Eric Gyamfi’s monochrome photos of female chiefs in Dagbon, northern Ghana, border on contestation – the fine line between photojournalism and art photography.

Chieftaincy in northern Ghana is quite different from what exists among the Akan people of the South. The Akan have, at least theoretically, both the male chiefs and the female queen-mothers sit in the state as co-rulers to receive homage. In the North, one of the two sits at a time to perform the chieftaincy duties. And it is mostly men, flanked on each side by other men, who sit in the state as chiefs.

This systematic process of elimination is a performance of power – if you are absent, your voice can quite easily be denied. This is what happens to the female chiefs in northern Ghana. The performance of chieftaincy duties is seen as an act of masculinity and an extension of male authority. This space has, however, also evolved as a place for women too, but often in the shadow of masculine performance. Even among the Akan – who, in theory, have the Queen-Mothers as co-rulers in every town – the women leaders are not members of the National House of Chiefs. In the collision of the nation-state and ethnic-state, the woman leader is left behind in a stroke of constitutional disregard. Though Ghana’s constitutional definition of a chief is gender-neutral, the practice is to accept the male chief into the House instead of the female.

Born in 1990, Gyamfi practises mainly as a photographer favouring monochrome images. His body of work includes documentation of alleged witches in Gambaga, northern Ghana, queer lives and spaces in Ghana, living arrangements of the floating population in urban spaces, and self-portraits exploring his masculinity and coming of age. In these series, Gyamfi shows an eye for exposing the hypocrisies of society by focusing on what society prefers to ignore.

In a previous conversation, Gyamfi, in reference to his earlier portrait series on queer lives in Ghana titled Just Like Us, stated that “the idea of erasure is scary”. That seems to be his ethos in creating – documenting marginalised lifestyles and spaces.

Gyamfi first came to know about the female chiefs in Dagbon through Alhaji Suleiman ‘Gonje’, a local Dagomba (Dagbamba) griot in Yendi, the traditional capital of Dagbon in the Kingdom of Dagomba. In Dagbon, the Islamic religion has been nativized. During the colonial period, Germany was administering Yendi. The British, wanting to break Germany’s power grip, founded Tamale, to the east of Yendi. Tamale, the so-called Islamic capital of Dagbon, flourished and attracted Islamic scholars who used it as their base. Women leadership in Dagbon does not only have to contend with native beliefs but also, perceived interpretations of the Qur’an by the Ulama (Muslim clergy). Upon ‘discovering’ the Dagbon female chiefs, Gyamfi abandoned his original plan of researching northern festivals and concentrated on them instead. In a photo exhibition in Tamale, Gyamfi’s monochrome photos find a home among others that explore life in northern Ghana.

Since 2008, the idea of contemporary art in Ghana has been to appropriate materials and use it as political currency. The exhibition space of the exhibition in Tamale was the former state printing house which was abandoned and has now been repurposed as an exhibition hall. This was the space that the exhibited photos interacted with, subtly critiquing Ghana’s failed postcolonial industrial agenda and also, the lack of presentation space for artists.

Photography in Ghana, as a form, was a silent accomplice of the colonial project. It was used to justify the ‘otherness’ of the natives and for evangelical purposes. The contemporary photographer should imagine the photographic form as a material, participants treated with compassion and handled with dignity. Gyamfi does that. The photos of the female chiefs are mounted in close proximity to the male chiefs as if it is a corrective gesture – a claim for equity.

In my earlier conversation with Gyamfi, I asked him why he shot Just Like Us in monochrome. He answered, “Black and white here is meant to create a kind of ‘pause’, a brief moment within which you are not sure if the work and its subjects (participants) are from this time or (this) geographical location. That pause enables people to go in slowly, and engage to find out when, where and who.” He added that the monochrome is meant “to create a temporary disconnection.” So, after exhibiting the photos of the female chiefs, I asked him the same question, this time, he answered, “I wanted to focus primarily on the power most of these chiefs exude. A lot of colour would be a distraction from this but there is also an opportunity cost here. Clothing and colours carry stories, history, etc. That was something I sacrificed. Someone else can take that on if that has not been done already.”

The irony of Gyamfi’s practice is that he uses disguise, that is the monochrome, as an instrument to engage his audience. As he brings the marginalised community to the fore, he uses the same technique that is often used to overlook them. This makes seeing intentional and a willing endeavour.

