How should we, Africans, address the problems of xenophobia and ‘Afrophobia’ in the days of ‘Black Lives Matter’?

Woe to the Africans,

For taking our jobs

Curse to these foreigners,

For sleeping with our women

To hell with these migrants

Who infect our children with drugs

As our townships are bleeding.

From: Ayọ̀ Akínwándé, “No, Xenophobia”, 2019 (Unpublished).

Someone recently said to me in a conversation, “How do you unfuck what has been fucked? Africa is fucked!” In that instance, and in the context of discussing the xenophobia crisis in South Africa, one could agree that indeed the continent is a conglomerate of doomed realities.

In the build-up to the general elections in South Africa this year, President Cyril Ramaphosa, during one of his campaign speeches about “foreigners” said “Everybody just arrives in our townships and rural areas, and set up businesses, without license and permits. We are going to bring this to an end.” Election campaigns are said to be poetry, while governance is prose, or drama, as it has manifested in recent times. Rallying the troops, getting the votes, all are part of a political playbook that is tossed at the electorate at every election period.

The clampdown on “foreigners,” those said to be “operating illegally” isn’t entirely new in South Africa; these raids are sometimes accompanied by looting and violence. But then, who are these accused “foreigners” who steal the jobs and women of South Africans, and deal in illegal drugs? Who are these people often blamed for many of South Africa’s woes and social ills? Sadly, these “foreigners” are African nationals living in South Africa and only about 2.8% of the population. They are the “other,” or in Trumpian words the “illegal aliens.”

Achille Mbembe refers to these clampdowns as the “hunting season”. He states further that “No African is a foreigner in Africa! No African is a migrant in Africa! Africa is where we all belong, notwithstanding the foolishness of our boundaries. No amount of national-chauvinism will erase this. No amount of deportations will erase this. Instead of spilling black blood on no other than Pixley ka Seme Avenue (!), we should all be making sure that we rebuild this Continent and bring to an end a long and painful history — that which, for too long, has dictated that to be black (it does not matter where or when), is a liability.”

Susan Tolmay of Amnesty International South Africa, in her article on the Daily Maverick, asks “How is it that in 2019, 25 years after the first free elections with our history of struggle for human rights and end to discrimination in all its forms, we are treating people so inhumanely, in ways our struggle icons fought against? What does this say about us as a nation?”

What these xenophobic attacks have revealed is that the transition from apartheid into democracy, including the journey through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which was supposed to heal the wounds of the apartheid era, was not quite successful. The wave of irresponsible statements by those in the position of power, which tacitly endorses the violence, only shows the political class, predominantly Africans, is complicit.

Although the entire African continent is grappling with the debris of a colonial past, South Africa seems to be more troubled as the repeated xenophobic attacks show. Because, how can one make sense of these attacks on African “foreigners”? The freedom of the country from institutionalised white oppression was made possible by the combined efforts of different African countries that saw the liberation struggle in South Africa as theirs. But it seems that as Nelson Mandela walked into freedom in 1990, and was subsequently elected president in 1994, the African brotherhood vanished. South Africa has only cared about South Africa.

Africa is no longer a country. One that was besieged by the ‘white man.’ We are in the Post-Colonial and Post-Apartheid eras. It is now a continent. One that is being run and ruined by new oppressors, who have mortgaged the future of its young population. All that is left of Pan-Africanism are empty rhetorics, diced into irony. The irony of applying for visas to pan-African conferences on the continent, and being a foreigner on the continent.

If white on black oppression is not acceptable and proclaiming that ‘Black Lives Matter,’ is crucial at this point in our human history, how then should we deal with Xenophobia or its more shameful sibling ‘Afrophobia’? Is discrimination and hostility toward a familiar ‘other’ more acceptable or less shameful than hostility toward a different ‘other’? Cameroonian art historian, curator and writer, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, weighs in on this when he says “The issue being that most of our South African – just like many of our African American – sisters and brothers have bought into the idea of the neoliberal capitalist dream that positions wealth and a certain notion of nationhood beyond any kind of solidarity to any form of Africanness or Blackness. And when Blackness is evoked it is reduced to “South-Africanness” or “African-Americanness”.

