The Invincible Hands exhibition at the Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos, has the atmosphere of a gathering. A gathering of women from different periods of Nigeria’s history, daring to fill up the ostensible but often ignored gaps in the country’s historiography. The exhibition, featuring over 70 works from more than 40 Nigerian women artists, offers an avenue to consider the place of women in Nigerian art and history.

As one moves from vestibule to vestibule, one feels the dynamism of the show. In certain rooms, there is the quiet of a deep, private conversation; in others, there is the buzz of an excited gathering; in yet others, there is some intensity as befits a heartfelt address. Works like Nathalie Djakou Kassi’s Emerging Truth (2018), Antonia Nneji’s Through Mary Our Mother (2020), and Wura-Natasha Ogunji’s Conditions for Flight (2020) demonstrate the exhibition’s varied moods and concerns. Overall there is an air of agency that would not apologize or be dimmed.

These works move across time as across mood and theme, sampling a great range of material as though reaching to embrace the entire spectrum of women’s experience. Such an exhaustive embrace of life is apparent in Nike Davies-Okundaye’s Cycle of Life (1980), a large indigo-dyed tapestry hanging over a wide section of wall. The work offers a glimpse into the different aspects of the Yoruba worldview, depicting the cycle of life from birth to death and the intervening phases of work, maturity, and discovery. On the indigo are chalk markings in white, short diagonal lines, drawings of scissors, kernels, cowries, and ritual objects. The woven tapestry could be a rug in a house or a wall hanging, and Okundaye infuses it with potent symbolism, keeping ancestral wisdom and techniques alive and relevant to how we live and understand the world.

