When Antonin Artaud published The Theatre and Its Double in 1938, it was with the intent to charge and change the perception of theatre and its possibilities. In his manifesto on The Theatre and Cruelty, he writes, “The theater must give us everything that is in crime, love, war, or madness, if it wants to recover its necessity.” Artaud rejected the supremacy of language in theatre and believed in its physicality, a “revolving spectacle” that can “attack the spectator’s sensibility on all sides.” There’s something akin to that Artaudian sense of theatre in Syowia Kyambi’s Double Consciousness, which was performed on 10 December 2018 at the Alliance Francaise, Nairobi, as part of celebrations marking the 70th Anniversary of the universal declaration of human rights.

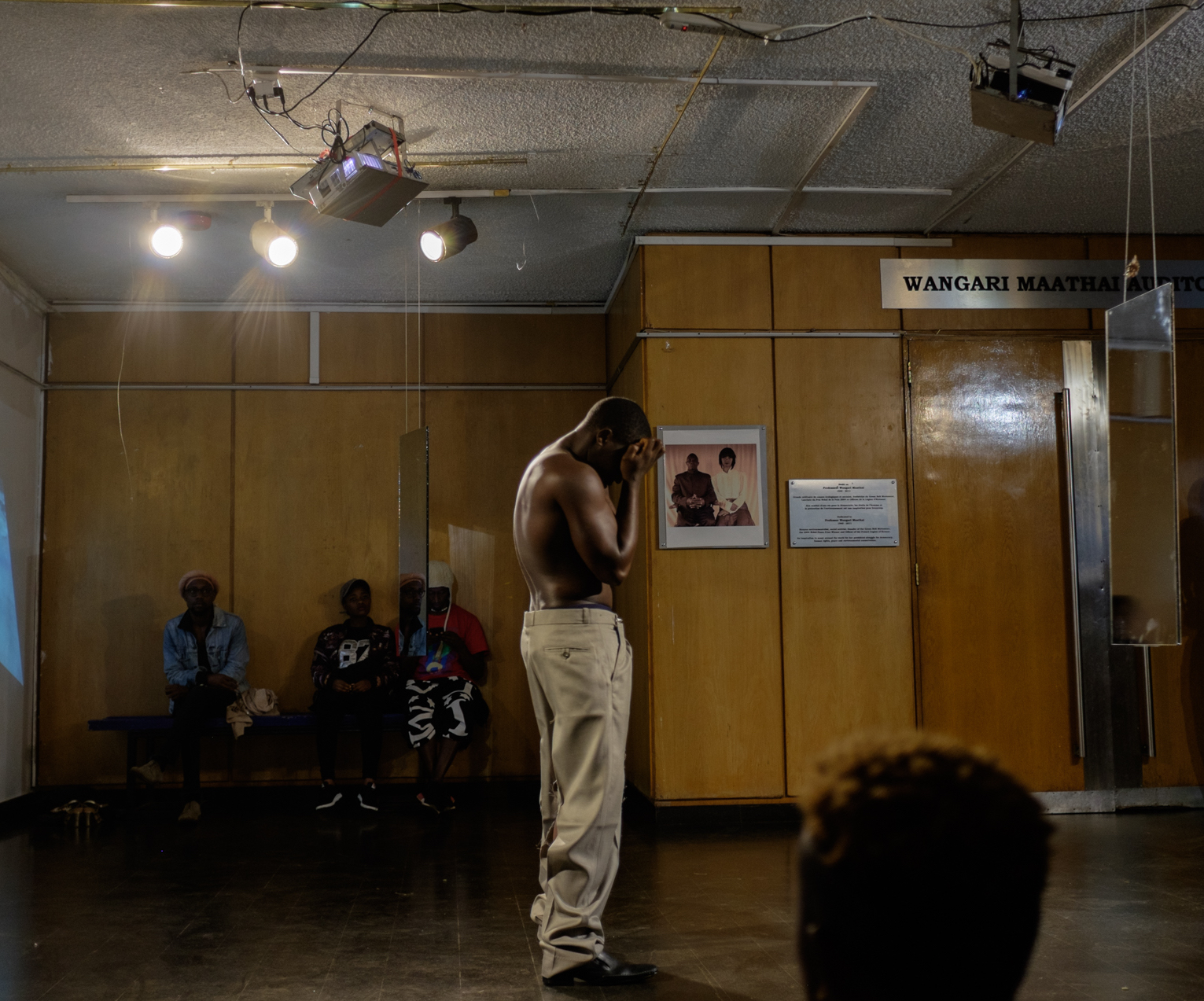

Double Consciousness is a combination of installation and performance. The installation staged in front of the Wangari Maathai hall at the Alliance Francaise, just by the steps, comprised of double-sided mirrors hanging from the roof, ropes bearing combs and suits, a background of projected sky, and a lone high chair. These were all part of the mise en scène for the performance that would later begin when Kyambi, a lone figure bent among the audience, started to shed her street clothes. Stripped to her underwear, she approached the stage, which at the time was filled with members of the audience trying to find a perch from which to witness the performance. This, too, recalls Artaud, who wrote, “we abolish the stage and the auditorium and replace them by a single site, without partition or barrier of any kind, which will become the theatre of action.”