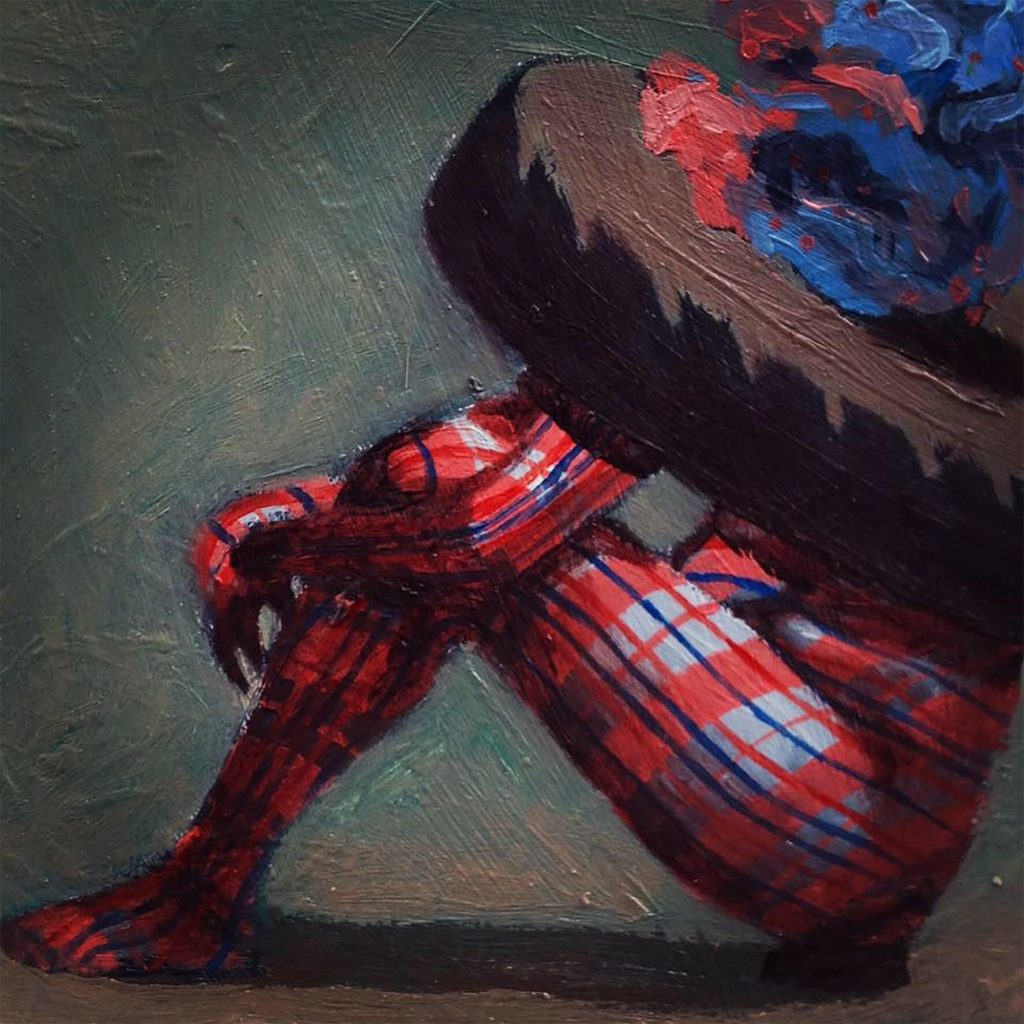

But how did we get here? How did we enter into this dark abyss of hatred and division? How did we transition from our brother’s keeper to our brother’s slayer? While watching the horrific footage from the recent xenophobic attacks, I knew they looked familiar—violence on black bodies by black people. The alleged witch that is set on fire, the alleged thief that is set on fire, the countless news of jungle justice system, the images flash through.

