According to the World Bank in 1999, almost 491million people around the world had mobile phone subscriptions. In 2019 that figure was 6.7billion, increasing by 1265% in just twenty years. Internet usage similarly grew enormously from 2.07% of the global population in 1997 to 49% in 2017.

The 21st century has marked exponential growth in our virtual interactions. The consumption of information and entertainment on mobile phone and laptop screens have, in many cases, replaced that of its television predecessor and with it presenting new global interactions.

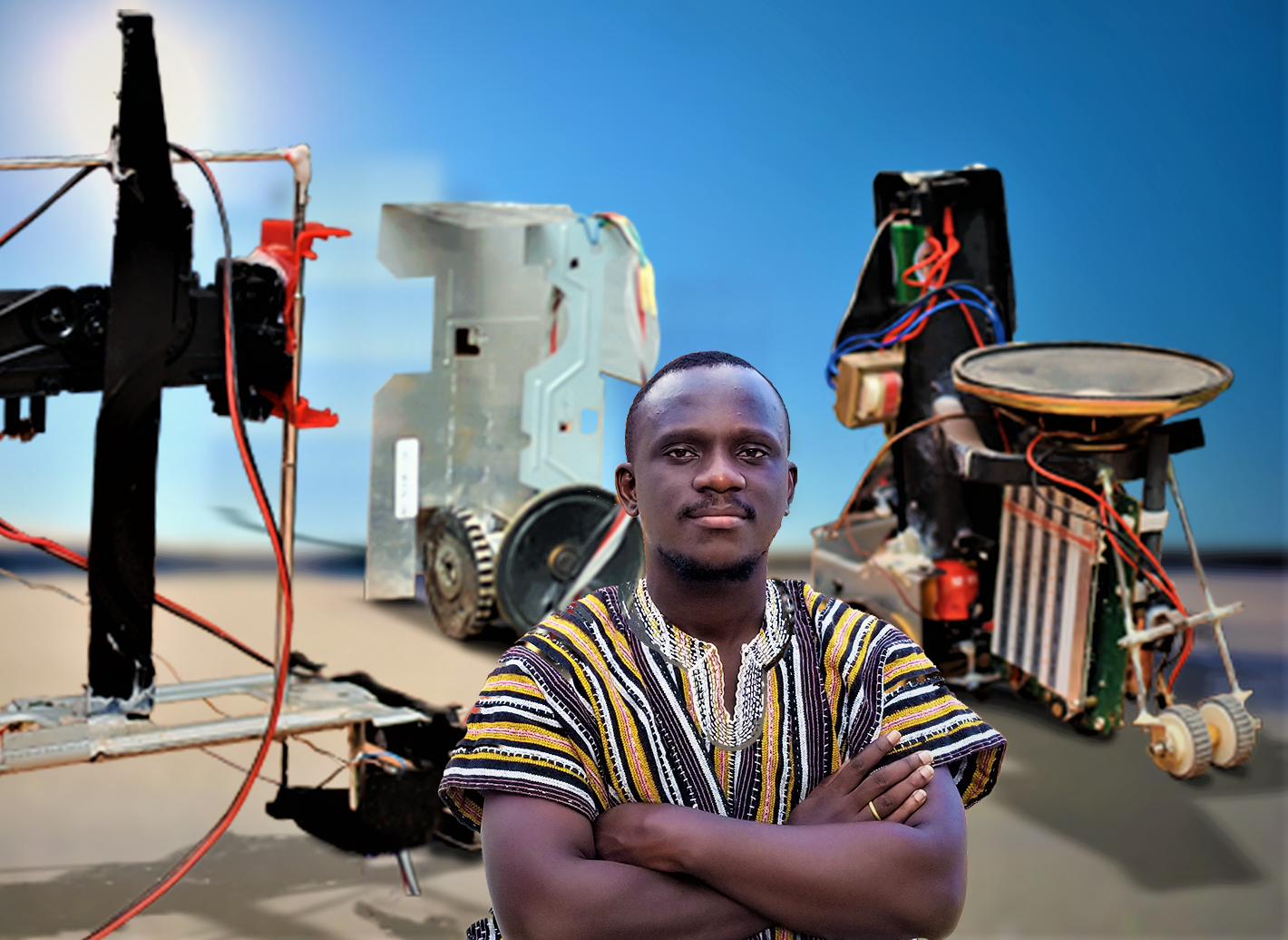

Ghanaian artist Akwasi Bediako Afrane’s work brings together immersive reality and electronics, encouraging multiple experiences when interacting with them. Interested in exploring human relationships with everyday gadgets, he notes that the electronics we use have become extensions of ourselves, with our hands rarely far away from these gadgets. “For me, the digital space is not separate from the physical space,” he says. “The digital or virtual space is an augmentation of our physical.”

Enter Akwasi Bediako Afrane’s world of TRONS.

