artistic insights did you gain from your exchange with him? Also, what did you gain from the mentorship generally?

We were three finalists who worked with Tobias. We all worked together and got responses on our work from one another. So, it was mutually beneficial for all of us, mentor and mentees. Another wonderful thing that happened with the mentorship was the opportunity to have people from a different cultural context look at the work, relate to it and make their own responses. Having the work transcend borders in this way was truly beautiful.

In a video for Forecast, you said that it is important to you that people are seen, and you want these area boys to be seen. You also said you wanted to examine questions such as, “What is the psychological space of a person living on the edge of society? And how is the struggle of being and becoming reflected in the performance of one’s daily life?” These goals are both noble and ambitious. I can’t help wondering, though, if there is a bigger goal. Did you hope that people will be more accepting or forgiving of these men and the indignities they subject people to?

I wouldn’t say there was a specific “larger goal”. I really just wanted to do the work because I found it interesting. It was also a way of looking at myself because really, it doesn’t matter what I photograph; I see everything as a kind of self-portraiture. I also wanted to understand the place or position people occupy in society. I am interested in why people don’t belong in a society in the fullest sense and are only needed to perform certain functions. These so-called area boys, for example, are busy during elections because they are hired to fight or become political thugs. But, they are hardly ever invited to oga’s birthday party or other special events because they are not needed—and do not fit—in that setting. I wanted to understand this utilitarian dynamic by observing how it works and listening to their personal experiences. Additionally, I wanted to look into the power structure that sustains the area boy.

What do you mean by power structure? Do you mean a hierarchical structure?

Yes. The hierarchy between the area boys themselves, the hierarchy between them and myself, and the hierarchy between them and the city. They know that they have a certain power. They are aware they can be called on to make things either go wrong or make things better or peaceful in the city. They also feed off the anxiety or fear of an average person living in the city. That is some kind of power.

In the series, I find that you seem to be very concerned with banality and ordinary people’s daily struggles. This makes me think of your other works, particularly the series Beautiful Decay in which you photographed decaying things, waste, murky water, oil spills, and the like. Also, I am thinking of two other projects: A Day in the Life of Henry and Paths and Patterns, which, although different in approach, centre ordinary people trying to eke out a living. What’s the fascination with earthy things, with banality, and with the lives of ordinary people?

I wish I could articulate the answer in a language that fits into academia or the language of the art world. But, I think it is something that comes to me naturally. Why do we find it hard to explain why we like the things we do. It is about taste; it is about preference and curiosities. I need to have an in-depth understanding of things that interest me. And I am interested in people, especially in the people society has pushed to the border or the edge, people we refer to as prostitutes, hoodlums, born throw way, area boys and the likes. And so—although I don’t know how it works—I discover that people sense this desire in me to really know them and are willing to open up themselves to me and share their stories with me.

