In the first essay of our Resistance and Revolution series, Serubiri Moses reflects on the drawings of Dumile Feni and calligraphy aesthetic of Mohammed Khadda, against a backdrop of the Black Consciousness Movement and the Algerian Revolution.

1. Dumile Feni: Emotion, Line, Consciousness

I saw the reproduction of a lithograph, adjacent to writer and editor Stacy Hardy’s short fiction on the back page of a newsprint.[1] I was astonished by the boldness of the line, as well as the subject matter. The text alluded to Ruth First and Lillian Ngoyi, historic figures in South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement. This is my encounter with artist Dumile Feni in the Pan-African periodical Chimurenga Chronic.

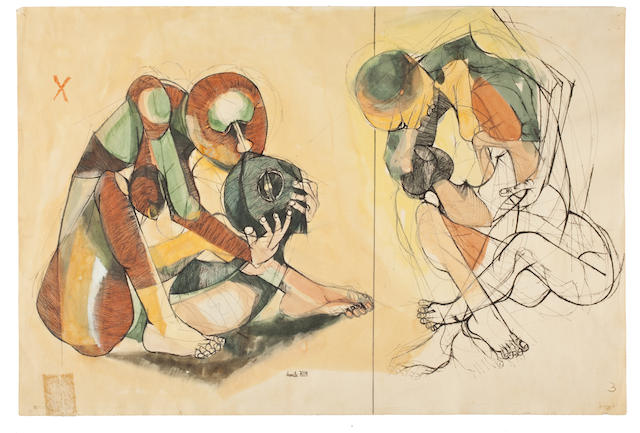

“In Dumile Feni’s fantasy,” Hardy wrote, before noting the seemingly intimate portrayal of two women, “It’s Ruth who moves first. Ruth first, pulling Lillian towards her. At first hesitant, lips meeting, just lips, puckered. A simple peck. A symbolic gesture of sisterly solidarity.” This statement reveals the stakes of Feni’s work as a push and pull between solidarity with African intellectual movements and engrossing sensuality. “But it doesn’t end there. In Feni’s fantasy the kiss is just the beginning.”

The lithograph in question reproduced in black and white on a full page of newsprint, depicts two women wearing army berets in an embrace —one of them wears a cloak that wraps around the other. I immediately thought the short fiction printed beneath it was a story of either love or camaraderie — or both in the revolutionary sense. As Joseph Beam wrote, ‘black men loving black men is the revolutionary action,’ but I didn’t invent the expression. Was Feni’s work about love or about revolution? Love as a revolutionary gesture shaped my encounter with the drawing.

Born 1942, Dumile Feni began his practice in sixties South Africa, with both solo and group art exhibitions, and internationally at the Sao Paulo Biennial in Brazil. In 1969, his eponymous departure into exile signalled the uniform departure of many Africans during the sixties decade and earlier. While I couldn’t locate a quote from Feni on his leaving, in contrast, the earlier move of artist Ernest Mancoba in 1938 is now perceived, albeit without complication, in light of his contribution to European modernism. In an interview with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Mancoba said, “The reason for my leaving South Africa was probably when I understood that I would not be able to become either a citizen or an artist in the land of my fathers.”[2] He questions participating in ‘empire’ exhibitions, a strong factor in his decision to leave. By contrast, apropos Brazil, Feni is accused of representing the ‘empire’ agenda of the Apartheid government.

In order to distinguish themselves from the aesthetics favoured by the ‘empire’ agenda and its equivalent in the academy, both artists would develop rigorous aesthetic tools addressing the question of state propaganda. Feni’s biographical notes suggest that he had no formal training, and that he came into contact with other artists while a patient at Charles Hurwitz South African National Tuberculosis Association (SANTA) Hospital in Johannesburg, recovering from a bout of tuberculosis. Ephraim Mojalefa Ngatane is credited as one of the artists with whom Feni created murals in the hospital. Yet it is a troubling detail in the artist’s biography because it denies his learning beyond these official institutions. Did Dumile Feni receive a cultural education? What was his making and unmaking?

The Black Consciousness movement in South Africa began in 1960 triggered by the Sharpeville Massacre. This along with a few other markers are agreed upon. Steve Bantu Biko’s 1978 book I Write What I Like is an account of Black Consciousness. Similarly, the Soweto Uprising of 1976 is another recognised event as part of the movement. With a central concern in language, the 1976 student uprising is linked to other continental movements formed by African intellectuals that share a clamouring for African languages. Curator Khwezi Gule confirmed that students in the uprising have been vindicated by history.

The awareness of state violence before the 1976 uprising is evident in African women’s activism in the country. Though not affiliated historically with Black Consciousness, the 1956 women’s protest against the carrying of internal passports is notable in this regard. Equally notable is Miriam Makeba who was a crucial voice to the liberation struggle in her native country, as well as across Africa and its diaspora.