The female chiefs that Gyamfi photographed can broadly be grouped into two; ‘royal’ and ‘merit’ chiefs. Traditionally in Dagbon, certain skins (chieftaincy seats) are reserved for women only. These include the chiefdom for towns and villages such as Gundogu, Kpatuya, Kuglog and Shilin. There are other skins that are alternated between men and women. The occupants of the skin for women are sisters, daughters or granddaughters of Ya Naa, the overlord of Dagbon – making them royals. They are menopausal women though there is no rule that suggests that they should be. The most elderly is considered next in line of succession. Among the female-only skins, Gundogu Naa and Kpatuya Naa are the seniors, Gundogu Naa being the senior of the two. They get to sit on the Dagbon traditional council. Gundogu Naa, as the sister of Ya Naa, is the only one that can veto him. She is, however, not part of an arm of governance, and as such, gets to hear of issues when they have already been decided on. The Kpatuya Naa also does not have any voting rights on the traditional council. While the royal female chiefs are not practically powerful in the traditional council, they are in their respective communities and perform duties as any male chief will.

Dagbon in contemporary times has created more female chiefs based on merit. In some of these cases, women who are former Magarzias (women organisers) have been elevated to the status of chiefs. They are selected based on their service in their communities and track record of mobilising women. On the surface, it would seem as though there is a balance in power as these merit female chiefs could be appointed in places where male chiefs already exist, but that is not so in reality. These female chiefs serve at the pleasure of the male chiefs, as an extension of the male chieftaincy institution. Even though Dagbon tradition has evolved as a place for women leadership, its effective practice is hampered.

The book, Northern Ghana Life, which accompanied the Tamale exhibition, describes an encounter with a Gonja (another major ethnic group in northern Ghana) female chief. Whereas her male counterpart the Kpembewura’s palace was easy to find, the female chief’s palace was tucked away from public view. When asked about her weekly meetings with her male counterpart, she said to her interviewers, “But we are yet to be heard”.

The power of a female emissary, as an agent of Ya Naa, is deeply steeped in history. Heinrich Klose, the Police Commandant of eastern Dagomba when it was under German rule (1889-1916), wrote fondly about a Dagbamba princess who was Ya-Naa’s emissary in Kete Krachi. Klose’s plan was to gain the princess’ favour in order to win Ya Naa but her power was only superficial – a means to Ya Naa.

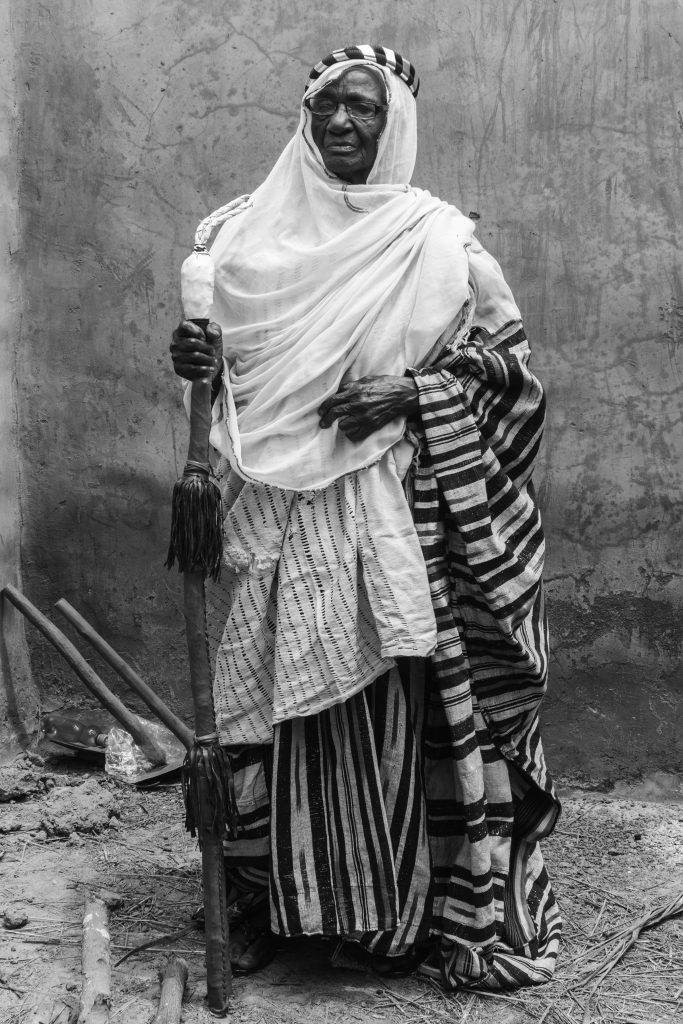

The portraits of the female chiefs as photographed by Gyamfi show them within the proximities of power and far off. They are mostly standing, supporting the balance of their bodies with walking sticks. The composition of the portraits in black and white hide a lot of details. The merit female chiefs maintain simple clothing – a wrap draping the lower body, a headscarf with the same pattern on the wrap, and a piece of cloth folded and placed on the left or right shoulder. The regalia of the ‘royal’ chiefs are either fugu, the northern Ghana smock, or a one-piece handwoven cotton cloth. Long, thick walking sticks, and with an assortment of woven leathers covering them, were used for the ‘royal’ chiefs while the ‘merit’ chiefs have ordinary walking sticks. The Gundogu Naa, Hajia Samata Abudu, is fitted in a hijab, a commentary on the close collaboration between the native tradition and Islam in Dagbon. Many of the chiefs seem to be in the twilight of their lives. They are photographed outside what would be their palaces as they look sternly into the camera.