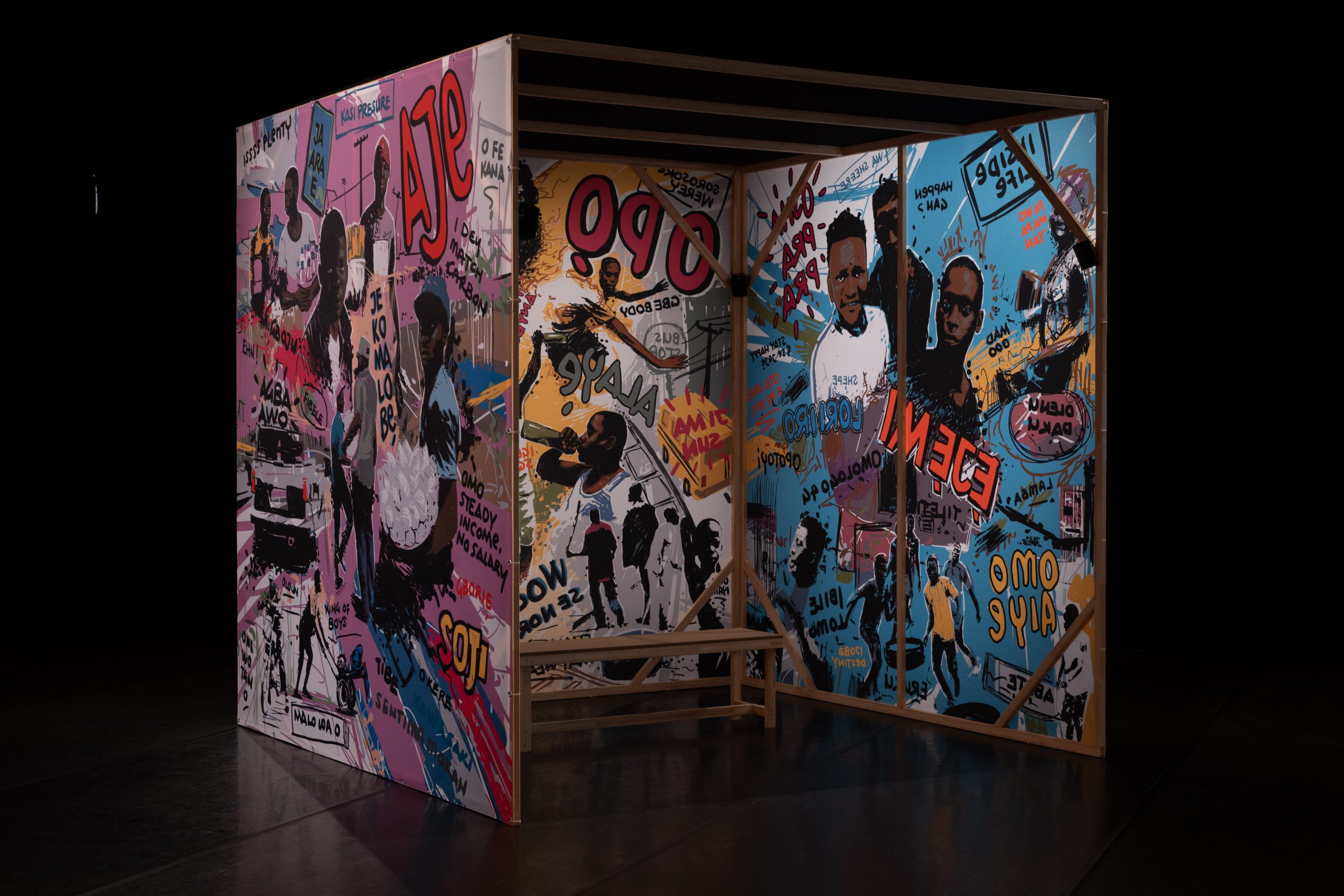

Let’s talk about the presentation at the 5th Edition of Forecast Festival, which was online. The immersive installation included photography, text, illustration and sound, bringing these young men alive in dimensions that differ from those of still images. Did you find it crucial to give them a voice and compel society to hear them, especially as you insert their voice and expressions into places they would ordinarily not have access?

To say I gave these men a voice could be likened to the heresy of the white man (Mungo Park) discovering the River Niger. I mean, how do you discover a river where people have lived and occupied for aeons? These men have a voice and what they say is everywhere. It is woven into the social and cultural fabric of Nigeria. What I did was to listen to it and acknowledge it without trying to impose my own “sense” upon it. I let it exist in its own right. To pay attention, not to censor or “clean up” what they say or how they said it was a choice I made to maintain the agency of these people.

Putting these voices in different spaces and contexts invite or allow society not only to hear them but to hear them as themselves, with their own tone and pitch of voice, their own accents and dialects, their own slang and stylisations. Their voices and expressions have been used and inserted in places they do not have access to many times through people acting as their mouthpiece. For instance, Wizkid, Burna Boy, and some other Nigerian musicians are played on the radio in Europe, and some slangs and expressions in their music belong to “area boys”, belong to the street.

Considering that men on the streets like to portray themselves as strong and powerful, how did they feel about being photographed in their private spaces and showing their more intimate side?

I would say the access I got into their lives wasn’t necessarily because I am an artist or photographer. Opening myself up to them in a way that left me vulnerable was a gesture of trust, which I noticed wasn’t generally accorded to them. I sat under the bridge with them from morning till night, day after day, during which time I was not actively photographing but just being present with them. There was no pressure to take anything from them or ask them to do anything for me. Over time, I realised they got comfortable enough to invite me into their homes, enough to stop apologising for how less than “ideal” the pákó houses were. I witnessed their vulnerability and sensitivities, and they witnessed mine when we all get irritable. There was no way I could do my work behind a wall. I had to let myself be seen so I can see them for who they are without the façade of toughness and the face they present to the world while they try to survive on the street. It wasn’t pleasant all the time. The “I run this place, I am strong and powerful” thing was a continuous dance that sometimes got overwhelming.

