On the three separate occasions that I have visited Nairobi, someone has told me how every Nigerian story includes the harmattan. It’s a joke that I think hits home but has worn out its welcome. Nairobi, this December, however, is very much like harmattan-dusted Nigeria, especially with the temperamental weather. There is rain in the morning, heat in the afternoon, and cold at night. Nairobi is also like Lagos in so many ways that I often say “Africa is a country” ironically whenever something happens that recalls home. The arts in Nairobi is one of those things that reminded me of Nigeria, at least at some of the galleries I visited.

For art to travel wide, it is often assumed it has to lose any idiosyncratic identity, particularly in its presentation. So, a gallery in Lagos is supposed to look like one in Nairobi and they should both look like another in New York. Spaces like Massai Mbilli Artists collective, located in Kibera, which serve as a haven for artists who want their individuality to find a home, do not bear this bland sameness. But three of the other spaces I visited, their walls and presentations were very unoriginal, and in this way meet what we often refer to as international standards. Yet, in this apparent uniformity, the three galleries couldn’t be more different once you get over the familiar – both in the arts displayed and in their perceived goals.

Circle Art Agency, located on James Gichuru Road, was the first of these three galleries. At the time of my visit in mid-December, the gallery was showing an exhibition of works by young artists from Zimbabwe called Harare Contemporary curated by Valerie Kabov. As a glimpse into contemporary arts in Zimbabwe, this exhibition is varied in the forms presented. It is a buffet with something for everyone. I was drawn in particular to the three-dimensional works in the exhibition by Takunda Regis Billiat, Julio Rhizi and Wycliffe Mundopa. They were well crafted, colourful and different enough to be curious about the process of their making. The combination of paintings, installations, sculpture and recorded performance by the young artists offer a window to the vitality of contemporary art in Zimbabwe, which should be enough for anyone interested in art from the country to explore even more.

In this way, Circle Art Agency seems to position itself, not just as a space in Nairobi that caters to the arts in Kenya, but also as a window for Kenyans to explore art from other countries in and outside East Africa. It seems this is the mission that drives the agency and behind the variety of works featured in their annual Arts Auction East Africa, which has featured art from all over the continent since 2013 and has become the region’s premier art auction. And perhaps the reason Circle Arts Agency was present at the 2018 Art X Lagos, in the company of two other galleries from East Africa. It’s important that Africans are able to see and buy arts from different parts of the continent, and Circle Art Agency continues to make this happen through its gallery and auction.

One Off Contemporary Art Gallery, located off Limuru road, about 13 kilometres to the North of James Gichuru Road near the end of Nairobi County, was next. Now, you will need to ignore what I stated earlier about the sameness of the gallery spaces so I can convince you that this space is very different from the Circle Art Agency. Where James Gichuru is close to the heart of Nairobi City, and the casual visitor can just drop in to take a look at the art in the white cube space and sneak back into the city, going to One Off requires some commitment. The Gallery is well off the beaten path and tucks snugly into the woods in Rosslyn so much that if you pay attention you’ll hear a stream swish by.

