Obi Okigbo is a painter and visual artist currently living and working in Brussels, Belgium. She grew up surrounded, first, by the work and personality of her father, Christopher Ifekandu Okigbo (1932 – 1967), the revered Nigerian modernist poet. His work has influenced poetry and intellectual discourse across the world.

Like her father before her, Okigbo continues to produce work that, according to her, assembles ‘poems’ or ‘connections’ of perception. Her process involves “building upon a fundamentally architectonic understanding of the world.” Okigbo says these are conceptual and, “like archaeological maps, they reveal through their layers the passage of time, movement, traces, and imprint techniques of layering realities.” More importantly, Okigbo’s practice evolves in different directions and forms depending on the chosen media: poetry, painting, or architecture.

In this conversation, we spoke about the rich foundation of her practice and using different media to express human and cultural conditions.

Obi, it’s good to be having this conversation with you. Thank you for making the time. I want to commend you on your work and projects. They have been brilliant. That said, I am hoping we can start with your exhibition Convergence presented at SMO Contemporary Art. The exhibition is a culmination of different bodies of work, a kind of self-documentation that draws extensively from history—personal and collective. I can see diverse influences and experiences inform the work—the artistic, the spiritual, the philosophical—making it an expansive dialectic. Aside from your father, who and what contributed to the emergence of these works and the discourses they begin? Could you describe this journey?

I’m the one to thank you for taking the time to have this conversation. I’m deeply touched by your comments above, how you have captured my essence after such a brief encounter.

Convergence spans over a decade of production and three major bodies of work. To fully answer your question, I’ll have to go back to my student days at the Architectural Association School of Architecture London in 1988-91. In 2001, I was approached to participate in a collective exhibition, Les Elles des femmes in Brussels. I drew heavily on my architectural background to produce my first artistic series, Casa Dolce Casa. These series of drawings and collages revisit my MA thesis research; mapping how people perceive the world, assign value to its parts and manifest them, focusing on Nomadic peoples in Northern and Southern Sudan. Casa Dolce Casa attempts to assemble poems or connections of perception; like archaeological maps, they reveal through their layers the passage of time, movement, traces, imprints.

This technique of “layering realities” recurs throughout my practice and evolves in different directions and forms depending on the chosen media. Building upon this fundamentally architectonic understanding of the world (light/shadow, rhythm, geometry & enclosure), I started making the shift towards a more conceptual means of expression.

Then in 2002-2007, I embarked on a journey to work on a series of oil paintings in conversation with my father’s poetry which I’ll mention briefly as this was a seminal passage that planted the themes for my work today. As I began to dig into the archives of memory, searching for clues about the poet and father that I knew so little about, I plunged into a realm of adventure that took me back to my childhood experiences in Lagos in the ’60s, and even back into the belly of memory itself.

My deep-seated love for fables & epic tales was revived; I became increasingly fascinated by our belief systems–the art and architecture left behind as silent witnesses of humanity’s aspirations. My horizons widened as I became acquainted with Mbari art and ideology in Owerri, Igbo-Ukwu sculpture, the poetry of Hafez & Rumi (from the 13th century), the writings of Joseph Campbell, Coptic art, ancient Khemet philosophy, Gilgamesh, the Mahabharata, and Yoruba art. All these left indelible imprints on my world of imagination and are referenced in the narrative encapsulated in the exhibition Convergence.

Using canvas as my fabric, I set about tentatively weaving these themes of transcendence and metamorphosis, looking for constants, mapping our collective consciousness through the re-interpretation of existing iconographic art and placing myself as the Protagonist. I’ve always been attracted to renaissance art & Flemish paintings from the 15th century. My approach to painting is that of an apprentice, and I turned to these same masters for everything I know about the craft (technique, composition, light, shadow, perfection). I study and learn from Giotto, Sandro Botticelli, Da Vinci, Caravaggio, Cy Twombly, Paul Klee, Van Eyck brothers, Rothko, Paul Gauguin, Frida Kahlo, Andrei Tarkovski, Joseph Beuys, even reproducing copies of famous masterpieces.