Do you think these kinds of projects can start conversations about Nigeria’s reality of economic hardship, corruption, and governmental negligence? Is it all political for you?

The truth is, for this project, I wasn’t concerned with the local politics in Nigeria. Although, by its very nature, the project does seem political, my interest was less in the local politics and more in what I would call personal politics. There’s so much to the lives of the people we seem to know only superficially. If you live in Lagos, you know there are area boys, but do you really know them? I also wanted to show the sense of community between them and show that irrespective of the social strata—whether you live on the island or the mainland—we are not so different. To show that we are all just human after all.

More so, I don’t see them as “area boys”, though this is what we all call them. If you ask them, as I have done many times, they would tell you they are not area boys. I like to see people as they see themselves. And so, I like to see them as people who are in the city of Lagos hustling to make a living just like everybody else.

I think all my works connect in some way to each other. They exist in a kind of continuum and are all linked.

Should area boys be taken off the streets and re-educated? Do you think the government needs to rehabilitate them?

Why do they need to be rehabilitated? If they need rehabilitation, then every Nigerian needs rehabilitation. The truth of the situation is we are, in one way or another, victims of a flawed system, a non-functioning society. The fact that you can afford your one room or the basic decencies of life doesn’t mean you are shielded from the problems that plague Nigeria. I don’t have electricity. They don’t have electricity. I don’t have water. They don’t have water. The fact that you or I may seem a little better off doesn’t mean we can compartmentalise another and assign these people a different place from ours. If the political and economic situation of Nigeria were to improve, their lives would also improve. There would be job opportunities and better prospects, and no one would need to “play saviour” to anyone.

In an interview with Wana Udobang on Culture Diaries, you talked about what it is like living and working in Germany. You described it as a place where you can find your stillness. I find that interesting. Can you talk more about this “stillness” and if it is possible to achieve this in Lagos?

I don’t know. I think yes and no. I mean, finding stillness involves a lot of things. In a place like Germany, unlike in Lagos, I don’t have to worry about my phone, my computer, internet, water or other such basic things, which would drive one mad in a place like Lagos. I do not have to think of leaving my home four hours before an appointment. So, if you have to deal with all these things—which we have to deal with as Lagosians—you get off balance. It has a way of messing with your head. Still, there are people in Lagos who don’t have to deal with these things. They are shielded. When people talk about being held up in traffic, for example, they look at you because they don’t sit in traffic or go through what you go through. Although they live in the same city, these people have structures that protect them from the reality of an average Lagosian. For such people, who do not have to worry about water or electricity or the internet, maybe they can find their stillness.

In a system that doesn’t necessarily support art, in a system where there are no structures to encourage creativity, people have to find a way to make their own space to create. Now I know, of course, that things are going on. Galleries are opening for artists to sell their works and all. But these are spaces that cater to business. While these are important, we also need more spaces to cater to the creative process itself, spaces that allow artists to experiment and do the work they want to do, and outside of the city’s stress.

How is Born Throw Way! connected with Pilgrimage, the work you presented at the 12th Bamako Encounters in Mali? Or more broadly, is there a particular thread that connects all your work?

I think all my works connect in some way to each other. They exist in a kind of continuum and are all linked. Across my works, an element of the self is very present. In Born Throw Way! this is quite evident. Also, there are the strong themes of belonging and non-belonging, of who gets discarded. In a project like Beautiful Decay, I look at waste; in Born Throw Way! I make a somewhat similar examination, inquiring into how society looks at certain people as waste, as something to be discarded. So there’s a connection that runs through all my works.

___

Adéọla Ọlágúnjú is a photographer and visual artist working across different media. Through conceptual and deeply psychological works, she explores identity, banality, human agency, and environment. She has had residencies and fellowships around the world. In 2019, she won the Grand Prix Seidou Keita Award at the 12th Bamako Encounters, the African Biennale of Photography.

Joseph Omoh Ndukwu is a Nigerian writer and editor. His work has been published in the Prairie Schooner, Guernica, Saraba, Brittle Paper, and elsewhere. He lives in Lagos, Nigeria.