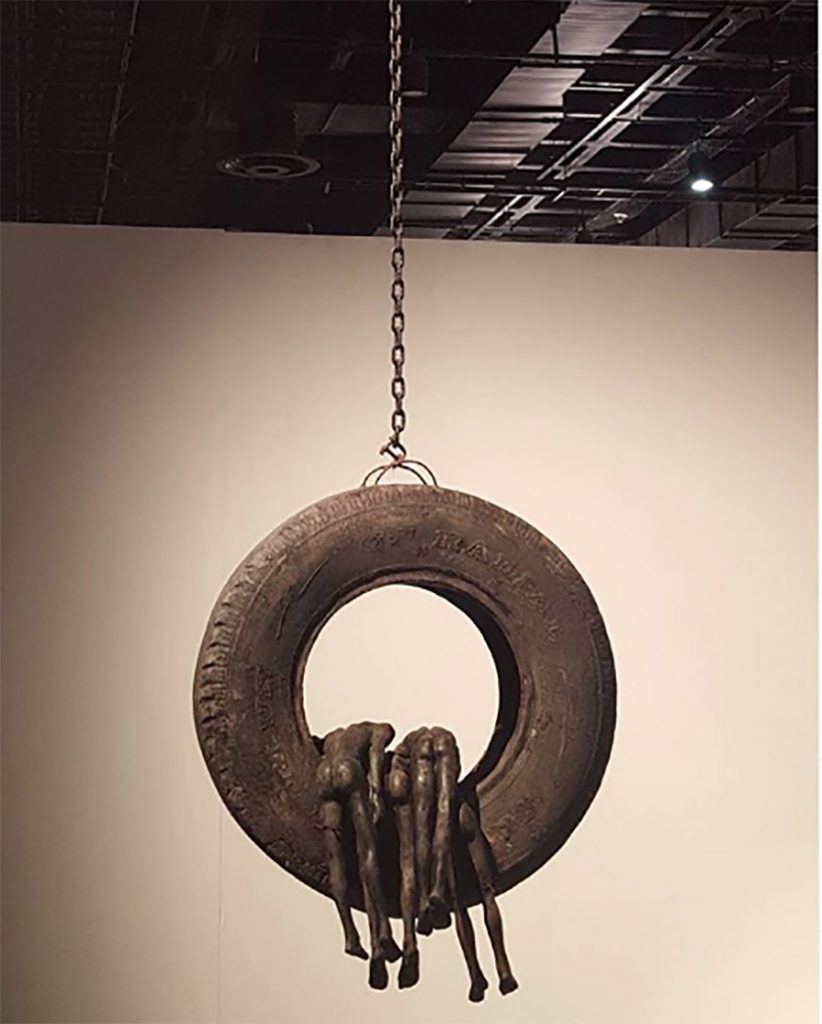

The Nigerian artist, Peju Alatise, addressed the issue of jungle justice in her work O is the new + (cross) which she presented at the 2017 FNB Art Joburg Fair, where she won the FNB Art Prize in the same year. On 5 October 2012, four students from the University of Port Harcourt – Ugonna Obuzor, Toku Lloyd, Chiadika Biringa, and Tekena Elkanah – were falsely accused of theft in Aluu, a community in the Ikwerre local government area in Rivers State, Nigeria. They were stripped naked, beaten, tortured, dragged through the streets, had concrete slabs dropped on their heads, and car tyres filled with petrol were wrapped around their necks. They were burnt to death. The footage was shared on the Internet, and it went viral leading to provocations and protests. On 31 July 2017, a police sergeant, and two other individuals were sentenced to death for their involvement in the unjust killing of the young men now known as the Aluu Four.

Watching videos of the Xenophobic attacks on the internet evoked sadness. How does one process the imagery of this black-on-black violence? Some victims were burnt alive. Like the Aluu Four, they were subject to ‘necklacing’ (when a tyre drenched in gasoline is put over the victim’s head and set on fire), a form of torture inflicted on people suspected to be spies during the apartheid regime. While xenophobic violence has been present in post-apartheid South African society, the attacks weren’t attributed to xenophobia but treated as part of the crime problem in the society. The international headlines generated from the May 2008 xenophobic attacks that killed about 62 people, and the 2015 attacks targeting Africans in the black townships of major cities of the country changed all of that.

Journalist, Nicklaus Bauer, in the Mail and Guardian (May 2013), cited four instances of major xenophobia-related incidents since 2008: The June 2009 meetings held by business people from four Cape Town’s impoverished communities discussing ways of ridding their communities of foreign-owned shops, the June 2010 claim that xenophobia may erupt in South Africa after the FIFA 2010 World Cup by a group of eminent global leaders called the ‘Elders’ as jobs become more scarce, the October 2011 call for foreigners to vacate Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) houses in the township within seven days by the Alexandra-based group, the ‘Alexandra Bonafides’, and the July 2012 displacement of more than 500 foreign nationals in xenophobic attacks at Botshabelo in the Free State.

The African Diaspora Forum (ADF), a pan-African NGO founded in 2008, has been working for social cohesion against xenophobic violence, and also working to integrate foreigners into South African society. The group talks about the contribution of the migrant population to the economy. It also believes that “the most exposed to xenophobic violence are the foreigners living in the slums and townships alongside black South Africans.”

On 12 September 2019, a batch of Nigerians fleeing the xenophobic attacks in South Africa arrived Nigeria. This was made possible by the laudable initiative of Air Peace, a privately-owned Nigerian airline. As the Flight B777 landed in Lagos, the crew, and the returnees displayed placards saying “No To Xenophobia”. Although they had lost everything, they were happy to be back home. The CEO of Air Peace, Allen Onyema, said, “Evacuation is not a good thing for any country. It sends a wrong signal to the International community about security and safety in a country.”