Whether Feni’s art was aligned with Black Consciousness isn’t much disputed. Art historian Same Mdluli confirms this in her review of Chabani Manganyi’s book The Beauty of the Line: The Life and Times of Dumile Feni.[3] She complicates this alignment by noting that the artist once said, “art should transcend beyond political protest and strive to make life better.” Not all art produced in the postcolonial era can be described as postcolonial. Manganyi pushes past political or modernist narratives, as Mdluli notes:

“Evidently, as Manganyi observes, throughout his life Feni was well aware of art’s limitations but despite this he acknowledges that his work continues to ask difficult questions concerning what happens when art meets politics.”[4]

The book is not an artist biography in the traditional sense. As a trained clinical psychologist, Manganyi’s deepest insights come from Freudian techniques in free association that reveal an analytical frame with which to study the artist’s life. Mdluli writes that notably the book’s interviewees emphasise ‘The Scroll’, a fifty metres long drawing on paper, which artist Louis Maqtubela describes as an “in-between style.”

Feni might have situated this in-between style in the emotive aspects of his work. The artist said he “learned to control the emotion” revealing changes in his style after departing South Africa. Formal considerations of his artwork cite the artist sketch or the line as crucial to his aesthetic. If the “unfinished” was an intentional strategy, was this Feni’s answer to the question of Black aesthetics? Feni’s art delineates what is ‘possible’ within art. This strategy is equally evident in the political theory of Marxist scholar Walter Rodney. In the interest of economic history, Rodney questions how Europe ‘underdeveloped’ Africa. Both artist and political theorist position ‘Africa’ against what artist Ernest Mancoba called “the conditions made to my people.”

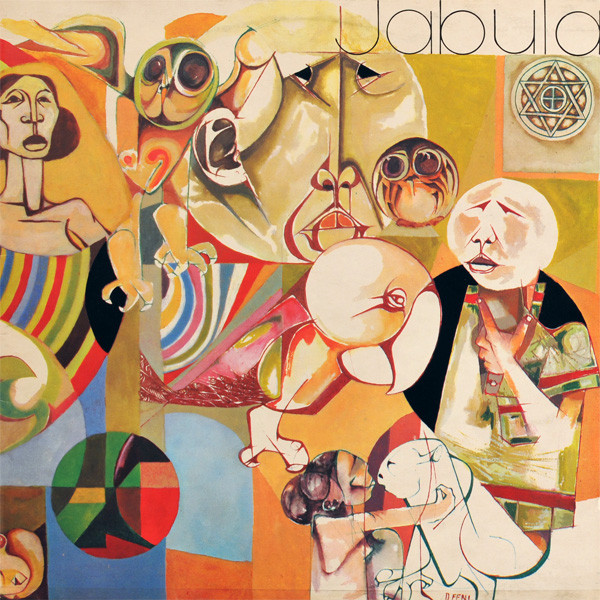

The figures in his art provoke lust, fantasy, or horror. Feni produces what Manganyi calls psychological portraits. Following the character of psychic life his subjects appear in dream-scapes. In London, Feni collaborated with musician Hugh Masekela and the ensemble Jabula, a collective of exiled South African musicians on such albums as Home is Where the Music Is (1972), Jabula (1975), and The African Connection (1979). In the album sleeves, his dream-scapes adopt the tight harmony of a vocal ensemble, or the somberness of a tenor vibrato. Masekela’s music births ecstasy found in furious dancing, or jolling in the night. That working-class African life is conjured through a combination of abstract portraiture, unfinished lines, and psychic life.

While the events that led to the consolidation of the Black Consciousness movement took place during Feni’s exile, he remained active, often contributing poster art to gatherings of transnational solidarity in the US and UK. Artists that share this experience of exile and Pan-African solidarity with Feni, are the sixty-member collective Medu Art Ensemble – a number of the members spent time in the late seventies and eighties in Botswana. Similarly shared is an emphasis on the lithography medium, that is evident in the artist’s practice, as well as in collective member Thami Myele’s lithographic print, The People Shall Defeat Aggression and Destabilization (1983).