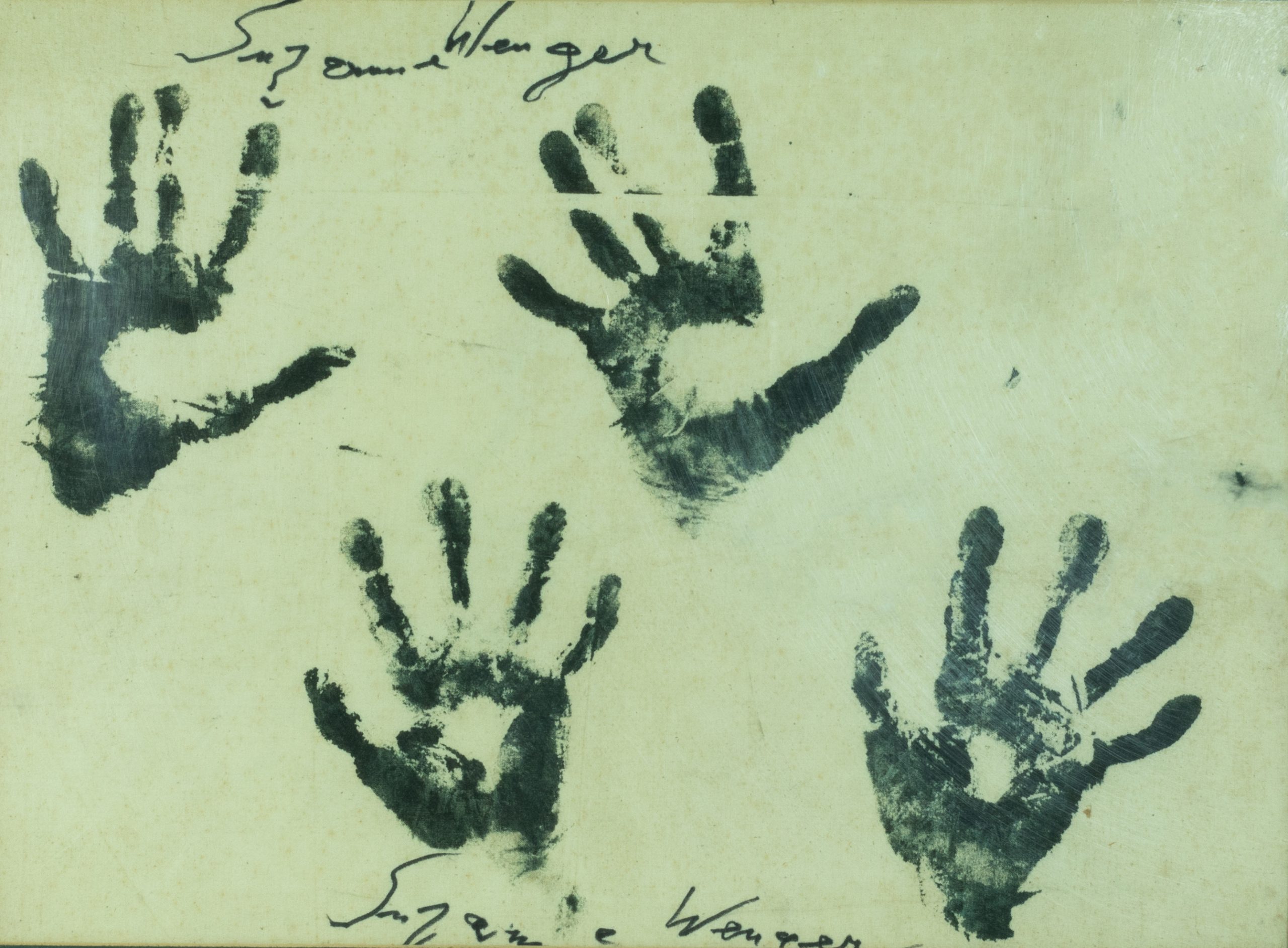

The deployment of symbols—of their varying meanings and relevance across time— lends an intense, almost viscous air to the vestibules. There are things not entirely understood, signs to be parsed, but these do not impede appreciation or even enjoyment; rather, they deepen curiosity. Several works are direct in subject and composition; their energy comes from a charge that hums through that plainness, like currents beneath a quiet stream. Susanne Wenger’s Palms of Destiny (1993), a painting of unpretentious, earthy minimalism, is not a quiet stream—it is four handprints on a matte surface. But in it, there is a simplicity, a clarity of expression charged by something alive, something haunting. The painting and its title may call to mind the saying: a person’s destiny is in their hands, an expression so common as to have been rendered cliché in modern usage. However, the overall effect of Wenger’s painting counteracts this trivialization. Through the painting, she impresses on one’s mind that considerations of destiny, often conceived as something inscribed on the palms, are no light matters at all.

Wura-Natasha Ogunji, Modupeola Fadugba, Nnenna Okore, Chigozie Obi, Chidinma Nnoli, Joy Labinjo, all stand close to each other in a passage of the museum, their works hanging next to each other on walls that enclose a central dais, much like dignitaries in a grand meeting. The conversation is effervescent. There are interrogations, comments and ripostes on society, history, women’s bodies, women’s agency, and women’s representation. As the curator Olufisayo Bakare says, Invincible Hands is intended “to weave a compelling narrative of inclusion.”

The point of the conversation is not to create a definitive list of women’s concerns. In fact, if there’s any discernible objective: it is to expand and complicate the space that art makes for women in the world, to weave a narrative of inclusion, not only to indict those who have profited from exclusion—for of course there certainly is that—but also to extend the conversation to include ways of thinking about women and about ourselves that we may not have considered.

ruby onyinyechi amanze’s Astroturf rooftop picnics (Lagos), Ghana must go (bags) somewhere, anywhere – overweight luggage unpacked at airport counters, isn’t a Chandelier like a plant? A delicate semblance of permanence, neon hearts, we all have them (2015) pursues its own fertile thinking. The canvas is large, and various ideas are playing out in different sections. Nothing resolves easily, and it is precisely for this reason that the painting is interesting. There is a central logic, an inquiry, an unfolding insight around which the elements and choices gather, towards which they point. To the right of the painting, a woman sits opening her chest and baring her heart, her legs stretched out in diverging directions. A little to the left of the woman is a Ghana-Must-Go bag. At the bottom left are figures who, in their helmets, resemble astronauts. At the top centre is a pigeon holding a chandelier from its bill. Besides the subjects, the canvas is a blank white field. The absence of patterns or designs leaves us trying to puzzle out the motif of connection. The lines that connect everything, the patterns that make it all make sense may not be immediately obvious, but the effort of finding them is worth it.

In fashioning such complex and richly textured conversations, women’s voices would become audible, resonant and far-reaching, reclaiming the spaces from which they had been erased. The artists in this show stretch across Nigeria’s geography and history like a bridge. They stand in solidarity with and hold the fort for women, Nigerian women who, among other things, led the Aba Women’s Riot of 1929, organized the Lagos Market Women Association of the 20s and 30s, founded the Egba Women’s Union of the mid-to-late 40s, all of which pushed back against colonial excesses and cultural disintegration; women who, with rare ingenuity, kept the country going during the Nigerian Civil War; women whose labours built the country.