As Kyambi climbed the ‘stage’, she moved past a man (Samuel Mutie) dressed in a Kaunda suit and seated on the high chair. She approached a shiny cheap-looking suit hanging to the side of the stage, and with the help of the audience wore the suit, put on stockings, shoes, and styled her hair from flourishing afro to a tamed braid covered with a wig. As she did this, the man came down from his high chair and stood menacingly around her, shadowing her movement from one hanging mirror to another, leading to a violent scuffle. The fight ended with the man’s suit torn and the woman dragged off the stage, into a heap at the feet of the audience.

Following this act, another woman (Waigwe Mwangi) came into view as she changed into the red and white uniform of a housekeeper, complete with an apron. She cleaned the mess left by the warring couple, sewed the man’s torn suit, and brought the man and woman back to the centre, one after the other, to care for them.

The scene of the performance was domestic and the roles played by the characters were easily identifiable. That the characters changed into their roles right in front of the audience emphasises that the domestic setting is a kind of theatre too, one where power is played out in ways that reflect dynamics of the broader world. A woman tames her wild parts to fit an image in the home. Her man monitors this change, and their interaction leaves a mess for other people to clean up, some who have to suspend their own lives to cater for another. Identity, gender, and class all play out in the tight intimacy of the stage with people crouched around it, which is made expansive by the presence of double-sided mirrors and the projected sky.

The choice of Double Consciousness as title of the performance moves its political underpinnings beyond a mere hunch. In the first chapter of his book The Souls of Black Folk, titled ‘Of Our Spiritual Strivings’, W.E.B. Du Bois established the term “double consciousness” when he wrote, “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

We are narcissistic people who cannot escape our own images, but also voyeurs who participate in this prison experiment we call reality…

That sense of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” is present in Kyambi’s performance—the woman character who puts on a costume for her role is being watched by the audience, and even much closely by the man who stands in front of her. By fitting into the suit from her street clothes, and putting her body in tights and wigs and other things that keep her body in check, she’s tacitly making herself fit for the gaze of her spectators. She’s not just looking in the mirror to examine her true self, but to be sure she can see what those who are watching her need to see.

The ensuing fight of the couple makes it clear that metering appearance to fit an oppressor’s gaze is not a guarantee of anything. Even when oppressed people make themselves less of a threat in the Du Boisian sense, it does not result in an assurance that they won’t be treated with contempt. The mess created by the couple is left for another to take care of. The housekeeper is, therefore, defined by her usefulness to the couple, even when it is apparent that she enters the stage from a world where she’s no different than the woman and the man, at least in body. Here, before the watching eyes, her role is to cater to the needs of others.

In spite of the fact that all the characters do not speak, the silence of the two women is amplified because they are reacting to realities foisted on them. The need to conform to a specific image, and resistance to the violence of the man for one, and the state of the mess created for her to clean up, for the other. But whereas one woman is able to react to the violence of her man in her actions, the other reacts to an obligation to care and performs her duties with a stoic face. The involvement of these women extends the performance beyond the concept of double consciousness as defined by Du Bois into “triple consciousness” as defined by scholars who came after him. Kyambi’s identity as an Afro-German also creates an adjacent way to consider this consciousness, one that intersects race with gender and class.

“Mirrors and poetry, as well as myth and fairytales, refract reality in unexpected ways,” writes Joan Jonas, known for her pioneering 1969 performance Mirror Piece I. “Mirrors can collapse or confuse the distance between performer and audience and disrupt visual frameworks.”

The presence of mirrors in Kyambi’s Double Consciousness, as it was in Jonas’s Mirror Pieces, emphasise the importance of the presence of an audience in the performance and installation. This examination of selfhood and fragmented states of being isn’t satisfied with being a mere spectacle for the audience to behold. We see ourselves, not just metaphorically in the characters that play out on the stage, but also physically in the mirrors that return our images and place them side by side, first with the actors, and afterwards with the pieces of the installation: a torn Kaunda suit, a woman’s wig, a housekeeper’s uniform, and stockings. We are narcissistic people who cannot escape our own images, but also voyeurs who participate in this prison experiment we call reality, where we cast oppressive gazes on others, even as we attempt to mould ourselves into beings that can survive the mess we have made of the world we live in.