To air one’s dirty laundry in public is to be without shame, to not concern oneself with other people’s perception of what is shameful and how to respond to it.

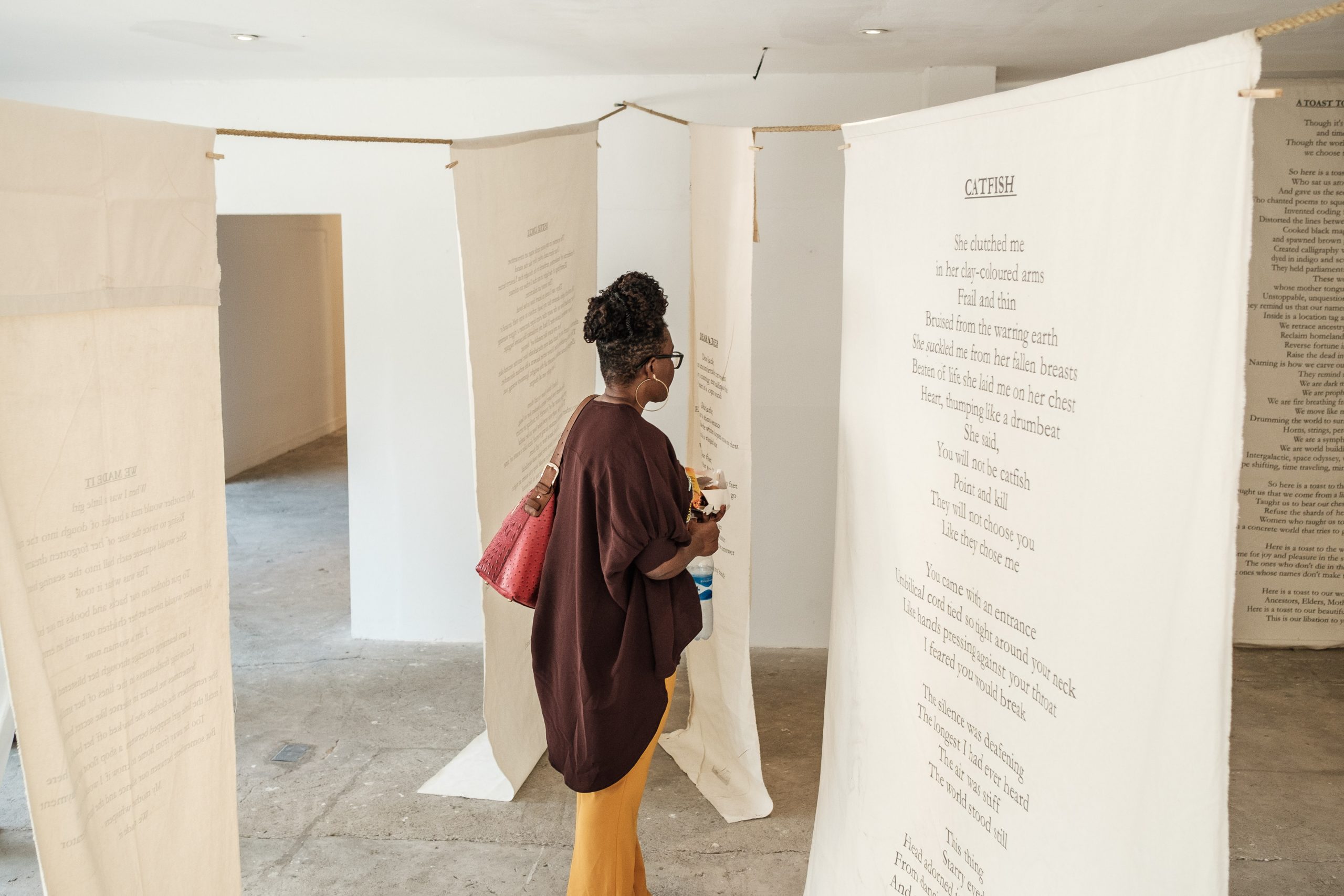

Deconstructing shame is at the core of Wana Udobang’s work. She invites us to examine closely what we consider disgraceful, why it is so, and what is left when we let go of the notion. This interest takes on a different, more tangible form with Dirty Laundry, a three-day event of installation and performance titled after her first spoken word album. It interweaves personal histories, familial complexities, and gender-based issues. Stories some strap to their chests or only relay in lamentable whispers are out in the open and central to the works presented.

