Kovie Parker reviews the 2019 Lagos Biennial, “How to Build a Lagoon With Just a Bottle of Wine”.

The second edition of the Lagos Biennial opened to the public on Saturday, October 26, 2019, at the Independence House, Lagos. Occupying three floors of the 25-storey office building, the biennial stays consistent with making use of historic spaces in the city – as the maiden edition held at the old Nigerian Railway Corporation grounds. The Independence House which was commissioned by the British in 1960 as a testimonial to Nigeria’s independence, is a significant part of Lagos’ – and by extension Nigeria’s – history, and is a brilliant location for an exhibition which bids a provocation for artists and the public to meditate on the history and present makeup of a city’s built environment.

This year’s edition, with the theme, “How to Build a Lagoon with Just a Bottle of Wine”, presents works from over 40 artists and collectives, across various mediums. Co-curated by Antawan Byrd, Oyindamola Fakeye, and Tosin Oshinowo, all of whom have strong ties to the Lagos arts and culture scene. Most of the works presented seek to address the history and urban character of Lagos from the perspective of artists who either live in the city or have spent some time here. While other projects focus on urban concerns in different parts of the world, with the main aim of opening up conversations and reflections on environments – how they are built and inhabited, as well as the ecological, historical, and socio-political dimensions of the spaces we construct and inhabit.

Perhaps the most prominent installation on the first floor of the exhibition, Angolan duo Raul Jorge Gourgel and Sandra Poulson’s garment project “Plastic Broken Chairs, Juxtaposed” looks closely at urban spaces as sites for creative responses to the absence of adequate living conditions supplied by the government and respective institutions. The installation features 8 nearly identical red dresses hung from the ceiling by strings, and with transparent rectangular screens covering the upper part of each dress. Also part of the project are photographs and a video installation featuring subjects clad in similar red dresses, touching on the relationship between different modes of informality – economies, building techniques, re-appropriation of land by merchants, and the exchange of informal currencies.

As anyone who has ever lived in or visited Lagos can attest, the Third Mainland Bridge – once the longest bridge in Africa – is one of the most heavily trafficked vehicular links in a city notorious for hours-long gridlock traffic. The longest of three bridges connecting Lagos Island and the Mainland and as such an essential part of daily commuting in Lagos, the Third Mainland Bridge has to endure many forms of erosion and decay. Seun Keshiro’s drawings, “Utopian Proposals for the Third”, model imaginative and utopian proposals for relieving the bridge’s traffic during rush hour.