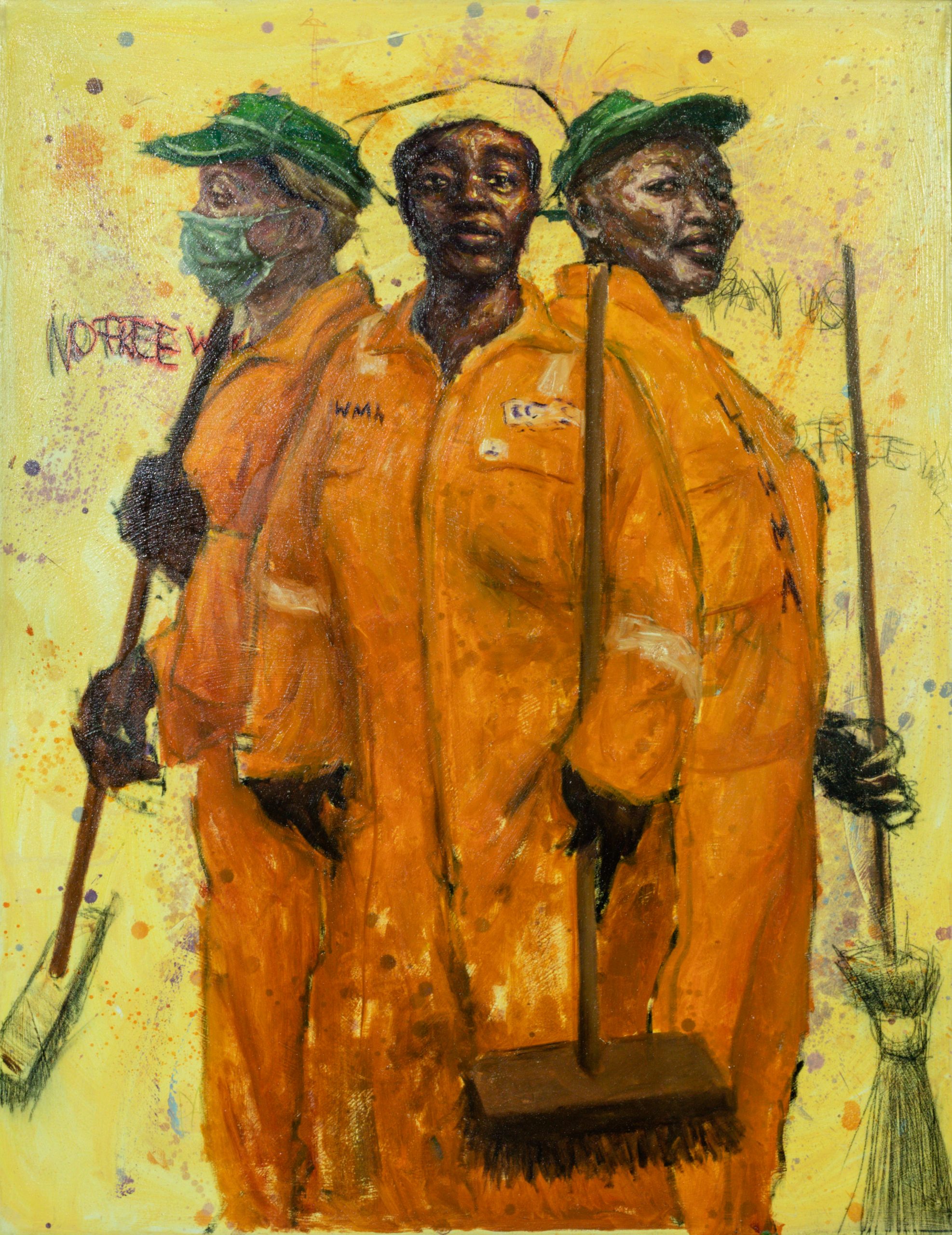

Against this backdrop, the case made for women in Chigozie Obi’s The LAWMA Workers (2020) stands out with remarkable eloquence. In the painting, three women stand, almost filling up the entire canvas, holding their brooms and brushes. The women in the centre and to the right have no masks on. Their posture is upright, their bearing and expression full of self-respect. Looking at them, one feels the quiet force of the phrase: the dignity of labour. But layered into the painting is a refusal by these women to be taken for granted or unrewarded for their labour. Words in bold, emphatic letters are etched onto the canvas: NO FREE WORK, PAY US. The third woman, though—she stands to the left, she wears a mask—looks dour. It is not hard to guess the reasons why the look in her eyes may be so bleak. She brings to the surface an entirely new set of queries: Are we truly valued? If we are, how much? What is the future for us? Her bleak gaze, expertly rendered, brings Obi’s painting full circle.

Another particularly arresting painting in the exhibition is Ngozi Omeje’s Light Up the Lamp (2019). A lamp built of small leaf-shaped terracotta pieces suspended from monofilament strings hangs from roof to ceiling as if in a vitrine. The strings catch the light, giving the effect of sunlight on a softly rippling stream. Omeje’s installation sparks diverse associations: a swirling of leaves, a clearing, a forest path, a shrine, a lamp, a house of light. A strongly religious aura surrounds the work, something earthy, elemental. The symbolism is not showy, but I suspect a thoughtful conspiring of several sculptural elements accounts, in part, for this effect: the size (awing), the medium (clay), the subject (a lamp), and the strings (their gentle play with the light). We are before a grove. We are walking through a forested path. We are to illuminate something before us, to dispel the dark around us. We are to let the light in.

Every work in the exhibition draws us into a steadily deepening experience, whether soulful—as is Chidinma Nnoli’s Girls Just Wanna Have Fun (Whine and Wine) (2020), in which eight elegant Black women find comfort in each other’s company—or serious—as is Peju Alatise’s 9-Year-Old Bride (2010), in which a young girl, a child (third from left) is forced into an early marriage, flanked by the adults taking her to her husband—or symbolic—as is Nengi Omuku’s Mama Rose (2019), in which a shawl draped around an absent body cradles a downy wreath.

The women in Invincible Hands are making spaces for themselves, erecting monuments. They are ensuring that their contributions to history and contemporary discourse are seen and heard. And while we may have been allowed in as audience, they make it clear that it is their show.

Invincible Hands is on view until January 25, 2022.

–

Joseph Omoh Ndukwu is a writer and editor living in Lagos, Nigeria.

Really avant-garde, in my OPINION. It’s a great read.

I liked what I read a lot.

This is a very intelligent article.