In recent history, around the world, we would be hard-pressed to find an event that has had more of a marked universal impact than the COVID-19 pandemic. The global outbreak of the virus has been extremely deadly, taking the lives of over 400,000 people [at the time of going to press] worldwide, while simultaneously crippling the economies of numerous countries.

The number of infections in Africa is rapidly rising [over 150,000] and the number of deaths attributed to the infections is equally on the increase [over 4500]. Medical experts predict that the virus will remain a global threat for a long time.

In what appeared to be synchronised fashion, governments across the globe tried to counter the pandemic by instituting strict short-term nationwide lockdowns as the principal measure, to curtail the virus from spreading voraciously. Although this strategy saved many lives and relieved pressure on healthcare systems, the implementation of these lockdowns brought with it some expected adverse effects on economies of many nations and its citizens. In some instances, economic activity came to a grinding halt with many sectors of industry and business slowing down or stopping their operations completely. This came with massive job losses, a phenomenon that has negatively impacted the livelihoods of millions of people around the world.

“This pandemic has flipped the entire world and given us food for thought, new ways for seeing things and living…”

Stacey Gillian Abe

However, the interruption in economic activity has allowed governments and enterprises to readjust their functions to suit the precarious conditions of our time. Across many industries organisations have had to migrate their systems to the digital sphere and strive to establish online visibility and presence. Thus, many sectors that constitute significant contributions to national economies have scrambled to readjust their processes to be commensurate with the tectonic shifts currently reshaping global capitalism.

The global art and cultural sector is one of the many industries that has been severely hit by these crises as the art-ecosystem undergoes major structural challenges during this period.

South African artist and entrepreneur Banele Khoza is among those whose personal and professional ventures were abruptly upended by the virus. In April he was due to have two solo shows in the Netherlands and Belgium, respectively, and participate in a fellowship program in New York.

As the founder and owner of his own gallery in Johannesburg, BKhz, Khoza says he was also planning to take the gallery to Paris ahead of the fair season in November. All of these plans have now been postponed and moved to 2021.

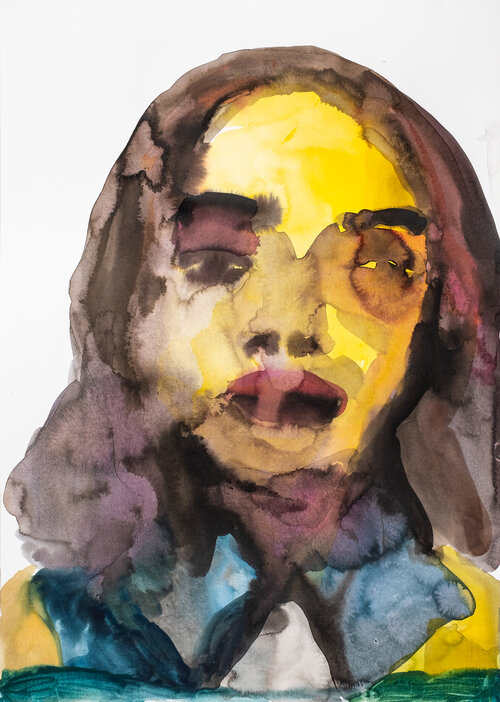

Ugandan artist Stacey Gillian Abe had upcoming shows on the continent and abroad before the pandemic induced lockdown hit, maintaining: “The lockdown has indeed affected a few upcoming group and solo exhibitions meant to happen within the African continent and abroad.”

Having suffered an initial shock at the beginning of the lockdown, art industry players are gradually finding their feet once again. This can be attributed to their proactive response evident in the considerable scaling up of infrastructure on the internet. Subsequently, in the past two to three months there has been an unprecedented eruption of business on the internet. In the frenzied activity of the art market to adapt to the changing times, we have witnessed an infusion of digital viewing rooms and regular Instagram Live conversations between stakeholders in the art world.

Interest in engaging with artists’ work has intensified as people seek artistic interpretations of the complex emotions, thoughts and experiences that speak to the human condition at this time.

“This pandemic has flipped the entire world and given us food for thought, new ways for seeing things and living,” Abe says. “Now as a united human race in this tragedy, I would like to see fewer individuals and more collaboration. Fluidity in organisational and institutional art structures…and elements of division like race, class, borders eventually fading out.”

Based in Marrakech, Houda Terjuman’s work speaks of migration, exile, displacement, the human search for a home, and resilience. Domestic objects such as chairs, tables and luggage are usually depicted in her paintings in the middle of a forest, describing the ways homelands are abandoned in the search for somewhere new. Her work attempts to show us how these objects are the only things that connect us to our homelands and host countries. Because they are the memory of where we come from.

“During the lockdown, I have been doing the inverse. I have been putting in walls [in her work] that are like our homes, and nature has been coming inside.” She adds that “it is always about nature, which we have to live with and we have to have a harmonious relationship with. We have to let it in our homes and our lives.” She states that for her “a home is not the country where I live but the place where I plant my roots.”

Terjuman has taken full advantage of the surge in IG Live conversations. She tries to join in and listen whenever there is a talk by an artist, institution, or gallery, observing that taking part in these conversations “is as if we are watching an exhibition.”