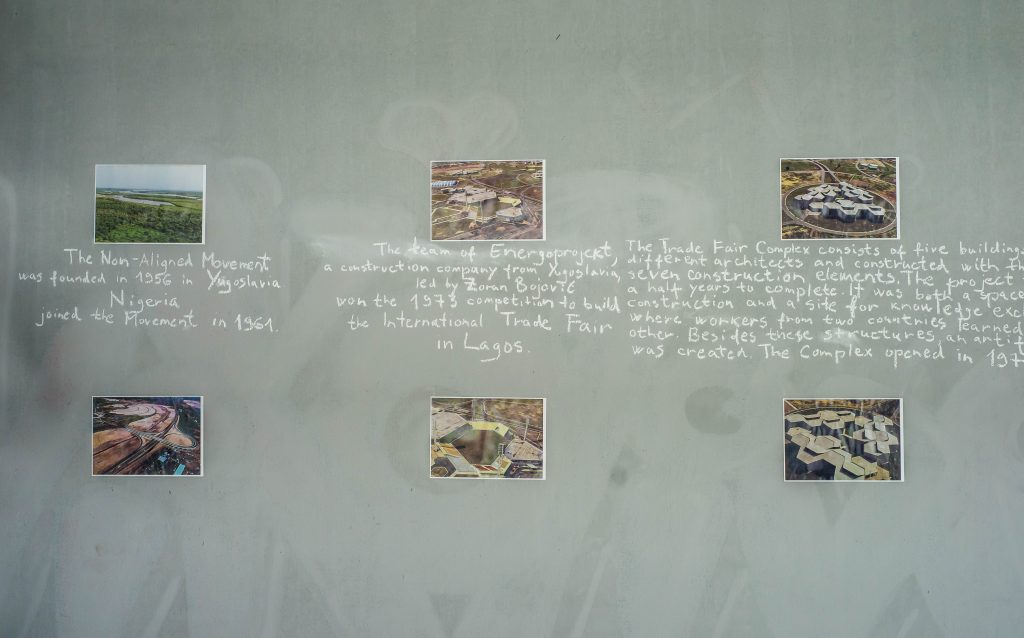

Several other engaging installations highlight facets of inhabiting cities, and specifically, Lagos. Rahima Gambo’s “A Walk Sculpture, Lagos” featuring a copper piping and found objects installation, iterate a body moving through a landscape (in this case, Lagos), and the entanglements that occur during this movement. Dane Komjlen’s “The Seven Elements”, is an installation of a reproduction of 14 archival photographs, and a chalk drawing which are all aerial representations of the Trade Fair Complex in Lagos, built in 1977. Over the years, the complex has been modified and repurposed into a large market complex, thus, the site’s initial history has all but faded from our collective consciousness. This progression, which the viewer is invited to participate in by walking in the chalk drawing and witnessing the Complex’s gradual obsolescence, highlights the evolution of lived spaces – the gradual transformation and modification based on need. Richard Zeiss’ “EKO Echo” measures and visualises variances in housing costs in Lagos, while Tom Bogaert’s site-specific installation, “Ant Farm Lagos” which consists of ants in a multi-coloured map of Lagos Island made of translucent agar-agar, symbolises what it means to be able to bend space, to live with the agility to move between particular social, religious, political, and economic registers.

There are a number of video installations strategically positioned across the exhibition site, including Karl Ohiri’s “Rolling Footage”, a short 4-minute video that explores what daily commuting is like for many of the physically impaired people of Lagos. The film, which focuses on a subject who suffers from lower limb loss and whose primary method of transportation is a self-built skateboard, provides a visual perspective of that Lagos that is rarely seen – one that brings the viewer literally closer to the subject’s world; providing insight into his daily struggles and triumphs, prompting a dialogue as well as questions on city planning, social welfare, and individual empowerment. Adeyemi Michael’s installation “Entitled” which comprises of a 4-minute film as well as an installation of 32 head ties and a pair of shoes, brings to the exhibition an issue that has been at the forefront of global discourse: immigration.

Perhaps one of the most thought-provoking works at the exhibition is Ndidi Dike’s site-specific installation “A History of a City in a Box”. A collection of hundreds of old wooden file boxes, some empty, others containing documents that are then concealed with sand. In the accompanying text, it is explained that this installation is inspired by Dike’s visit to Independence House earlier in the year where she discovered remnants of an office space that still contained bureaucratic government documents from the 1980s. In Dike’s own words, “Information is hidden and buried; it is inaccessible to the people, and only permitted to those in power”. By concealing archival documents and images of the city within the boxes, Dike models how urban political systems depend on the suppression of information to maintain order.

The thought-out and remarkably curated journey culminates in a sectioned corner of a room tagged “Wasteland”, where waste from the attendees are collected. Viewers are encouraged to dispose of their waste – everything from plastic bottles, to paper, snack wrappers, and more – in this open space. It will be interesting to see this collection at the end of the 5-week exhibition period. Perchance, keeping in line with the theme that focuses on the environment, this collected waste will shed light on just how much of it we produce, waste that would otherwise not be properly disposed for the most part – judging by the current state of the building where the whole affair takes place.

The Lagos Biennial runs till November 30, 2019 at the Independence House, and several other selected venues as part of its Off-ish programme showing the works of vibrant artists making provocative work in alternative art spaces in Lagos.