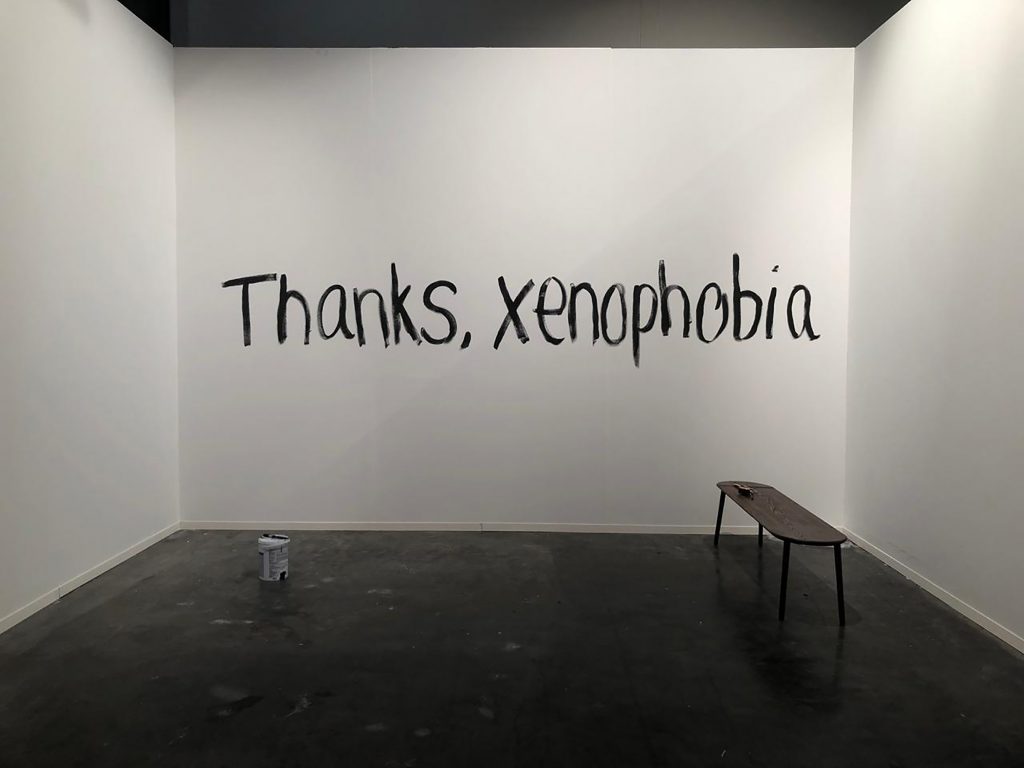

As the 2019 edition of FNB Art Joburg opened the next day at the Sandton Convention Centre, the Nigerian artist, Sheila Chukwulozie, had a graffiti message of her own in the empty booth of the Nigerian gallery 16/16. The words were “Thanks, Xenophobia.” The trio of Nigerian galleries, 16/16 & hFactor, Rele Gallery, and Revolving Art Incubator, were invited to the ‘Gallery Lab’ section of the fair.

While The Art Newspaper, claimed both 16/16, and Revolving Art Incubator (RAI) failed to obtain visa to enter South Africa after xenophobic attacks across Johannesburg, the statement on Revolving Art Incubator’s social media, precisely Instagram, is “In view of recent #Afrophobic attacks in #SouthAfrica, and the widespread reprisal attacks in #Nigeria, we withdrew our participation from the Gallery Lab of the FNB Art Joburg fair on Tuesday the 3rd of September 2019.”

Rele Gallery stated it obtained visa a day before the fair opened, and presented the works of Tonia Nneji, Sejiro Avoseh, and Marcellina Akpojotor. The Gallery manager, Kehinde Afolabi spoke to Artnet News saying “we made it here, and lots of South Africans have come to the booth and said they are happy to see us, and they keep apologizing for what is happening.” She further says, “Nobody wins in a war.” I think Jay-Z’s words are even more apt in this situation, “Nobody wins when the family feuds.”

Is a miracle needed to solve the problem of xenophobia on African soil? Where are the committed local and national leaders that will endorse and support anti-xenophobic campaigns in the country? Will laws be passed and implemented to safeguard the lives and properties of other African nationals?

Or maybe, what South Africa desires is a wall—a wall along its borders to avoid the influx of African ‘migrants’. If we are to live in a world that promises a united continent for all Africans, regardless of their religion, skin colour, orientation, cultural values, then we must work towards dismantling these invisible walls of hatred that have been built in the minds of the citizens who see their fellow Africans as their problems. Until that day, the vision 2063 of the African Union will be mere rhetoric, and a united Africa, even with a common passport, a balloon dream.

Great article