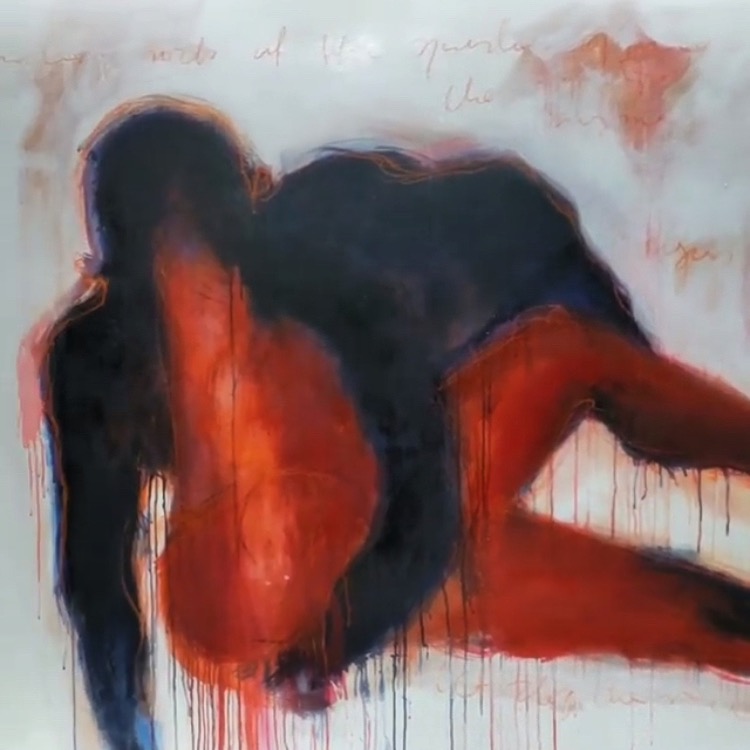

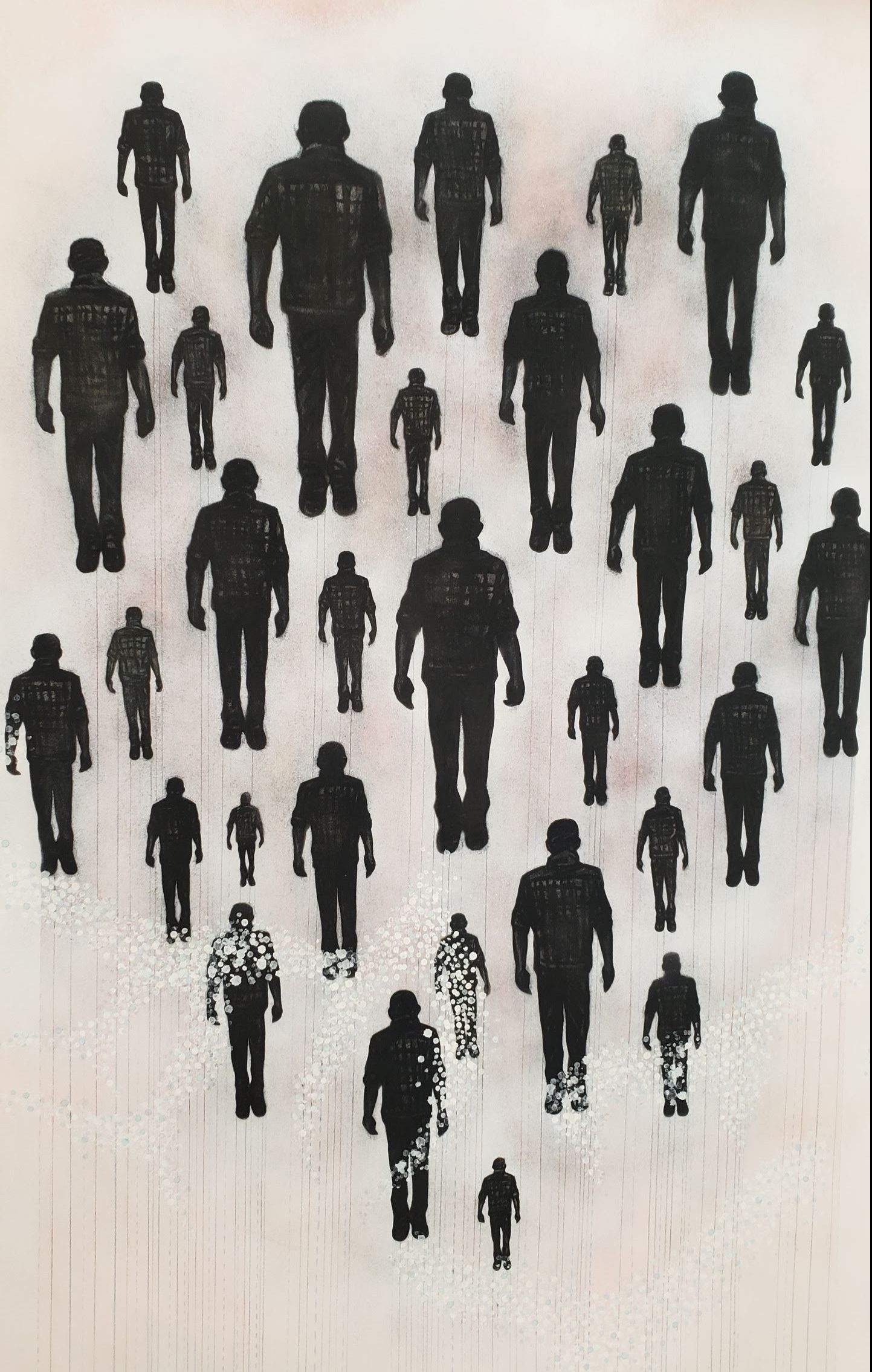

At the time of my visit, there was an ongoing exhibition by Peterson Kamwathi at the main exhibition space, with glass sculptures by Naomi Van Rampleberg also on display. Kamwathi’s exhibition titled Ebb and Flow represented the best of the artist’s three-year fascination with migration. It included drawings of different sizes in small frames to large size triptychs, all done with his characteristic meticulousness. In the Gallery’s second space were paintings by Beatrice Wanjiku. There were also works by young artists fresh from art schools who exhibit in the space too. One Off represents some of Kenya’s most well-known contemporary artists and after a walk through the gallery space, if my one-day experience is indicative of its competence, these artists are in good hands.

My final stop exploring Nairobi galleries was at Red Hill Art Gallery of Contemporary African Art, located about 13 kilometers north of One Off gallery, in Kambu County, just outside of Nairobi county. If going to One Off requires commitment, a jaunt to Red Hill demands proper planning, which should include transportation for a round trip. Hellmuth Rossler and Erica Musch-Rossler built Red Hill in Kenya when they retired from working in different countries on the continent. This was both a way to keep their vast and impressive art collection, and also provide space for Kenyan artists to show their works. Joseph Cartoon was exhibiting at the time I visited, and Hellmuth took his time to talk about Cartoon’s work and the progression visible in his paintings. Red Hill Gallery runs as a non-commercial space and holds exhibitions for longer periods than One Off Contemporary Art Gallery and Circle Art Agency.

