How do we process images rooted simultaneously in the fantastical and the mundane?

A scene in a painting opens up before us. A boy is fitted for new clothes in a tailor’s shop, attended to by two seamstresses. One kneels by him, taking measurements, while the other sits behind a sewing machine, watching. The boy’s head is turned slightly to the right towards the seated seamstress, an excited look on his face. The scene is familiar and intimate, evoking nostalgic feelings of visits to the tailor and the anticipation of new clothes for special occasions. However, the familiarity we feel with this scene is offset by golden wings sprouting from the backs of the seamstresses. For a moment, the fantastical and the mundane exist as one.

New Raiment (2014), the painting described above, is part of a series of paintings and installations shown in the solo exhibition of contemporary Nigerian artist Demola Ogunajo. Organised and presented by kó Gallery, Lagos, the exhibition titled Area Art brings together intricately detailed and multilayered works made over the course of several years from the last decade. Building on his project Animystic City which explores the connection between spirituality and the urban space, the works in Area Art employ symbolic imagery from mythology, religion, pop culture and street slogans to create hybrid worlds of astronauts, mythical creatures, household items, directional signs and futuristic landscapes. With this exhibition, Ogunajo makes visceral the intimate textures of modern life and street culture. In its exploration of the philosophical complexities of modern life, the exhibition considers the formation of meaning and aesthetic ideologies through a close reading of populist culture and archetypal imagery.

The presentation, curated by Joseph Gergel and Medina Dugger, stretches across two rooms, essentially dividing the exhibition into two parts. The first room primarily features paintings of densely and elaborately arranged images, text and intricately detailed landscapes, while the paintings in the second room feature portraits of animals and characters from old animated children television series and loosely constructed compositions. Ogunajo’s stylistic approach is graphical and illustrative, drawing on his extensive work as a graphic designer. His compositions are meticulously designed and constructed, lending an architectural quality to the works.

Ogunajo’s illustrative and meticulous approach to his compositions is particularly seen in Superboy (2014). The painting features a smartly dressed man, mid-stride on an asphalt road. Multiple arrow symbols as well as a cheetah in mid-leap (in the background) animate his forward movement. The background is also populated with diverse imagery—electrical drawings, a clenched fist, a crown, a lotus. A major quality in Superboy is one of unidirectional movement. The man’s self-assured swagger presents a sense of confidence in the journey despite the caution sign. We move with this man on this journey through the unfamiliar and yet-to-be-imagined.

Spirituality and the fantastical play significant roles in the exhibition’s consideration of the psycho-physical. Serpents, chimaeras, dragons, dismembered bodies and clowns populate the surfaces of Ogunajo’s canvases, creating dystopian scenes of the mythical. In Holy Grail of Vices (2017), a hybrid creature with the head of a goat and the body of a man sits cross-legged, surrounded by several icons, wild animals, mythical creatures, and graffiti-style text. Four pairs of arms jut out from the sides of the creature, each arm holding a different object. An extra pair of amputated limbs extend from its shoulders. The words ANCIENT TEMPLE MAGIC are shown boldly in block letters at the top of the painting. The inscription immediately brings to mind commercial images of mysticism and the occult. It considers the commodification of spiritual practice as an alternative for instantaneous remedies and results.

Text plays an important role here in defining meaning. Phrases drawn from advertisements of ‘quick fix’ schemes run vertically along both sides of the picture plane. Ogunajo points to the constant search for supernatural solutions to modern problems in contemporary Nigerian societies. Holy Grail of Vices is at once comical and tragic. We are amused at the list of improbable solutions to diverse problems yet are faced squarely with the socio-economic realities of the people as well as their hopes and aspirations. Phrases like ‘Business Boost’, ‘Win Election’, and ‘Instant Money’ give us a glimpse into a transactional relationship. A relationship one realises is necessitated by the growing rate of corruption and insecurity in Nigeria. In this context, religion isn’t just a means of engaging and understanding the metaphysical, it also becomes a near-final recourse for the fulfilment of wishes and desires.