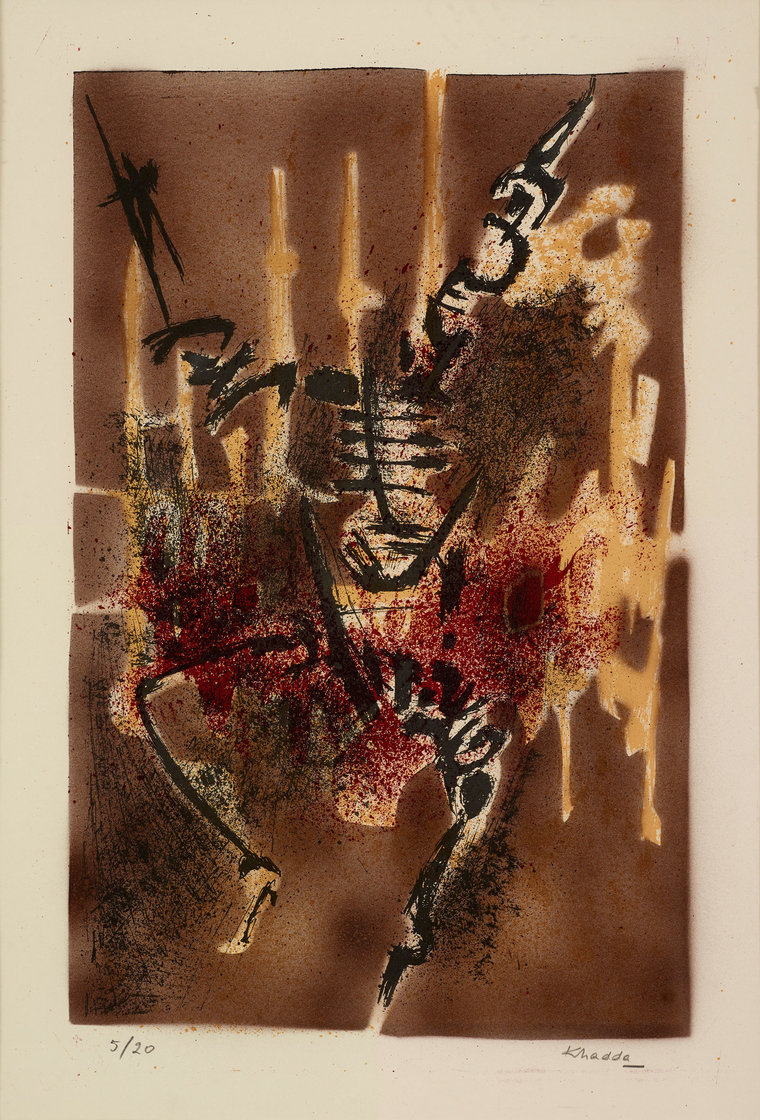

2. Mohammed Khadda: Double Consciousness and African writing

Abstraction Vert (1969) a painting by Algerian artist Mohammed Khadda provides an overall ‘plan’ or ‘system’. It is composite in its aesthetic mission. It allows for an engagement with spatial and geometrical thought. The canvas is a two-dimensional surface that positions various areas or spaces, echoing the geometric logic in an Arabic tradition. The illusion of three-dimensions with mutable overlapping patterns and the architectural methods of depth and field. In this latter sense, the work could be viewed not only as a plan but also as a ‘blueprint’ for the visual field. That is, providing a tangible aesthetic roadmap for Algerian artists during the sixties and beyond. The bright blue in the painting in one direct sense, distinguishes the calligraphic from these other logical elements. The painting, however, provides other sources of African logic. In the superimposition of surfaces, another plane is revealed.

The geometric layering of bright blue against bright orange against a deep velvet brown next to a rusty ferrous brown reveals the discursive character of the work through colour. I am drawn to the browns as an autonomous field or another plane. That is, while the calligraphy does stand out, this complimentary plane provides symbolic clues about the painter’s orientation to language. If the foreground presents a primary calligraphic mode, the background presents another calligraphic mode. It is this pivoting between colour and calligraphic modes that alerts me to an operation of double consciousness in the work.

Curator Suheyla Takesh reminds us that the work includes two languages, and writing systems, Arabic and Amazigh.[5] Arabic, being the primary language of communication in Algeria, alongside French; and Amazigh as one of the indigenous North African or Berber languages. An intentional awareness of the dual role of Arabic and Amazigh is at work in this visual space. This dual role suggests the artist’s aesthetic principles as being aligned to a project of decolonising Algeria from French occupation.

If an intentional double consciousness is present in Abstraction Vert then what does the double imply here? What meeting of spaces does it imply? It is a “double consciousness” seen equally in W. E. B. Du Bois. In an 1897 essay, he articulates the question of the double through a spatial logic set “Between me and the world.” Du Bois describes this sense of being ‘seen’ by the other in the racial encounter between blacks and whites in the United States:

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”[6] (ibid)

As a term double consciousness may equally capture the various issues at hand within the colonial encounter between France and Algeria. That encounter began in 1830. It is one in which a native is confronted with complex questions about space that produce a self-questioning; and in which the imposition of French consciousness becomes a problem.