2008 marked a turning point in my painting when I encountered the ink paintings by ‘Oh-won’ Jang Seung-Ub (1843-97). As a craftswoman, I had been looking for ways to hone my skill. Oh-won guided me to the discipline of controlling the alchemy of indelible black ink, the brush stroke and water on absorbing paper that was incarnated in his work.

The ink on linen paintings in Convergence: Weaverbird, Watermaid, The Clearing, Ibeji, Jacob’s ladder, nous between the two, twilight moment in the wake of a dream & Yellow Melodies are evolutions and revolutions of the process of creating new narratives based on the most ancient of all—the eternal cycle of birth, death and regeneration.

This is remarkable. The French art historian Hubert Damisch notes that painting can be regarded as “traces of an activity to the eyes”. You’ve been influenced by several artists and quite significantly by your father, Christopher Okigbo. What has been the impact of his poetry on your work and career?

As mentioned earlier, 2002 is a significant point in my life. When I decided to illustrate Labyrinths and Path of Thunder, the first thing I did was visit Idoto, the village stream in Ojoto, my father’s hometown referred to in the opening stanza of Heavensgate.

Before you, mother Idoto

naked I stand;

Before your watery presence,

a prodigal.

I returned from my pilgrimage to the legendary stream repeating the Protagonist’s journey of obeisance and penitence. This pilgrimage and experience inspired my first major body of work. These oil paintings were displayed alongside the poetry of Christopher Okigbo and exhibited in the solo show Tapping into the Known at the Brunei Gallery in London in 2007. It marked the beginning of my vocation as an artist.

