The Museum of Black Civilizations opened its door to the public in a grandiose yet solemn fashion in December 2018. Heads of states and important guests from the continent and its diaspora attended the opening ceremony. Official speeches were followed by a series of performances from the likes of choreographer Germaine Acogny and the musician Baaba Maal. The museum, for decades a negritude dream, now an architecture, a temporary exhibition and an institution, is grappling with the ambitious, challenging and perplexing mission it has been endowed with.

Those entering downtown Dakar have long been accustomed to the monumental spheric shape sitting in between the Grand Théâtre Nationale and the belle époque train station. It covers 15,000 square meters, cost almost 35 million dollars and was funded by Chinese aid. The ochre building’s structure is a homage to southern Senegal’s vernacular architecture with its impluvium design. Where the impluvium’s central area is open to rainfall, the museum, with both its central glass roof and wide windows, allows for the ubiquity of natural light within its walls.

Although the idea of an institution that would illustrate the continent’s contributions to world heritage can be traced back to the 1959 congress of black writers held in Rome, it was in Dakar, during the 1966 World Black Festival, that it crystallised into a state-sponsored project. During the now iconic festival’s seminar, titled Function and significance of black art in the people’s lives and for the people, a series of contributions drew attention to, and lamented, the displacement and erasure of objects that bear witness to Africa’s civilisation before western colonisation. Anxious to claim that black Africans too had a civilisation, that generation of intellectuals felt an urgency and expressed an outcry in the face of massive smuggling of artefacts out of the continent and the estrangement of the new generations of christian, muslim and or secular-minded Africans towards those objects that belonged to fading social structures and episteme. The late Professor Ekpo Eyo, whom with Wole Soyinka was one of the Nigerian intellectuals to speak at that gathering, pointed in his paper to the necessity of museums that would allow for both the safekeeping and studying of those artefacts. The seminar, among a series of recommendations to African heads of states, some of which had supported the event, listed the necessity to build national and regional museums. Léopold Sédar Senghor, during the event, announced the creation of the Musée des Civilisations Noires and entrusted the project architecture to the Mexican architect Pedro Ramirez Vasquez, who designed the National Anthropology Museum of Mexico and to the Swiss writer and ethnologist Jean Gabus. The latter, curator of the Neuchatel ethnographical museum, thought extensively about reimagining the museum as a space and an institution and came to be, over the years, an important asset for Léopold Sédar Senghor’s cultural policy. Decades would pass though, before the first brick of the Musée des Civilisations Noire would be laid, in 2003, during Abdoulaye Wade’s presidency.

The Museum of Black Civilisations poses a series of questions. Black civilisations, as it is recognised by the museum’s direction, is a problematic syntagma. The idea of civilisation, which we know colonialism justified itself with, should be unpacked and deconstructed.

Facing the visitor entering the hall, at the centre of the atrium, rise a towering metallic sculpture, The Saga of the Baobab, by Miami-based Haitian artist Edouard Duval-Carrie. The piece, grounded at the very heart of the edifice, communicates ideas of rootedness, strength and flourishing. Duval-Carrie, contacted by the museum to work on an original piece, thought of both the Baobab tree and its Caribbean sacred tree counterpart, the Mapou. He had the piece built on his native island using local crafts and materials, as if to transport, with the piece, the soul of Haiti into Dakar. The central location of his work emulates the potomitan, the central post in a voodoo temple. The Saga of the Baobab ascends all the way to the top of the structure and can be seen from all the internal gangways. The main floor of the exhibition space is structured in two rooms and two central concentric circles that welcomes the exhibition titled African Civilisations: Continuous Creation of Humanity. Directly surrounding Duval-Carrie’s work is a series of millennia old objects that bears witness to the continent as the cradle of humankind and technological conquests. Remnants of primitive hominids, of arrows, of cut stones and fishhooks; screens with three-dimensional representations of early human species, photographs of pre-historic drawings and carvings cover the curved walls. Enclosing that room, through a series of panels, is a depiction of the classical scientific and technological discoveries of the continent as observed on written sources, objects and architectural remains.

Interestingly and considering the project’s origins in the negritude era, one can see, in the inaugural exhibitions, the influences of not just Léopold Sédar Senghor but also of his intellectual nemesis, the late Senegalese polymath, Cheikh Anta Diop. The influence of the museum’s director, Pr. Hamady Bocoum, an archaeologist known for his work on metallurgy, is also visible in the exhibition’s emphasis on the iron age and its reliance on the discipline of archaeology. The objects and texts gathered tell stories of an ancient past, of times blackness didn’t signify what it does in our postmodern times and yet, a bridge is created within the space, between the age of those artefacts, stones, metals and bones and with that of the Black Atlantic which Duval-Carrie’s piece summons. The space, the scenography and the curation composing the overarching theme African Civilisations: A Continuous Creation of Humanity suggests such many juxtapositions of temporalities.