Taking inspiration from Michael Bay’s ‘Transformers’ films, Afrane became interested in exploring the idea of electronic objects having a life. “You could see within a scene someone’s car steering wheel, a vending machine and an XBOX 360 console becoming Transformers after coming in contact with an energy wave from the AllSpark,” he recalls. “In order for me to exhibit these being-like characteristics, I had to become an AllSpark (a prosthesis) aiding the transformation of the [gadgets] inspired by these images I’d seen in the [films].”

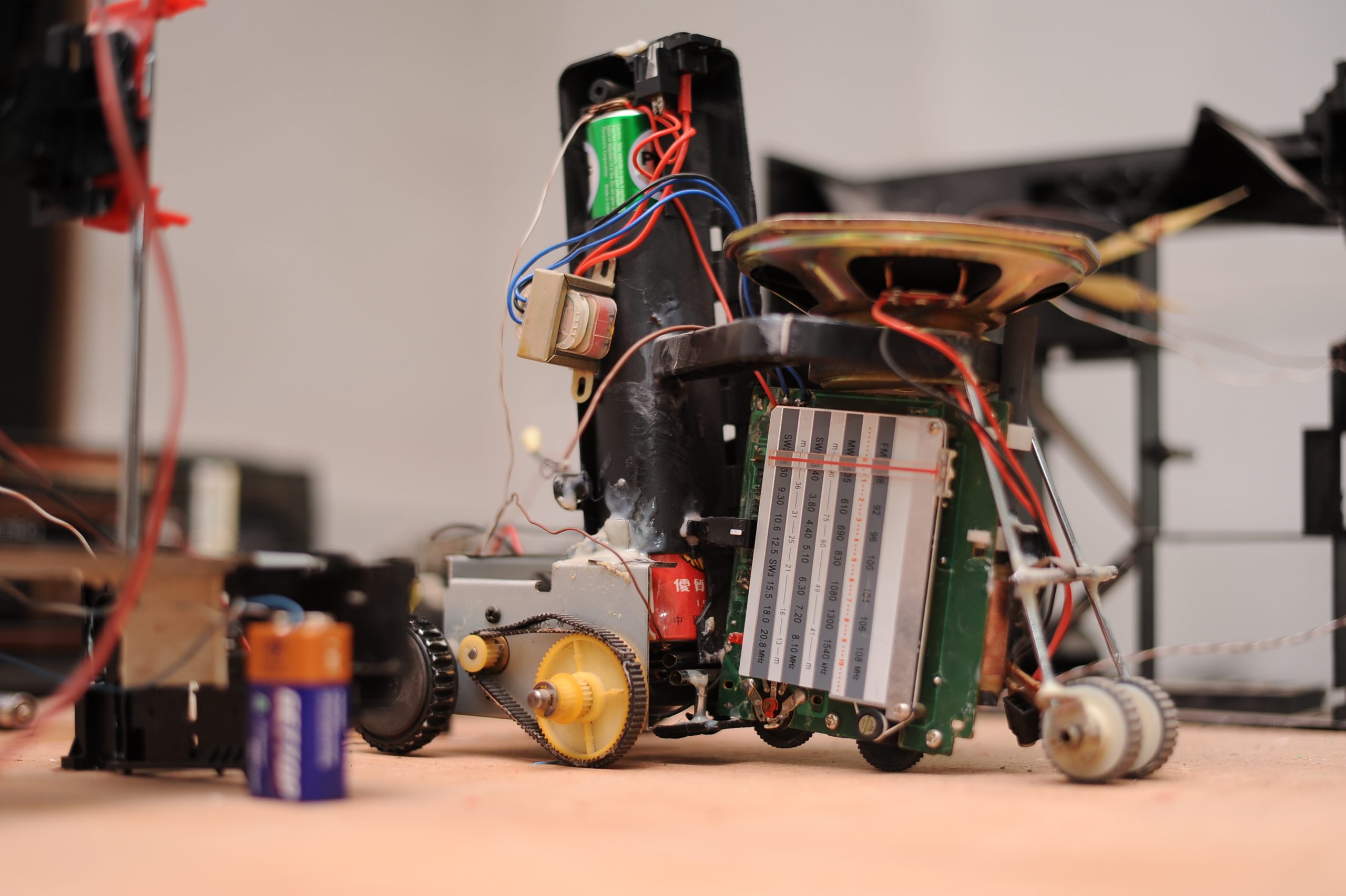

His making process is intricate. Afrane collects near-obsolete gadgets from friends and colleagues, gadgets they discarded in favour of something new and shinier. He removes their casings, down to the bare bones, and then starts the work of bringing light and movement to the gadgets. Thus, giving them life. To create his work, Afrane takes on the multiple roles of a collector of things, an upcycler, an electronics technician and a programmer.

“After these gadgets are stripped of their familiar casings, leaving only the printed circuit boards and other components, I transform them by adding or taking away from them. For components like the lights, sometimes, I upgrade them with newer LEDs.” Afrane uses Arduino, a microprocessor that helps with programming some of the gadgets. It aids in programming the LEDs to turn on and off or behave in a particular way. Likewise, he uses DC motors to bring movement to the objects.

