Farah Khelil proposes ecology and archive digging as possible means of decolonization in her practice that integrates nature, images, sound and text.

Tunisian artist Farah Khelil (1980) works and lives in France.

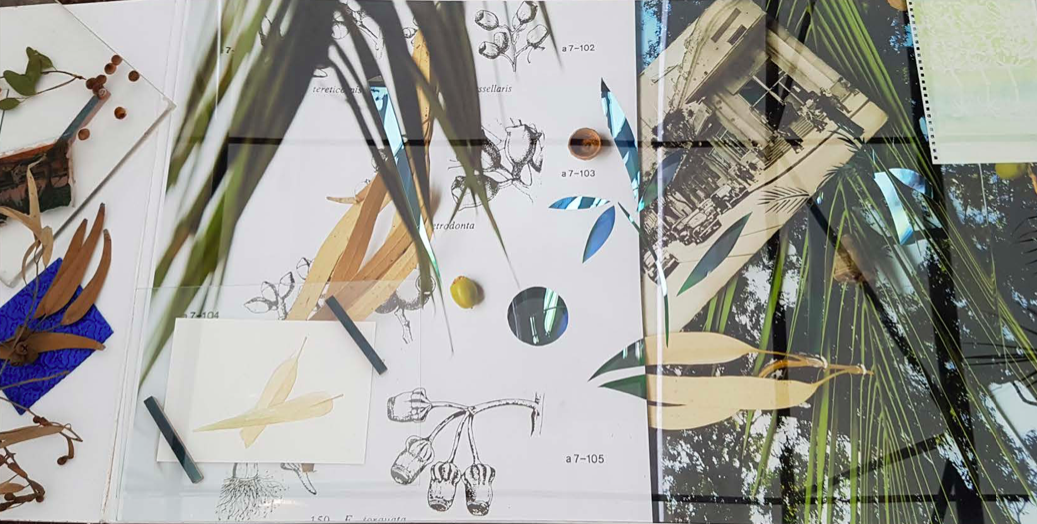

Khelil’s multifaceted works are arrangements of images, objects or texts that she transforms into physical or sound installations, reconfiguring their meaning. She uses protocols of translation, coding distancing and blindness, employing games of composition and analogies of meaning. Drawing on a variety of techniques and materials, these works shape a reflection on the relationship of art to writing, language and information.

To me, Khelil is the most subtle anarchist I know; true to herself, her artistic freedom of speech and her freedom of topic choice. Through her carefully designed exhibitions, she uncovers the weakness and hopelessness of old approaches: institutional, artistic, political. Through extreme elegant and complex gestures, she shows where the colonial perspective has led us and how much she dislikes it. Through her artworks, she constantly reinforces the non-commercial and non-institutional objectives of art.

To me, Khelil is the most subtle anarchist I know; true to herself, her artistic freedom of speech and her freedom of topic choice. Through her carefully designed exhibitions, she uncovers the weakness and hopelessness of old approaches: institutional, artistic, political. Through extreme elegant and complex gestures, she shows where the colonial perspective has led us and how much she dislikes it. Through her artworks, she constantly reinforces the non-commercial and non-institutional objectives of art.

Having said that, I have some questions and notes for the reader: how do you meditate on images? Have you ever wondered how far into an artwork you can or want to look? Or rather, how close the artist will let you look?

– – –

Effet de Serre (eng. Greenhouse Effect) was an exhibition organized in a recreated greenhouse in the old Belvedere Parc in Tunis, Tunisia. A very special place because from the beginning it was meant to dazzle with its aesthetic construction and show plants as inanimate objects ready to be admired by the viewers. You can read more about the exhibition itself and the project here: curatorial text by Clelia Coussonnet along with a visual portfolio.

I spoke to Khelil twice, first in the middle of the first pandemic year 2020 and then in early 2022 (still) during the pandemic, the refugee crisis on Polish territory and on the verge of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Imagine that you are an artist who looks after her project how a computer scientist looks after his software code. She makes plans, deals with logistics, researches objects’ history and their emotional charge long before she puts them in the public eye. Or, long before she decides not to show it to you, as to whistle about it.

You may begin to wonder how it happened that the artist collaborated closely with the municipal authorities. Here, please, consider your thoughts and experiences with any municipal institution you have ever had to work with. Was it good cooperation? Did they listen? How freely were you able to express your personal views to the official?

Bearing this in mind – given that Effet de Serre was a process scheduled to be implemented during 2019 and 2020 – are you able to feel the pain of being involved in artistic creation while at the same time being involved with endlessly ping-ponging with the municipal office?

Such questions help me to explore the relationship between living stories and seemingly dead artefacts.

How would your body and your decisions about moving in this isolated microcosm interfere with its objects, ideas and memories behind them? Would you be the one to discover these “secrets”? Or would Effet de Serre treat you, your presence in the world, and your cultural and racial background as a rare export commodity that needs to be seen, and then archived?

By the way, how aware are you of your senses? Can you touch something? Think about it because the idea of a perfect exhibition in a white box is beginning to be slightly distorted here.