I consider the emergent aesthetic as aligned with the ‘Arabic discursive textuality’ to paraphrase Iftikhar Dadi. And thus, a shared engagement with African writing in a discursive and calligraphic sense, connects Khadda with his contemporary Ibrahim El-Salahi. I call attention to their investment in the technical aspects of calligraphic writing in Sudan and Algeria, understanding its re-making as a roadmap for post-Independence art in both languages. African writing is expanded discursively to question the colonial encounter. A distinctly African consciousness in calligraphic writing calls to the imagination of a post-colonial space.

According to Aljazeera, the Algerian Revolution followed the century-long occupation, and manifested as an eight-year war with France. The central actors were the Front de libération nationale (FLN) and the French army. Like most liberation movements in Africa the FLN was preceded by an intellectual course, which bore directly on liberation by imparting its consciousness. The Algerian war occurred between 1954 and 1962, and was characterised by heavy military deployment, and torture of intellectuals and militants, such as Larbi Ben M’hidi. Arguably this consciousness took shape in periodicals such as Révolution africaine, to which Mohammed Khadda contributed, and El Moudjahid, to which Martiniquan psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon contributed. Takesh notes that Khadda’s theory of art manifested in the activities of the Peintres du Signe (sign painters), a collective of painters focused on calligraphic language and abstraction. Thus, revealing a practice aligned with the formation of post-Independence Algeria.

In reference to a broader historiography of Khadda’s contemporaries, French poet Jean Sénac published art criticism and organised art exhibitions devoted to Algerian art. Between 1964 and 1975, this critical work aimed at forming a definitive language in which to describe the developments that Khadda and his colleagues were making. The poet’s attention to colour and space is notable. Besides Khadda, among those mentioned as operating within the “Peintres du Signe” (to quote Sénac), are native Algerian artists some of whom include Abdallah Benanteur, Mohamed Aksouh and Baya (Fatma Haddad).

3. The Field

Artists Mohammed Khadda and Dumile Feni both set out to provide a plan for the visual field. This plan can be contextualised through the general historical timeline of the sixties across the continent. While indeed this period has been called “the short century” by Okwui Enwezor, it is important to view the artists as responding to a pluralism of discourses, rather than cede their work to a category of “postcolonial art.” Indeed, the sixties were a vibrant moment in which the Civil Rights Movement, and Black Arts Movement in the US, coincided with the Algerian war, the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, and the Black Consciousness Movement in the Republic of South Africa. It is the period in which artist Ibrahim El-Salahi and Mohammed Khadda carry out a significant process to revive cultural consciousness through their artistic realignment in African calligraphic writing. It is the period in which Dumile Feni encounters the activist Ruth First, and in which he begins to distil his psychic experiences through forceful, emotive and unfinished lines and only later “learn to control the emotion.” These experiences are multifaceted, as is their narration within ‘Africa’ in the Maghreb, the Caribbean, as well as Black diaspora.

“My subjects are Africans because they are my people,” Feni said. “But my message, the idea I am trying to put across has nothing to do with racialism —I am not interested in politics.” Thus, reaffirming his interest in African consciousness.

Similarly, Khadda “argued for a function of art beyond propaganda, or agitation.” His ‘plan’ which I have shown can be traced in Abstraction Vert is a roadmap of calligraphic abstraction.

I view both artists as individuals in dialogue with — but not entirely consumed by — broader anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements. I view them as affiliated with the Front de libération nationale and the African National Congress, but with considerate inclinations towards the role of art in everyday life. While they may design posters for solidarity or contribute to Révolution africaine, they also innovate new aesthetic philosophies. They are united in disagreement with the notion of art as mere propaganda. I imagine they would approve of novelist Dambudzo Marechera’s statement that “a developing country doesn’t need a writer like me.” Their idea of artistic expansion was not tied to civility, but rather to a combination of consciousness and aesthetic practices.

Serubiri Moses is an independent writer and curator based in New York. He is currently guest curator at MoMA PS1, and Adj. Asst. Professor in the Art and Art History Department at Hunter College.

[1] Stacy Hardy. Short Story in Chimurenga Chronic. July 2014.

[2] Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ernest Mancoba. “Ernest Mancoba: an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist.” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art. 18, no. 1 (2003): 14-21.

[3] Chabani Manganyi. The Beauty of the Line: The Life and Times of Dumile Feni. (KMM Review Publishers: South Africa, 2012).

[4] Same Mdluli. “The Beauty of the Line by Chabani Manganyi” review. Artslink.co.za. 07/24/2012.

[5] Suheyla Takesh. “Introduction” in Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World 1950s-1980s (Grey Art Gallery, New York University: New York, 2020)

[6] W. E. Burghardt Du Bois. “Strivings of the Negro People”. The Nation. August 1897.