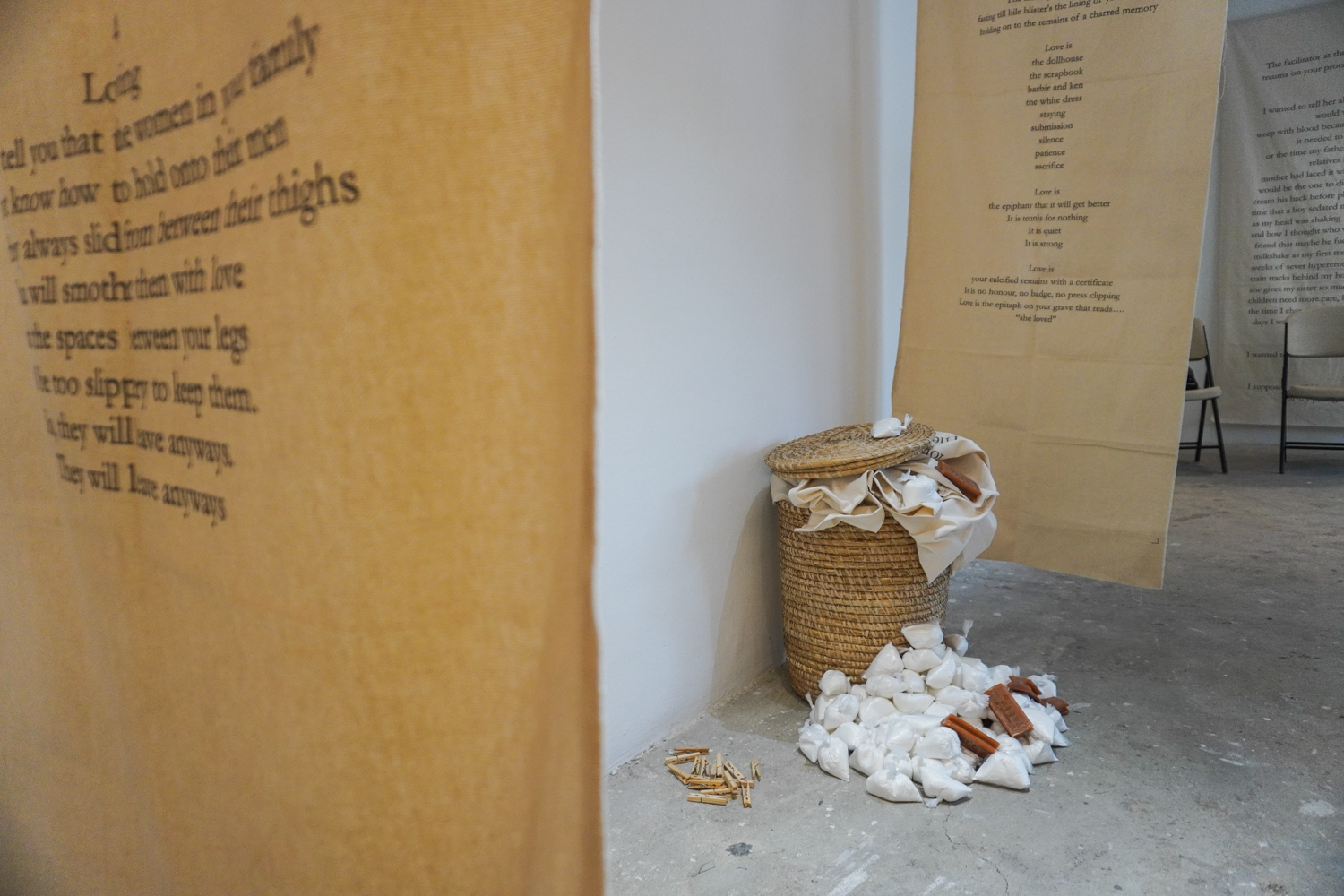

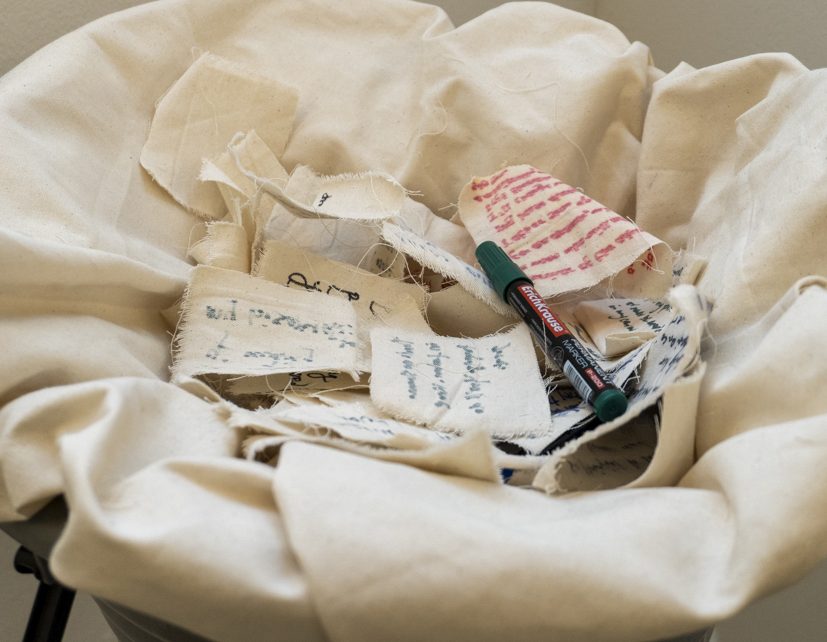

Everyone who opens the door of A Whitespace Creative Agency enters a world of almost white linen fabric covered with poems hung on clotheslines. On the first day, women sit in corners washing clothes in large basins filled with white lather as Udobang’s passionate and magnetic voice filters through the video installation of various poems. Instructive lines like, “if the pain gets too heavy, make sure you open your mouth and spit it out”, fill the space.

In her poem Thick Skin, the poet narrates being in a writing workshop where the facilitator said a protagonist’s story shouldn’t be ridden with trauma because their life would be deemed implausible. The poem goes on to detail moments of emotional and psychological trauma. Picture this: a father who suspects his tea has been poisoned gives it to his daughter to drink so that at least he won’t be the one to die. It’s no wonder “families are everybody’s first war,” Tola Rotimi’s poignant sentence from her essay “We Need to Talk About Snails” rings true for many. When your first and primary encounter in the world is responsible for the shame you spend the rest of your life trying to outrun, learning that your existence is, in fact, plausible is incredibly difficult but liberating work. Many years later, the daughter is here to tell stories about how she didn’t die—not from the tea or swift tongues that spill poison at her body—and how she’s living, thriving, reaching out to girls and women with the courage to walk their own path of freedom.

In presenting Dirty Laundry, Udobang’s major expectation is that the work connects with each person where they need it the most. “The work will hit everybody differently,” she says. “I’m asking you to sit with your discomfort.” Udobang herself has never been one to shy away from difficult, uneasy conversations. As one of the facilitators at a women-only workshop in March, she told the participants to pick a partner and look into their eyes. The two-minute exercise seemed to stretch into infinity, according to some of the participants. What did you see? Udobang later asked. How did you feel? Many admitted they felt naked, as though being probed, all their secrets in the open. It’s possible to go through decades in this world without spending, say, five minutes to look, really look at one’s image, and sit with the discomfort that ensues. “I don’t have any secrets; you can’t shame the shameless,” Udobang says, sitting on a bench in front of the poem titled Dear Father—a quiet plea, a painful shedding, a demand rounding up in a question—“Father, why did you stop holding my hand?”