This sort of reading of the portraits seems to be a parody of the situation of the female chiefs. They are present in the form, yet, they are absent in the performance and expression of power to a certain extent.

In 2013, NORSAAC, a local organisation in Tamale, published a photo diary on woman chiefs in northern Ghana. At the launch, a banner of the women chiefs hung at the rear of the high table. A group, mostly men, sat at the high table. Though the programme was about the female chiefs, none were seated at the high table. What Gyamfi’s portraits do differently is that the female chiefs are at the centre stage. It brings to the fore women leaders from a heavily male guarded society, documenting their presence. It gives them a voice and representation. These portraits challenge what is popular knowledge of women leadership in northern Ghana. When President Akufo-Addo was considering Hajia Alima Mahama, a woman from northern Ghana and an accomplished development worker, as his vice-presidential candidate for the 2008 elections, a section of the Ulama in Tamale issued a supposed fatwa on women leadership against her nomination. In the end, she was not appointed. In these portraits, we see Muslim women in leadership, even if it is not political.

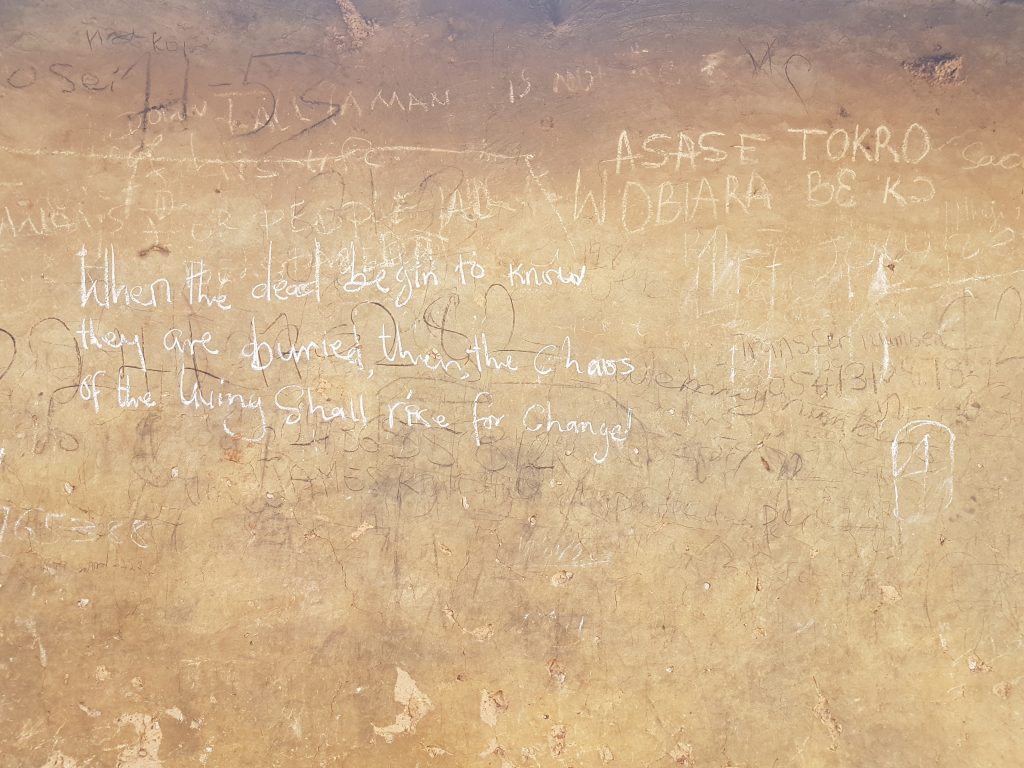

“I remember all their names and titles”, says Gyamfi, when asked if he still remembers the female chiefs. “I have the phone number of one of them, perhaps the one I was drawn to the most, Sanguli Upibor Chachaloni II Paka Dalafu. She was really interesting. A very gentle woman with undeniable charisma. She said I have a strong spirit. I had a good bond with her nephew, Joseph Dalafu. She gave me a lot of eggs to eat when I told her how much I love eggs. She also had something interesting written in chalk on a wall somewhere in her house, where I made her portrait. It read: ‘When the dead begin to know that they are buried, then, the chaos of the living shall rise for change.’”

Perhaps, these portraits would give rise to change, a restoration of the power that rightly belongs to the female chiefs.