For the fifth edition of Forecast, Koyo Kouoh, executive director and chief curator of the Zeitz MOCAA, mentors three young curators, Myriam Amroun, Aude Christel Mgba, and Ozoz Sokoh, and fosters a spirit of curating beyond the scope of traditional exhibition spaces.

The 2040s. Nigeria. A group of young farmers travels to Lagos. Along with a cultural producer, they tour some schools to plant in the young minds the seeds of a future away from urban centres. During their tour, they attend the preview of an exhibition that showcases local agricultural innovations. It features their re-introduction of old crops better suited to the frequent periods of drought the country is experiencing. Meanwhile, in Algiers in Algeria, members of a dynamic art collective attribute their collaborative approach to art-making to their childhood community art centre. It is a sentiment echoed by a young Cameroonian-born artist whose last performance memorialising a series of political uprisings re-ignited debates over civil rights.

These scenes are fictional, bordering on quixotic. However, they encapsulate fundamental questions about the boundaries of artistic practices. These speculative scenes also bear the imprints of the far-reaching social, political, and cultural changes that could derive from innovative curatorial practices such as those developed through the mentoring program by Forecast. Every year, in what could be described as a trans-generational passing of the baton of knowledge, the platform calls upon leading professionals in various fields to become mentors. Each mentor is tasked with guiding a shortlist of cultural producers and artists to develop their respective projects. This process culminates with the nominees presenting their developed work, and then a winner is selected in each discipline. The tiered selection process turns each project into a unique conduit of knowledge transfer. And every African nominee represents an additional opportunity for capacity building in the creative sector of the continent.

From the sixties onwards…curators conjured images of power and influence rather than ideas of mediation.

Koyo Kouoh, the chief curator of the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, was one of the fifth edition mentors. In her introductory video, Ms. Kouoh expounded on her creative approach, centred on building institutions enmeshed in their local communities and a curatorial practice that extends to fields “far bigger than what we have learned to consider the space of the exhibition.” Her choices of Myriam Amroun, Aude Christel Mgba, and Ozoz Sokoh align with her curatorial ethos, summed up in the title of her category: ‘Curating as Unearthing’.