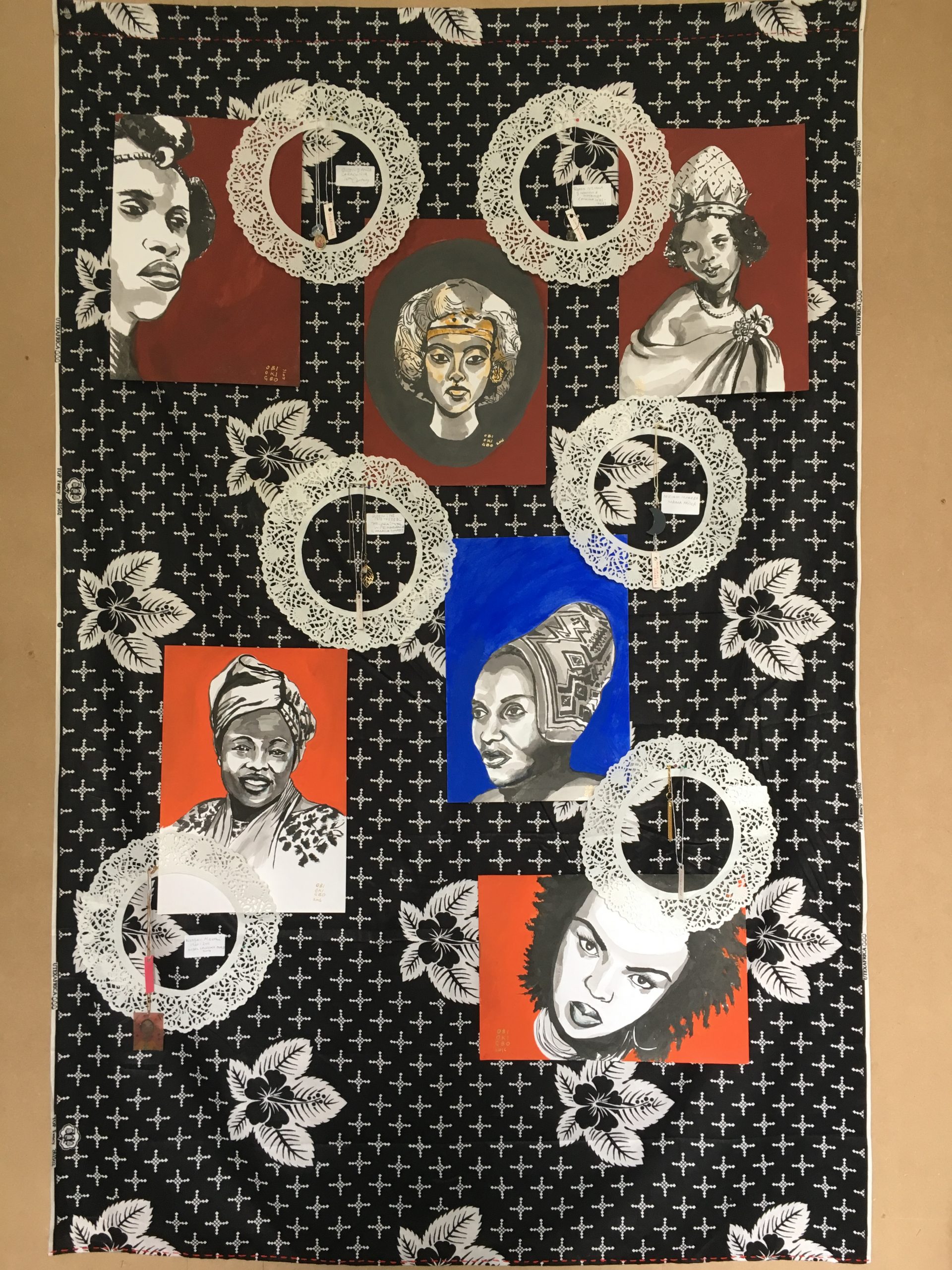

Discovering Indian ink painting in 2007 was an epiphany of sorts. I immediately started working on portraits as an entry point to develop my calligraphic skills. The initial collection was exhibited as an installation, The Last Supper, at the Brunei Gallery show mentioned earlier. The series has grown for over a decade, now incorporating pen and ink-wash techniques. The Icons and Mbari series shown in Convergence are actually part of an expanded piece Mystic Lamb, a life-size reproduction of the ‘Ghent Alter-piece’ or ‘Het Lams Gods’ polyptych by Hubrecht and Jan van Eyck (1425) that I have been developing since 2008. The complete installation consists of over 300 portraits of protagonists spanning 3000 years of African (hi)story. Inherently, this piece is an offering: a work of devotion to “those who have paved the way” so that we may shine. A celebration of collective memory, the archetypal quest for the self and the truth of our existence. I plan to show the finished piece in Belgium later this year, finger’s crossed.

In 2017, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Biafra/Nigeria war (1967-70), I participated in a series of events relating to the impact of the conflict on our present-day humane and geo-political condition. We kicked off with a group exhibition organised by NASUK (a collective of UK based Nigerian artists whom I’ve associated with for the last six years) at the annual Igbo Conference at Brunei Gallery, School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS. Then in June of the same year, I was invited to a conference with writers and artists organised by Olu Oguibe at documenta 14, public programs: parliament of bodies in Athens. I produced a new body of work Ode to Remembrance based on my personal experience and growing concern about the collective trauma and post-traumatic stress incurred by the war. Ode to Remembrance is a triptych – painting, installation & video evoking a ‘memorial site’ dedicated to the victims of this tragedy, advocating healing, renewal and regeneration. It was also my first attempt at filmmaking and performance.

It is fascinating to see the increasing use of multimedia in your work. Can you speak more about your choice of media and its overarching sense and impact on the outcome or type of work you create?

When it comes to painting, my choice of materials – ink, oil, pen, canvas linen, paper, silk – depends on the subject and my mood, which comes in cycles, like seasons. Each material has its inherent properties, so when engaging a new idea, I experiment with the tools that correspond to my sentiment at that moment. I’m equally passionate about oil on canvas or ink stains on linen, and I’m always in awe of the infinite possibilities of a few colours when handled with skill and intuition. Although my principal practice is painting, I’ve started incorporating spoken word and performance pantomime into my repertoire. For example, in 2018, I produced a short film, Ode to Remembrance, that was mentioned earlier where I worked closely with Belgian actress, musician and poet Maia Chauvier in a duo act, performing a symbolic “rite of conciliation” for the lost souls of the Biafra conflict. This collaboration involved poetry recitals, acting, and filming, which opened completely new avenues of expression for me.

My current project is to assemble the audio-visual archives (interviews, photos, manuscripts, notes and essays, etc.) that I’ve accumulated over the years under one roof. This research compiling legends and histories of Afrikan heritage will ultimately become the script for a film. I love Nollywood epics, so it was a natural choice and a great opportunity to plug into this thriving industry.