Still on the first floor, the ethnological exhibition African Civilisations is a collection of textiles, musical instruments, sculptures and masks from different regions of the continent, most spanning from the modern era and some from ancient Egypt and Nok. Pieces from the area that is now Nigeria and the zone that was once covered by the Mali empire dominate the exhibition, although sculptures and masks from southern Côte d’Ivoire, Dahomey, Cameroon, the latter being stylistically quite remote from the west African pieces, are also present. Many of the pieces on display are familiar, such as the Nok anthropomorphic terracotta statues, the Benin bronzes and the highly stylised Bamana zoomorphic wooden statues. Although the statement of intent at the entrance of the room puts the emphasis more on the ethnological values of the objects, the cosmogonic thinking that they materialise and the social structures they stem from, than on their aesthetic, the information provided on each piece is quite minimal. In their report on restitution, Felwine Sarr and Benedict Savoy use the concept of resocialisation, as a way through which objects that were taken in African societies and making sense within those particular societies can be reinvested by meaning in new, contemporary sociologies and imaginaries. Thinking along those lines, the exhibition African Civilisations can be thought of as a site of resocialising African classical art.

Beyond that room and along the wall that leads to the first floor, we are presented a mosaic of familiar faces, photographic portraits of male historical black figures. The dreamy look of young Thomas Sankara counterposing the stern expression of Frederick Douglas. A second mosaic, on the first floor, is devoted to female figures such as Angela Davis, Mariama Ba, Harriet Tubman, Winnie Mandela, the Nardal sisters, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and Wangarĩ Maathai among others. Running along that same gangway are a series of textiles from West Africa and an exploration of the mask as a universal form with examples from the Americas, Asia and Oceania.

Two contemporary art exhibitions are located on that same first floor, Africa Now and The Caravan and Caravel. Africa Now, a kind of the best of the Dakar Biennale, is mostly a collection of works from artists that have, over the past years, won the first prize of the Biennale of Dakar. It opens with the latest winner, an eerie photographic series, Malaîka Dotou Sankofa, by Laeila Adjovi and Loïc Hoquet. The usage of textiles in the photographs introduces that material which is omnipresent in the exhibition. A monumental piece of Yinka Shonibare, made of brightly woven coloured fabrics, Odile & Odette, occupies as unrolled on the floor central place in the scenography. Next to it, a gang of anthropomorphic and willowy sculptures by Ndary Lo raises their hand to the sky. Climbing the opposite wall is Olarenwaju Tejuoso’s Oldies and Goodies, composed with scraps of consumer goods packages. An installation by Mansour Ciss Kanakassy, the Deberlinisation Lab, shows huge lighting matches planted on sand, some burned some still intact, and alludes to the decolonial process, pointing to achievements and remnants. Olu Amoda’s Sunflower, another laureate of the Biennale of Dakar, contrasts the frailty of its subject, a flower, with the roughness of its materials, metal scraps and cutlery. Two pieces by Abdoulaye Konaté appears in the exhibition, both use textiles and alludes to Mali, Dogon Couple and the fierce Tribute to the hunters of Mali which mixes a myriad of talismans on an ochre piece of Bogolan fabric.