Nengi Omuku, whose work includes both paintings and sculpture, concurs with this opinion and claims that the art world has been somewhat democratised by the events of the past few months. Based in Lagos, she agrees that “with the proliferation of ‘viewing rooms’ and virtual exhibitions we can get a proper sense of art from all over the world. The global lockdown has helped us see more art and I hope that stays the same when the world is back to normal!”

For many people, this period of pause has provided much-needed respite from the usual frenetic pace of things. For artists, solitude is a state that can be useful to cultivate for themselves in their practice. Omuku says this has been very beneficial for her. “Lots of new ideas have come recently. I think the major influx of ideas has come primarily from the silence and solitude I’ve had to have. It’s all gotten very dark thematically unfortunately but I still feel inspired everyday and it has helped to keep me from getting depressed about everything.”

Likewise, Abe’s practice has also profited from the pause in activity as she experiments with forms. She expressed that: “ This lockdown unlocked many creative possibilities…I have been painting a lot, now you must know the painting was on halt for a few years[…] about four. What excites and scares me about this,” she further remarks, “is finally materialising concepts I wouldn’t normally pull off entirely in front of the camera, through my photographs without distorting the photographs altogether. I am not sure how the world is going to react to this dimension in my work.”

It has undoubtedly been a tough time for everyone, but many are reasserting the need for art through these increased digital interactions. “We are the mirror of society and healers at large,” says Khoza reflecting on the role of the artist in times of crisis. The role and importance of the creative arts have shone outward during this time, with people being home needing solace and entertainment. A lot of the introspection society has been doing is at the service of artists and makers of this world. However, despite this, artists find themselves amongst the most vulnerable during this moment.

It will take the world quite some time to adjust to these new changes. Though the adaptation is taking its toll, there exists during this daunting moment, a speckle of hope.

The time has also proved useful for those interested in learning. Nigerian artist-photographer Stephen Tayo says he has used this time to relax and show gratitude for the life he has developed for himself over the last four to five years. He has also been reading a lot and taking copious notes in the process. “I have been reading about my old professor when I was in uni,” he says. “Her name is Professor Sophie Oluwole. She has a book about Socrates and Ọ̀rúnmìlà, where she expands on the canon of African philosophy.”

“There is this conversation about what is known as African philosophy is based on mythology, so it doesn’t stand as philosophy. She stood her ground and said that there is a lot of comparison between Socrates and Ọ̀rúnmìlà. I truly find that interesting for where I am as an artist when you are carefully trying to curate your work.”

Tayo says he has managed to ground himself and his practice through Oluwole’s writings, especially during this fast-paced period of social media and even more so in the last few months as the relationships we have with our technological apparatuses have intensified.

The impromptu relocation of the world into the fourth industrial revolution has left swathes of the world’s population of disadvantaged people out of this movement, unmasking much of what is wrong with the global capitalist system. Noting this, social analysts have commented on the ways socio-economic inequalities have been exacerbated. Journalist P. Sainath has been vocal on this matter in India, saying that the lockdown has revealed the corpse of neo-liberal policies and the disparities that exist beneath its progressive veneer.

Asked about how she sees inequality manifesting during this period of a pandemic South African artist Lungiswa Gqunta says “countries have revealed themselves in terms of the resources that get provided, who gets provided with those resources, and how quickly they get provided.”

Gqunta acknowledges that these realities existed before the pandemic. She explains that rather than having money and resources directed to those most in need, the government is more concerned about the economy and how to maintain small businesses, rather than the well-being of communities that are at an economic disadvantage.

“Everything is met depending on what areas,” she notes. “Because we are living in quite segregated ways, some areas were well equipped beforehand. They got everything they need but still, most responses start in these privileged areas and then trickle down to your townships and locations.”

Cape Town-based photojournalist and documentary photographer Barry Christianson has been documenting what is happening on the frontlines in the fight against the virus as the primary local freelancer for the news media organisation New Frame.

As well as taking pictures of anaesthesiologists working at the Groote Schuur Hospital, Christianson has found himself engaging in more conceptual concerns with considerations about the mood and writing style the photographs call for. His process has slowed down significantly, he says, and he has started giving more consideration to the final product.

During this period Christianson has also documented the lives of the homeless in the upper-class suburb of Seapoint and the travails faced by queer African refugees and asylum seekers due to the prejudices they face in Cape Town.

The global pandemic has highlighted many things that are wrong with our current systems of political and economic governance. There has, however, been an outpour of solidarity and aid coming from different sources. South Africa, for example, has the Solidarity Fund, a platform for the general public, civil society and the public and private sector to support the people most affected by the virus and numerous artists form a huge part of this cohort. While in Morocco, the Fondation Nationale des Musées (National Foundation of Museums) has established a COVID-19 relief fund to support sculptors by buy purchasing their artworks for museums across the country.

Unfortunately, only a small fraction of artists get to procure such funds. As many people working in the art world do so on a freelance commission basis, artists have found themselves to be among the casualties of the shift in the world economic order.

It will take the world quite some time to adjust to these new changes. Though the adaptation is taking its toll there exists, during this daunting moment, a speckle of hope. It resides in the life force and imaginaries of the artists who make the world a more habitable place. While the world waits for a vaccine to emerge, we can look towards these creatives to find the beauty in the momentous struggles.