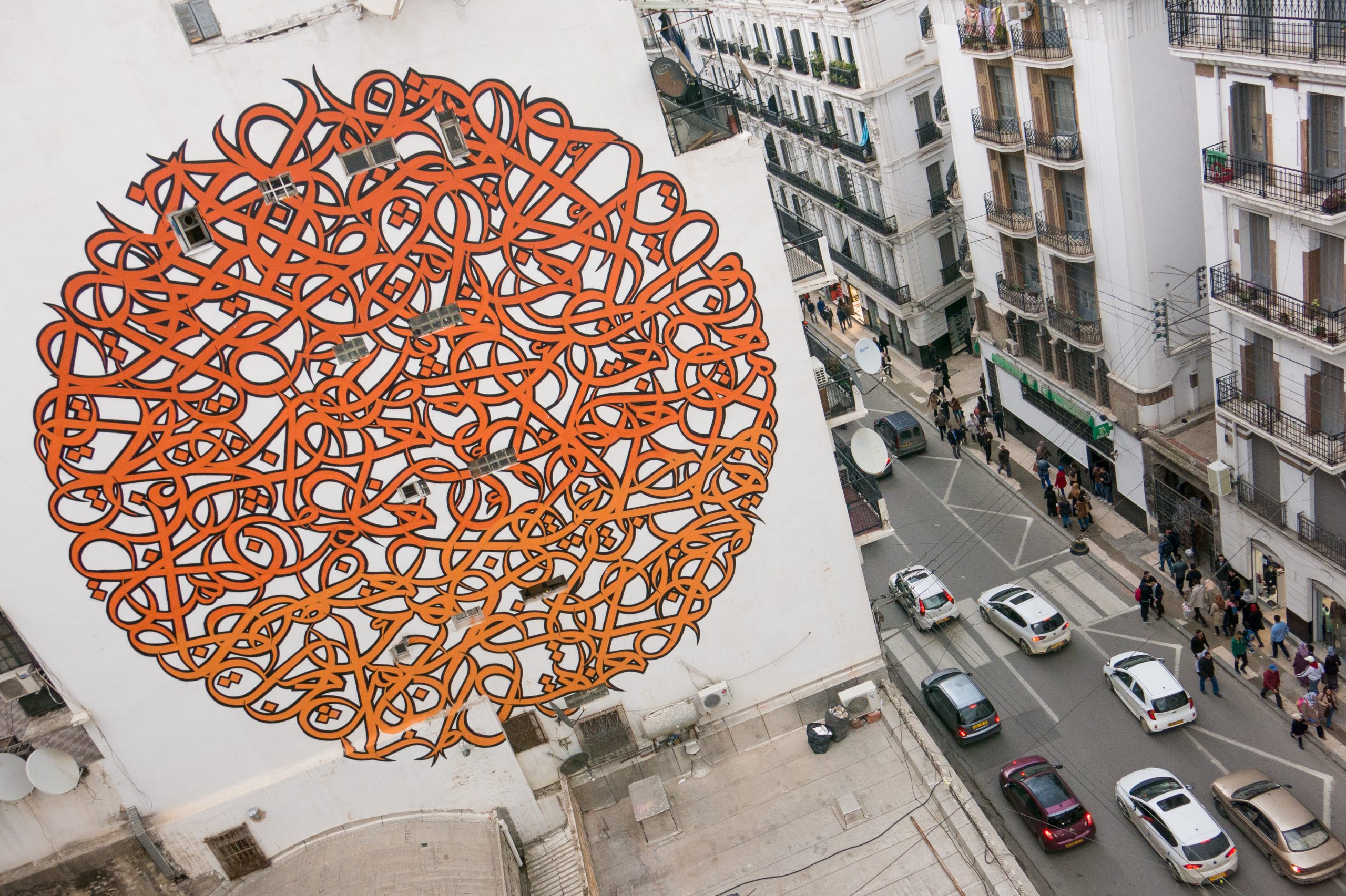

Amroun, filmed preparing for the opening of the rhizome’s first physical space in Algiers, five years after the organisation’s inception, gave a virtual tour of the premises being refurbished and highlighted their plans to integrate into the local community. The multipurpose art space reflects Amroun’s curatorial practice, underpinned by a collaborative approach and social experimentations. Far away, in Cameroon, a new organisation, ‘Current Name’, has sprung up. Its founder, Mgba, describes it as an “alternative knowledge laboratory.” Its inaugural program delves into Cameroon’s past and present and examines the conflict that besets its English-speaking part.

‘rhizome’ and ‘Current Name’ are two young institutions situated more than three thousand miles apart, operating in different geographical contexts. Despite their differences, they have a shared vision of deep social engagement and commitment to being more than traditional art spaces. Instead, they have opted to be experimental spaces that operate in symbiosis with their environments and beget novel ideas.

These curatorial practices and the very collaborative nature of these nascent institutions constitute a significant break from the traditional and insular model that prevailed, primarily in the West. From the sixties onwards, curators, like their most popular figurehead, Henry Geldzahler, conjured images of power and influence rather than ideas of mediation. In the pre-social media era, curators were perceived as gatekeepers of the art world, restricting the recognition of other modes of artistic expression, a sharp contrast with a curatorial practice Ms. Kouoh describes as “enabling, making possible.”

Things have changed since then. Successive generations of curators have enlarged the field of possibilities, especially for black artists. The rise of social media networks has rendered the curator’s title (whether it is self-assigned or not) ubiquitous in the multi-hyphenated biographies rife in the digital sphere and today’s art world. However, in all these iterations, the curatorial practice has remained fundamentally tethered to exhibition spaces, artworks, and related documentation.

