Yetunde Ayeni-Babaeko’s White Ebony sheds light on albinism in Nigeria.

A girl, ten or maybe eleven years old, is seated at the front of the class. Her translucent grey eyes dart back and forth, trying to keep pace with the teacher’s hand as it scribbles notes on the board. Still, the letters, hazy, remain elusive to her. She peers into the note of her seatmate as an alternative. Easier than her previous struggle, she begins to write until her host has to turn over a leaf. She lets out a sigh in resignation, knowing this would be another space in her notebook to be filled at a later time. This is a recurring experience for one of the twenty-four subjects featured in “White Ebony”, a photography exhibition focused on people with albinism, by Yetunde Ayeni-Babaeko.

“White Ebony” is not only a commentary on discrimination. It is an ode to the human form and its diversity.

Born in 1978 to a Nigerian father and German mother, Ayeni-Babaeko knew what it meant to be part of but not exactly belong to a people, because one lacked the right skin colour. Stemming from a long-time interest to explore the issues faced by people with albinism, the photographer worked closely with The Albino Foundation in Nigeria for more than a year. Communication with the albinism community began in 2018 over sit-downs and intimate conversations that spanned many months. Discussions were mostly recounts of their attempts to fit in, and the struggle for acceptance from society. They, however, thrive by depending on one another in their community.

“The first time I saw a person with albinism was in Nigeria.” said the artist. “Their colour stood out and I could not help looking at them longer than necessary. I immediately felt a kind of connection because here was a person who, like me, did not have the “right colour” to blend in.”

Drawing from her training and years of professionalism in advertising and fashion photography, Ayeni-Babaeko, through lighting and composition, portrayed people with albinism in a new light, reminiscent of classic paintings done by Renaissance and Baroque artists in Europe. A style she was reminded of by the distinct complexion of their skin. In particular, she reimagined and interpreted Johannes Vermeer’s ‘Girl with the Pearl Earring’ as ‘The Girl with the Blue Scarf’ and Edgar Degas’ ballet dancers as ‘Swinging Through Life’.

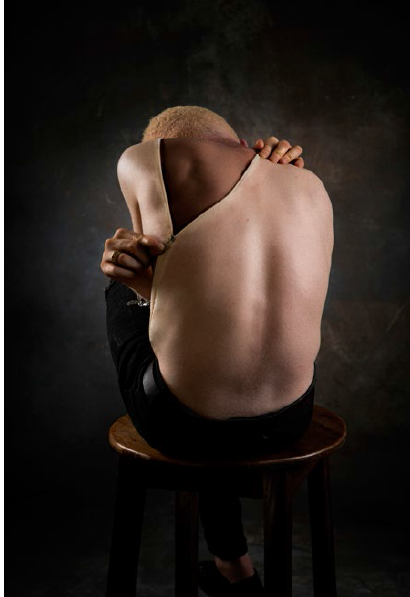

With clever use of props, costume, make-up, and brilliant photography techniques such as multiple exposures, layering, and collaging, these subjects remain alive within the frames. In their stillness, whether they sit, stand, bend, lie or crouch, they compel the viewer to not only acknowledge the beauty in the unconventional but also, to confront their biases and admit to an undeniable truth – they are us.

In “White Ebony”, the title piece for the exhibition, a lady dressed in tulle and voile stands with a poise – with one foot on the ground to hold her weight and the other anchored on a chaise lounge, her disposition is both strong and delicate. This vibe is similarly encountered in “In the Dark”, but with a fierce look from the girl adequately perched on a stool, her light brown hair standing out in a fro.

Ayeni-Babaeko, through lighting and composition, portrayed people with albinism in a new light, reminiscent of classic paintings done by Renaissance and Baroque artists in Europe.

The family bond is also strongly captured by the artist in this series. Works like “Mother with Daughters”, and “Twins” show a familial tenderness that is tinged by a delicate fragility that is often rarely publicly expressed in our society. “Protector” is another work that conveys a core significance of family. A mother, armed with a rod and a shield, defends her children from the metaphorical sun, represented by the studio light shining bright above them.

Melancholy and pain are most palpable in “The Truth”. It is reflective of the burden people with albinism all share, the message they have been screaming but society has been tone-deaf to, that despite their skin colour, they are here, they belong and they are Africans in their core.

“White Ebony” is not only a commentary on discrimination. It is an ode to the human form and its diversity. With this body of work, Ayeni-Babaeko portrays people with albinism with regal elegance, placing them high above prejudice, biases, and myths. She has expanded the stage of what is possible for this group.

At the opening of the exhibition, the air was charged with excitement when the subjects walked in to see themselves portrayed in photographs on the wall. “Taiwo is that you?” his girlfriend asked with awe in her voice. Taiwo was struck with disbelief. They both stood in front of the work “Secret Wishes”. It took some time but he answered, with a wide grin on his face, hands akimbo and with a confident nod.

“Yes! That is me.”

All images courtesy of SMO Contemporary Art.

The exhibition, White Ebony, is open till July 19, 2019, at Temple Muse, Victoria Island, Lagos. Click here for more details.