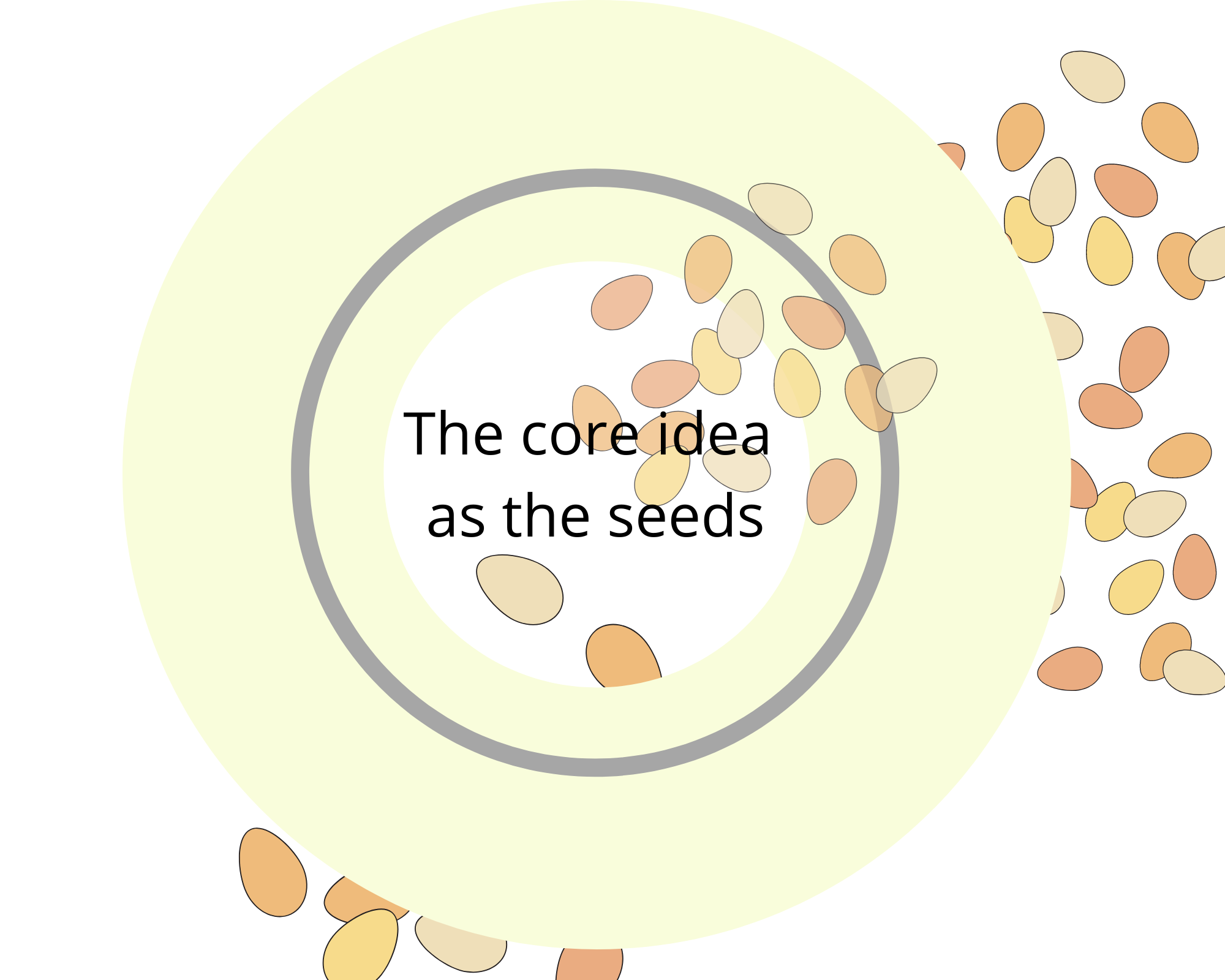

The story of two plants – and their seeds – is representing not only the objects of archival interest and the objects that would be perfect for exhibition in a greenhouse built on Tunisian soil. A palm tree – native to the territory – and an alien that just grows here, the eucalyptus are also a representation of the complex history of this land, and of colonizing acts in general. A double identity, observed in warm and isolated infrastructures (of a greenhouse, of Khelil’s exhibition, of visitors’ memories). What does this exploration mean to you: do you notice an already colonized landscape full of eucalyptus trees? Would you fight with traditionalists to ensure that the environment consists only of “palm trees”?

The more you think about it, the better. How much of this observed and obvious division of the world (whether it is your childhood playground, the art world or the cultural idea we are talking about) is just capitalist market rules imposed on every piece of information, culture and artwork? How much is cataloguing and dividing into clear sections worth to you? At this point, I want to stop you. The most important and necessary change in the (art)world is to break the colonial approach. However, this process cannot be limited to certain objects and cannot be carried out by those who invented it.

As Ariella Azoulay states: “It is not possible to decolonize […] without decolonizing the world. It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t engage with this important work, but we have to do so with the full awareness that decolonization cannot be limited to discrete objects, museums, or archives, and cannot be substantial as long as the people from whom all this wealth was expropriated are not allowed to lead the process.”1 To break every “universal” standard and every scope, go back to the seeds and plant them as decolonized ideas; this is where the new (art)world will begin.

– – –

In these times, torn by wars and plagues, let us hope that artists will be saved. Maybe one day, another Khelil will consider our stories fertile soil for a tender tale, a wise observation on the nature of humans and non-humans. A powerful insight.

Because, I believe, power circulates in networks. Not just social ones, but also networks of meanings, clusters of personal and collective beliefs or memories, in landscapes filled with plants and timescapes filled with events.

Hopefully, through projects like Effet de Serre, art museums will become true witnesses to our stories: alive and responsive, like the gardens that will grow upon us.

Images 1/5/7/8: Installation view of ‘Effet de Serre’ (2021) by Farah Khelil. Courtesy of the artist

Featured illustrations by Weronika Morawiec

–

Weronika Morawiec is a writer and curator from Poland. In 2019 she participated in the Curatorial Intensive program of the Lagos Biennial. She cooperates with: Goyki3 Art Inkubator, Tunis Central art association and Selma Feriani Gallery.

1 Quote from a brilliant talk between Ariella Aïsha Azoulay and Sabrina Alli https://www.guernicamag.com/miscellaneous-files-ariella-aisha-azoulay/ [online access: 10.02.2022]