Curated by Naomi Edobor, the installation and performance gathering is part of a larger conversation on healing. Udobang’s second and third albums, In Memory of Forgetting and Transcendence, explore this theme even deeper. During the panel session on the second day of the installation, the anchor Folu Storms brilliantly engages the four panellists—Wana Udobang, Itoro Eze-Anaba, Onyinye Onyemobi, and Jumoke Sanwo. They share insights on how people are socialised into violence and the importance of personal and collective work in creating the future we want. Sanwo, curator and founder of Revolving Art Incubator (RAI), emphasises that artists need to be more conscious and careful in portraying victims of sexual violence. “In working on violence, there’s a tendency to retraumatise the victim. Do you even have to photograph them?” The speakers also highlight the importance of educating children about their body and their rights. “We collectively fail minors,” says Eze-Anaba, founder of Mirabel Centre, a sexual assault referral centre. “There’s a lot to unlearn and relearn. So many factors enforce the patriarchy and we all contribute to it.”

“Today, all the dirty laundry comes down,” Udobang writes on her Instagram page on the third day. Hours later, words people have been reading in ink would come alive from the mouth of the poet. These are poems that, despite the depth of their sufferings, do not call out for pity. Instead, they say I can be a voice in your head, reminding you that you’re invaluable too, that you matter as you are. To Udobang, the project is about reclamation. “Liberation is my goal,” she says. “And it’s a practice. Every day I’m practising a life that is about personal freedom. Maybe someone sees it, and they are inspired in some way or they are forced to liberate themselves.”

Dirty Laundry interconnects the many ways the body absorbs and remembers grief and how it finds relief. These poems, these words offer means to crystallise self-love and personal revolution. Living an expansive life is crucial to Udobang and she urges everyone to do the same in their own lives. And this is why “if the pain gets too heavy, make sure you open your mouth and spit it out” is one of the many illuminating lines that will stay with the attendants for a long time.

–

Kemi Falodun is a Nigerian writer, journalist and editor. Her writing explores mental health, intergenerational complexities, social justice, and the intersections between private and public memory. She’s also interested in culture and writes about art, photography and film.