This long period of exhibitions is, actually, a feature of the three galleries, and what makes them different from their Nigerian counterparts. While there are gallery spaces that hold exhibitions for extremely short periods of time similar to the practice in Nigeria, like the Kobo Trust, which offers its space for artists to display their works, there’s a sense that the galleries here are invested in offering an opportunity for many people to see the exhibited art.

Hellmuth and Erica also invited me to their living space to experience a part of their incredible collection; a generosity and openness I presume must be heartwarming to the artists whose work they collect. The collector base in Kenya is still very white—another difference from the Nigeria art scene — but art managers like Don Handa and Kui Wachira talk about the growing numbers of Kenyan collectors with hope in their eyes. And even though my cynicism about the inner workings of the art world means I see the Rosslers as an exception — foreign collectors who are not just hawks sweeping to grab the best work and make them vanish into private spaces, never to be seen again—the enthusiasm of the Kenyans working in the spaces themselves make me pocket my skeptical thoughts and enjoy an art scene that is confident in its own development and growth.

Visiting three galleries isn’t enough to get a sense of the entire history of contemporary art by artists, curators, and art managers in Kenya but there’s comfort in the knowledge that, even without reading up on lists such as the one provided by Seribiri Moses in the publication Africa is a Country, a mere ride through galleries in Nairobi is able to leave anyone with humility to acknowledge the fantastic work that is being done.

You have lots to catch up on on bro.