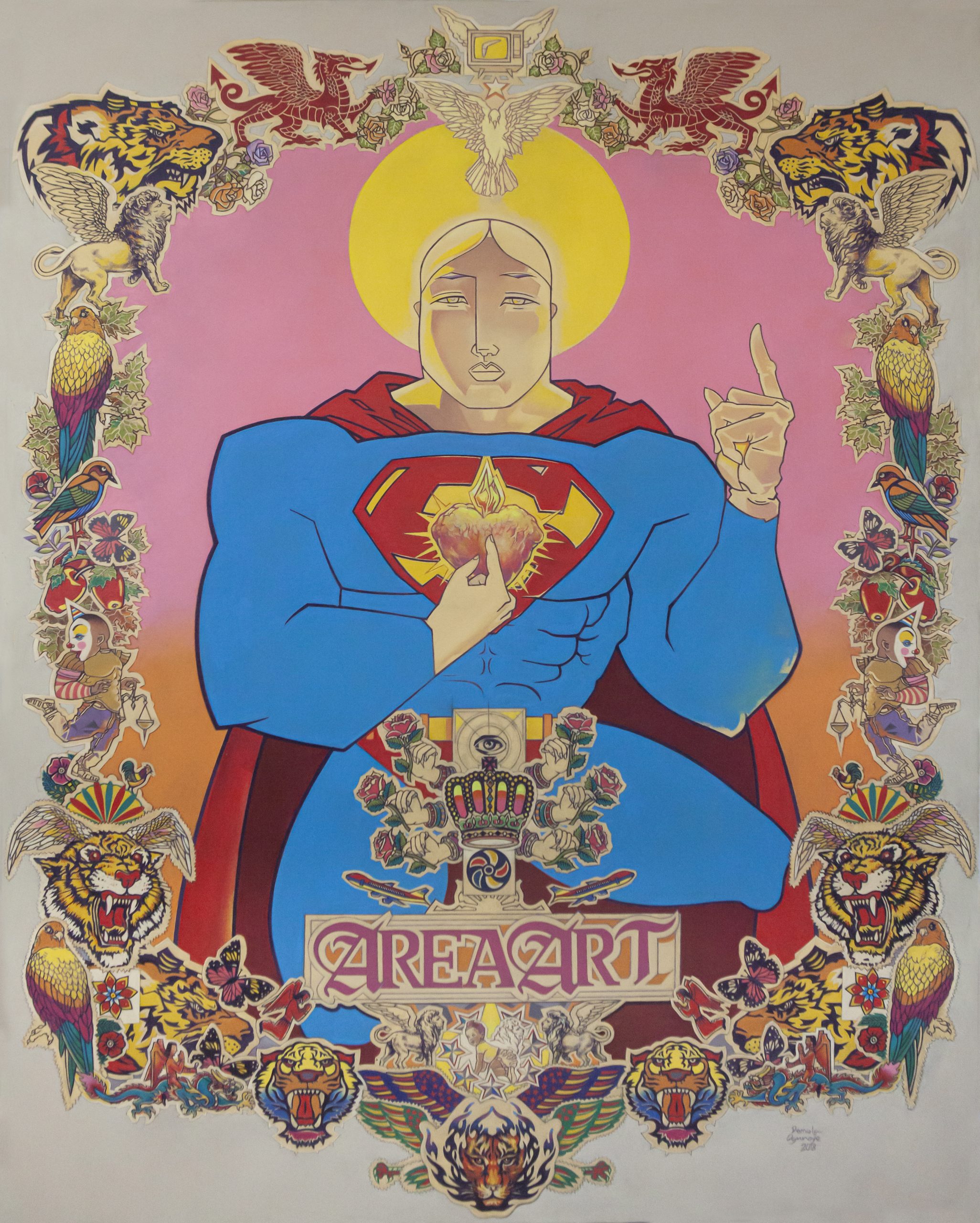

The works in Area Art not only give us an insight into the stylistic and compositional developments in Ogunajo’s practice over the years, they also present critical considerations on the structure of society, from the philosophical to the practical. His exploration of the human and the celestial highlights themes of enlightenment and divinity, collective consciousness and knowledge production. Area Banner (2018)—a work that ushers us into the exhibition space—shows a figure drawn from the D.C superhero character ‘Superman’ in a position reminiscent of depictions of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Roman Catholicism. The artist’s representation of the popular comic character as a divine being forms a vital introduction to the exhibition premise. In Area Art, images and objects from the physical and mundane are elevated into the spiritual realm. A transfiguration of sorts. The exhibition invites the viewer into an exploration of myth and fantasy and their relationship with social consciousness. By culling local graphic expressions from commercial buses, signages, murals and other utilitarian items and combining these familiar images with the otherworldly, Ogunajo renders the intangible and leads us onto new meanings.