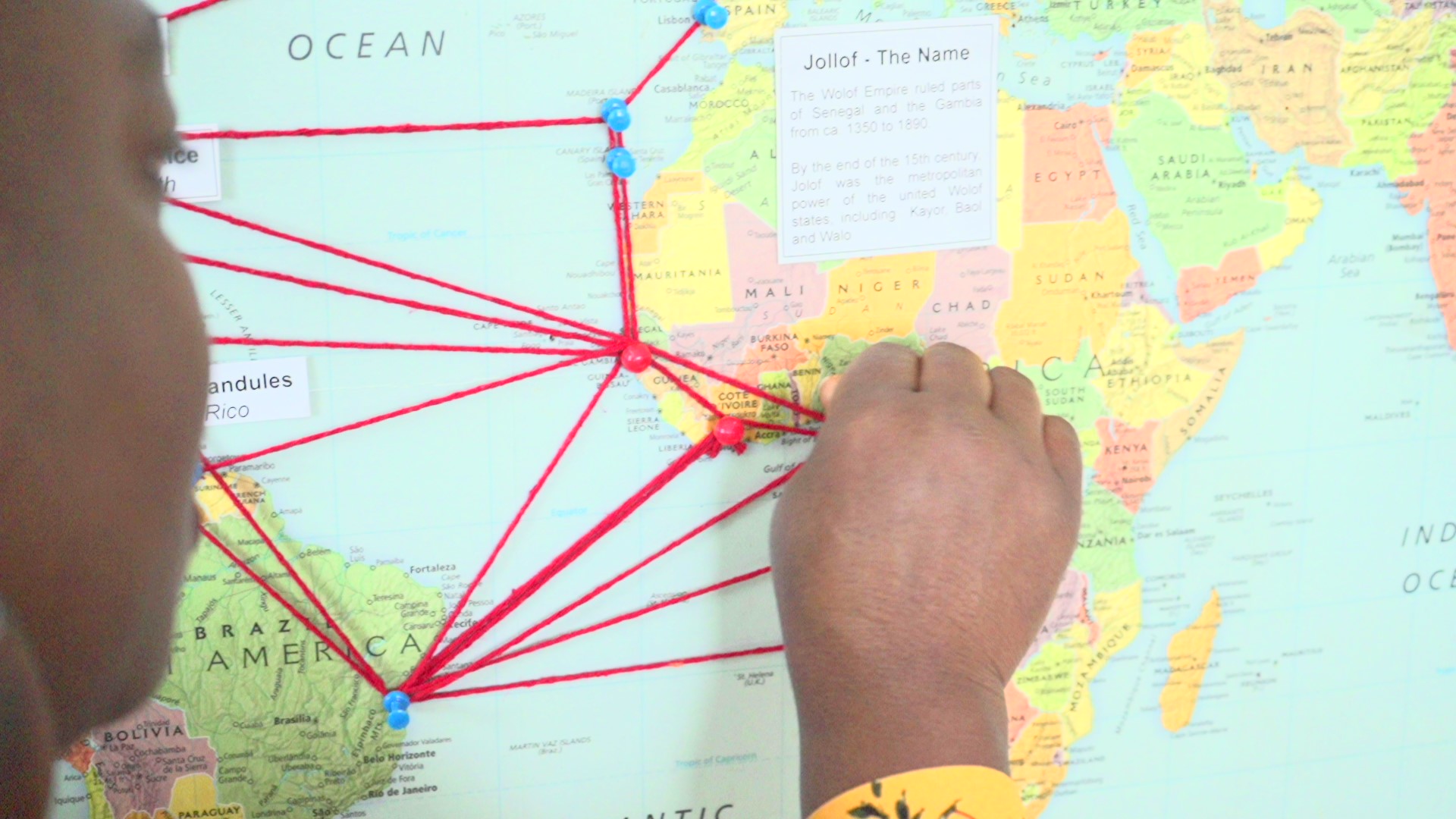

That’s the reason why the culinary-based artistic practice of Sokoh comes across as fresh and innovative. She was the ultimate winner in the curatorial category with her project’ Coast to Coast: From West Africa to the World’. In the project, she investigates through food the historical connections between West Africa and the Americas. “Food is the medium.” She explained in a Zoom call where she passionately proclaimed her love for food. “I love cooking. I love all aspects of food.” It’s a fondness that led her to coin the statement “Food is more than eating” in 2013. The catchphrase encapsulates her work and vision. Sokoh activates with food a time travel across continents to discover the history of dishes or ingredients and their varied usages. Taking a multi-disciplinary perspective, she queries visual culture, agricultural practices, historical and literary records.