And so, these gadgets are transformed from being our prostheses to embodying something like a living thing. The TRONS also hold another significance. In a world where new is often seen as best, Afrane particularly seeks out gadgets he describes as amputees, old electronics that have been let go. He refers to these gadgets as amputees as a way to consider their relationship with their previous owners, a severed relationship, which he says in a way renders them disabled. In a similar line of thought, Afrane sees the gadgets as a gateway for humans to enter the virtual space, a space that exists even if we don’t access it.

“I create these TRONS as a lens into critiquing our consumer culture within the capitalist system, so for me, it’s imperative that I use the discarded or obsolete ones,” Afrane reveals. “I believe these discarded gadgets have shared histories with their previous owners, and by converting them into the TRONS, I can play around with these shared histories as I match them against each other.”

Afrane’s artistic practice is further centred around creating works and exhibitions that encompass physical and virtual experiences where the two elements depend on each other, but can also be independent. Here he mentions the immersive realities of augmented reality, virtual reality and gaming platforms.

In thinking about exhibition formats, he observes that the art world – generally – is cautious when it comes to the work of digital artists. This could be, he ponders, due to concerns of ownership. “The institutions, galleries and museums, thrive on exclusivity and having power over a particular art piece that they collect,” he notes. So, with a digital work, which, by its nature could be open-sourced and readily accessible by whoever has a mobile phone, how would the galleries, museums and art centres be able to regulate who interacts with it (or owns the work).

There are, of course, across the world, institutions that are engaging the work of digital artists. But they remain mostly on the fringes of exhibition experiences. It is also important to note that for people to be able to engage a digital work from home, they may have to acquire some screen devices, for instance, a television, a mobile phone, a laptop/PC or a VR headset, which comes with cost hindrances.

WATCH: “Ghosts in Shells” by Akwasi Bediako Afrane. CLICK TO PLAY VIDEO.

Nevertheless, Afrane believes that the technological phase we find ourselves in, the Digital Age, “democratises art for the masses.” He points to an observation from French poet and essayist Paul Valéry who, in 1928, spoke of a time where artworks might be easily accessed at one’s fingertips. “Works of art will acquire a kind of ubiquity,” Valéry wrote in his essay The Conquest of Ubiquity. “We shall only have to summon them and there they will be, either in their living actuality or restored from the past. They will not merely exist in themselves but will exist wherever someone with a certain apparatus happens to be.”

Here, we might think of Walter Benjamin’s Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction — in which Benjamin opens with a quote from Valery’s essay—which in part considers the effect technology has on cultural and artistic production as a result of the way art is reproduced and consumed. Now, in the year 2020, Afrane suggests that the technologies available to us can continue to push these boundaries.

Consideration of the exhibition format is just as important for Afrane as the produced work. So he encourages the idea that artworks should be created with some of the available display technologies in mind, from the beginning.

“As artists, one of our major intentions is to connect with our audience… We are pushing forth ideologies,” Afrane argues. “I feel the art world is still concentrating on works shown in one form. Various technological means can be utilised to maximise audience experience.” Such exhibition forms or display formats include social media, which in the last few months, since the onset of the pandemic, has been a hub for interaction with art, artists, audiences and institutions. The art world, unwittingly, was forced to re-strategise.

Reflecting on the last few months, he adds: “With COVID a lot of us were not prepared because we believe that physicality is absolute. We were too focused on mano-a-mano interactions.”

Technology, Afrane says, is intrinsic to art. “Even the act of creating a brush, paint, a canvas, these are all technology-based. The act of using a sharpening stone or tool are technology-based.” So, for him, a transition to new virtual technologies should be a natural progression.

That the art world is reluctant to keep up with the pace of digital technology could be telling of the times. It is common these days to hear of people taking social media breaks, or going to retreats banning the use of digital electronics in an attempt to restore productivity into their routine. While many find these to be worthy and often necessary actions, Afrane views the language around these decisions and the reasons as vague and amusing. “If someone wants to go off this technology, it is fine. But if you want to be productive and part of this global village we’re living in, then going offline or off technology isn’t a good idea.”

In this “new normal”, as the post-COVID era is described, he wonders how grand exhibitions, like the Venice Biennale, for example, would incorporate the physical and the virtual for the audience to experience the show in its entirety. And by extension, he hopes that the documentation of such exhibitions, though useful in many cases, will become more expansive.

“In Artificial Hells, one of Claire Bishop’s critiques, was this idea of documentation,” he says. “If we were to miss an exhibition, our only choice of experience would be documentation. I am looking at possible ways through which an audience could experience an exhibition perpetually. Or a ‘takeaway’ experience, so when you leave, you can experience the exhibition in a different form.”

The year 2020 brought with it unprecedented actions in both physical and virtual spaces. And as physical spaces reopen, artists and practitioners like Afrane hope that the art world will not dismiss the virtual space.

“The future,” he propounds, “has the virtual/digital coded within it.”