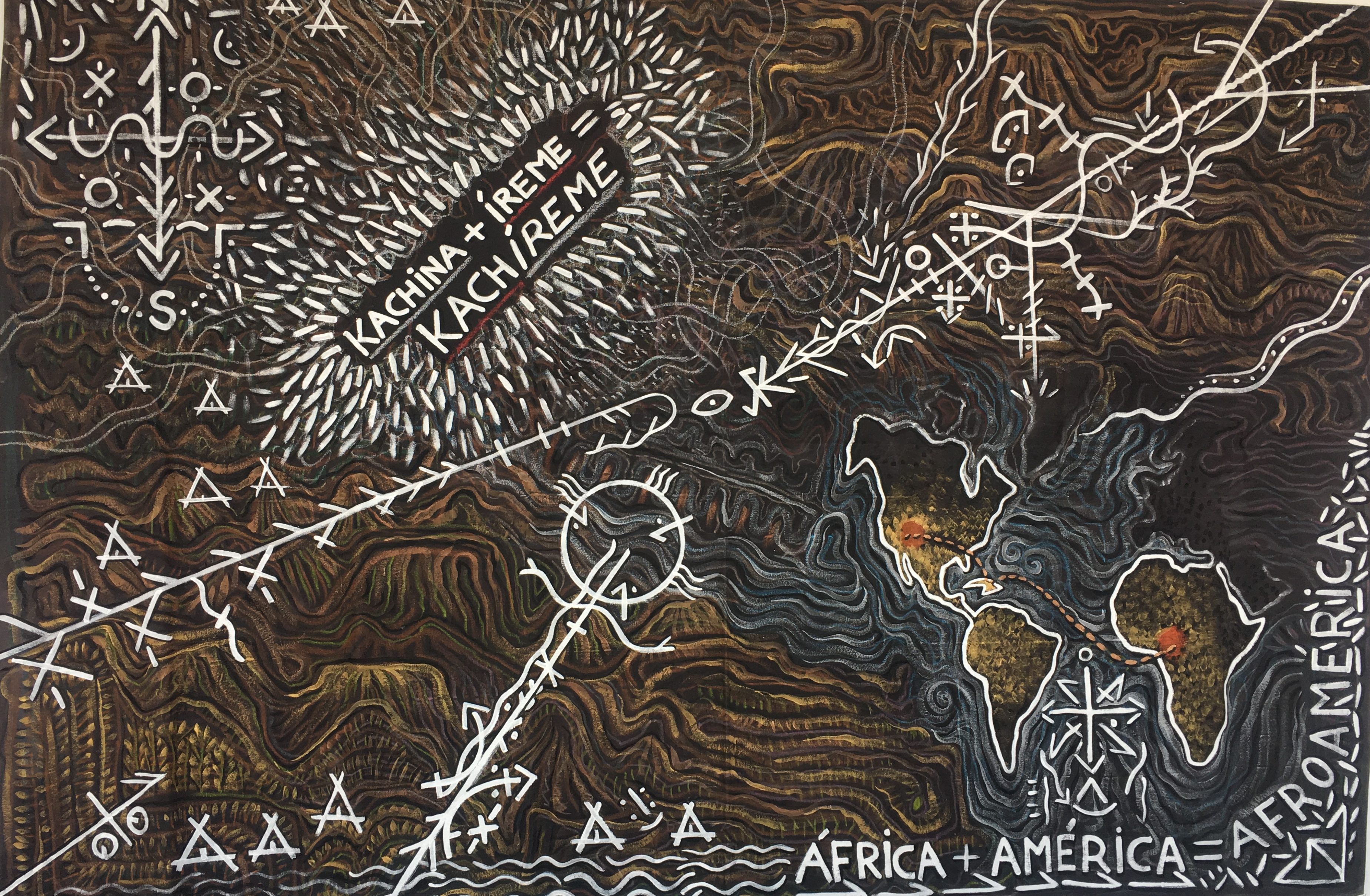

The other contemporary art exhibition, The Caravan and Caravel, brings together works of Afro-Latin-American artists, with Cuba being the most represented nation. It is arranged along a passageway and in a vast white room. The small size flat bronze sculptures of Alberto Lescay Merencio, silhouettes of different beings coming together in a single form, sits along the bay window, appears in the backdrop of Dakar’s cityscape. The sight of those alone would justify the visit. Some of the other works on display are mixed-media paintings from Leandro Soto’s series Kachireme that blends African and Mesoamerica mythological narratives, Philippe Dodard’s black and white paintings that draws inspiration from both African and Amerindian iconography and Douglas Pérez’s tryptic Romance de la Garde Noire. A powerful installation by José Angel Toirac, made of a disposition of camouflage apparels, canteens overlooked by portraits, titled Meira Marrer Octavia Marin, stands as a homage to the 2077 Cuban internationalist who fought and died in liberation struggles in Algeria, the Congo and Angola.

Although it harbours precious artefacts of the past and powerful works of art, the Museum of Black Civilisations poses a series of questions. Its very denomination first. Black civilisations, as it is recognised by the museum’s direction, is a problematic syntagma. The idea of civilisation, which we know colonialism justified itself with, should be unpacked and deconstructed. That the independence era generation would have clung to it and thought that their duty was to demonstrate that they had any made sense; not anymore. A project that takes blackness as its object and the whole history of humankind as its scope, from the advent of homo-sapiens-sapiens to our days, is doomed to an anachronism. Yet, judging such an institution in its early days and on its first exhibitions doesn’t make much sense. The Museum is still, hopefully, inventing itself. Besides, conceptual uncertainty is a fertile ground for asking questions rather than giving answers, and hopefully, the Museum of Black Civilisations can embrace that rather than institutional and intellectual rigidity.

_

Mamadou Diallo is a journalist and writer from Dakar. He was an editor at the publishing house Vives-Voix and wrote extensively on the local art scene specializing in young and emerging creatives. A graduate of history and fellow of the Raw Academy in Dakar, he won the Ake Arts and Book Festival Prize for prose in Nigeria in 2015. He is a contributing editor at Chimurenga, where he recently published the captivating long essay The Black Bomb.