The African American experience has roots somewhere. It’s anchored in their West African past, and that for me has been the missing part of the story.

This multi-disciplinary approach that she characterises as “generalist” came gradually. It was informed by her eclectic professional background and relentless learning on the go attitude. In 2009, Sokoh worked as a geologist in the Netherlands when a personal quest for identity and meaning led her to launch the food blog Kitchen Butterfly. She started using food to mediate her memories of her home country Nigeria. That thirst for connection further led to the discovery of culinary links between Nigeria and Brazil. Returning to Nigeria, she ramped up the research component of her practice, “documenting everything from ingredients to utensils, to dishes, to techniques.” The artistic layer – added in 2015 with a first exhibition – became the glair that bound all these different components of her practice.

She has built over a decade, a body of knowledge that deconstructs food politics, still dominated by asymmetrical relations of powers, stereotypes, and a language register filled with pejorative idioms such as “bastard” or “thick” used to characterise African foods. What surprised her the most is that “the words that are used to discriminate against West African foods today have been in use for 400 or 500 years […] The other big shock is that these things were written, written, written.” She repeated emphatically.

Paradoxically, some of the written records have allowed her to uncover the intellectual contributions of West African slaves to culinary and agricultural progress on the American continent and beyond. These are fundamental chapters of history that have been silenced for too long. “Western Africans were targeted because of their rice knowledge. […] People look at West Africa and associate them with physical labour in the transatlantic slave trade, and they want to keep them there, in that space of suffering and toil. But it was more than physical labour that enslaved people brought to plantations. They took knowledge, they took techniques, technology.”

If all the mentees were to spread their newly gained knowledge…there might be a groundswell of interest for collaborative, multi-disciplinary methodologies that could foreground radical and new perspectives for our world.

Under the tutelage of Ms. Kouoh, Sokoh has become particularly attuned to the nuances of marginalisation, especially when it comes to West Africa. She recently commissioned a study of 10,000 hits from various web sites that describe the world’s best foods. Unsurprisingly, some of the first African countries to be mentioned were Tunisia and Ethiopia. Within the marginalised world of black food, there is further invisibility based on region and country. “There is a layering. There is still a culinary colourism.” And when eventually there is a showcase of black food, its Western African roots are often glossed over or not acknowledged. “The African American experience has roots somewhere. It’s anchored in their West African past, and that for me has been the missing part of the story.” It would have been interesting to see whether the exhibition ‘African/American: Making the Nation’s Table’ at New York’s Museum of Food and Drink acknowledged that link. Sadly, the show has remained under wraps due to ongoing pandemic restrictions.

Sokoh has a long-simmering desire to impart her knowledge to her fellow Nigerians and West Africans. The community she points to as her primary audience. She is leveraging the mentorship with Ms. Kouoh to figure out the framework that will best support her work’s multiple layers. For now, the mentorship has enabled her to articulate her existing knowledge better and conceptualise certain notions she didn’t know how to formalise. Their interactions brought further clarity, and more importantly exposed her “to a variety of approaches and people working with food as a form of artistic expression.” It has, she says, “really changed the direction of my work.”

If all the mentees were to spread their newly gained knowledge, and there is no reason to believe they wouldn’t. There might be a groundswell of interest for collaborative, multi-disciplinary methodologies that could foreground radical and new perspectives for our world. Only then would these imagined scenes of the 2040s in Lagos, Algiers and Douala feel less utopian.