It will be interesting to see the relationship and interaction of these diverse materials and processes! What other narratives are you taking from Convergence into this new project?

A common thread that links the collection of paintings and drawings shown in Convergence is this notion of collective memory. In the portrait series, I touched on my interrogation regarding our African stories; everyone needs someone to look up to. Who are our heroes? I want to refine these narratives about restoration and transmission. As an artist, I feel a deep-seated responsibility to pass on the beacons of light to the next generation to inspire future heroes.

Who are these next generation(s)? Do you think your work communicates the complexity of your research and process effectively to younger people who encounter it?

Who are these “next generations”? Our children, our future. I often collaborate on projects (ranging from graphic design to video editing or even working as a painting assistant) with students and art collectives working with young artists. The presence and input of these young ones infuse a refreshing perspective to the outcome. Also, I was fortunate to have participated in an Artists in Residency program in Thailand some years back. There were artists from different parts of the globe and various disciplines such as sculptors, dancers, designers, all working together. The feedback and exchange during this program were indeed very enriching.

The huge un-truths and omissions in the history of the African continent awakened me to the urgency of collecting, archiving and narrating our own stories. The line-up of portraits in Mystic Lamb is testimony to this new and dynamic repertoire. I plan to publish this work with detailed biographies of the personalities portrayed together with essays from scholars in Nigeria and abroad. I like collaborating with art collectives, artists and working directly with all disciplines in the creative field. These exchanges have flourished into manifold forms of expressions, but most importantly, they have forged lasting relationships. I’ve been increasingly involved in spoken word and poetry performances linked to the work of my father, Christopher Okigbo. Just recently, I participated in an off-beat poetry publication by Koku Konu at CIA Lagos and poetry performances for the Three Sisters (W)RAP Party by Inua Ellams (poet, playwright, performer, graphic artist & designer) at the National Theatre, Lagos; ‘The Africans’, a radio play in 3 acts by Christian Nyampeta at WEILS, Brussels despite the endless lockdowns here in Brussels.

I don’t know if my work is relevant to society. We have to wait and see if it stands the test of time. But I do know that it is essential for my personal development and my conscience. If I’m to be remembered, I hope it will be related to the quality of my craft; a Master Painter! If my work can induce an emotion, if one can find a reflection of the self, if I can inspire a fellow painter, I will be well pleased.

Let’s reflect on your current activities, for instance, the Les Orages exhibition. Perhaps, you can also speak to situations, such as practising in this time of Covid-19 and the global lockdown?

It’s been a devastating year on all levels for most people. I had a couple of exhibitions planned for 2020 (which is a big deal for me), but both were cancelled or rescheduled. Also, I make a living from architecture and interior decoration commissions, which all came to a halt too, so it’s been a struggle financially. Despite these physical and financial restrictions, we all had to adapt our ways of working and communicating, and from these, surprisingly, new projects have developed. I’m participating in the exhibition Les Orages that opened in Brussels, showcasing mainly locally based artists. It is one of the positive outcomes from the restrictions in these Covid-19 times.

With regard to production, though, my routine didn’t change much since working in the studio is quite a solitary affair. Who knows what compels me to go every day to come face to face with the unknown. To unlearn my preconceptions, to re-invent myself each time. Painting is like a prayer that summons the land of my ancestors, my hopes, desires, regrets, failures, my strength, my expertise, my belief & my favourite things. I feel fortunate to have a vocation that piques my curiosity and pushes me to do the best I can.

I’ll finish with a few lines from a song by Linton Kwesi Johnson:

If I was a top-notch poet

Like Chris Okigbo

Derek Walcott

Or T. S. Eliot

I would write a poem

So damn deep

That it bitter-sweet

Like a precious

Memory

Will make you weep

Will make you feel incomplete

Like when your lover leaves

And though defeat you concede

Still you beg and you plead

Till you win a reprieve

And you’re ready for rock steady

But the music is done already

Still

In the meantime…

–

Jude Anogwih is a visual artist living and working in Nigeria and the United States.