Khanyisile Mbongwa is a multi-disciplinary intellectual from Cape Town, South Africa. Her artistic and curatorial practices gained attention in the mid-2000s when she was part of the famous artist collective known as Gugulective.

In 2018, Mbongwa completed a master’s degree in Interdisciplinary Arts, Public Art and Public Sphere at the Institute for Creative Arts, University of Cape Town (UCT). In 2019, she was appointed the chief curator and artistic director of the first Stellenbosch Triennale currently showing in public spaces in the famous wine lands of Stellenbosch in South Africa. Prior, she was the adjunct curator for performative practices at Norval Foundation, based in Cape Town.

At her home in post-industrial Brooklyn, a suburb of Cape Town, I engaged her in a conversation about her background, previous curatorial endeavours, her approach to curating and the inaugural Triennale themed Tomorrow there will be more of us.

How did you get into the arts?

My background in the arts started at a very young age. I grew up in the township of Gugulethu, and I have lived in most townships here in Cape Town. In the early 1990s, we were socialised into the arts. My first tangible recollection though was the writing connection I had with my grandmother. Because I went to schools in the city, my grandmother bought me a journal and asked me to write about what I see when I travel from the township into the city. She asked me to describe the things that I see when I took the train, the bus, the taxi and then she would ask me to describe what I would imagine.

And what about your educational background?

I studied Sociology at Stellenbosch University, and I chose Stellenbosch, particularly because of my interest in race and racial dynamics Post-1994 in South Africa. Stellenbosch University has inextricable ties to the formation of Apartheid ideology, where some of Apartheid theorists and thinkers came from the university. It was important to go back to the cradle of one of the most violent human injustices and critically engage with the racial dynamics of today. After Stellenbosch, I went on to complete an honours program in curating at the University of Cape Town. Following this, I completed my master’s degree in interdisciplinary studies at the Institute for Creative Arts (ICA) under the aegis of Dr Jay Pather and Nomusa Makhubu.

When did you become a member of the artist collective Gugulective, and how did this shape your career and interests?

I am one of the founding members of Gugulective, which began in 2006. At the time, I was known as a poet. As I got more fascinated with the body as a site of evidence, I became more interested in translating my poetry and speaking through the body. That was how I got into the performative space. The Gugulective family functioned as a space for critical engagement, intellectual stimulation and rigorous political interaction. We didn’t call ourselves curators, but we were curating our stuff. So, my curatorial activities started here. We’d conceptualise and organise, and this influenced how I formulated my practice. My practice as a curator fundamentally is based on working collectively and basing it on collaborative processes. There’s a thin veil between curator and artist; I see our work in conversation and dialogue with each other.

Therefore, I thought to myself that we are going to have to open up the wound and the ‘woundedness’, not just of Stellenbosch but of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa and Africa as a whole.

What ideologies define your curatorial practice?

My curatorial practice fundamentally is based on two principles: Cure and Care. Cure, in the sense that, there is a ‘woundedness’ that we are dealing with and to celebrate our joy, our love, our beauty we need to cure the spaces that are full of illness. The core of my work is activating spaces for healing to happen and inviting artists to see that through their work, curing happens. In terms of care, we need to repair our institutions and care for the artists and their practices. We seriously need to think about how we do that curatorially. I learnt this because I worked so much with performance artists. I see how the world still doesn’t understand how to care for an artist when they are not painters or artists in the traditional sense. Care has become a crucial element in my practice, and emerging curators need to realise that it is something that you learn as you develop in your practice.

Before we get on to discussing the Triennale, can you share your experience curating the project Twenty Journey and the challenges of such a brazen endeavour?

Twenty Journey was my first massive project as an independent curator, and we needed a million Rand to make it happen. The concept of the project was to take a critical look at South Africa twenty years after apartheid and each photographer had a different departure point: Land, Born Free and Idiosyncrasies. There were many layers to the project, but four were fundamental: funding, travelling across South Africa for seven months, documentation of the journey via all social media platforms and the exhibition.

We organised a Kickstarter campaign to raise money. I applied to different funding institutions. We knew that we needed to get people to endorse the project — people who have the stature and social status. I put together a portfolio of all three artists’ works and approached a gallery. We built a website which was also a curatorial project as it presented their movement across the country. Interest in the project picked up at some point, and people offered their homes in the different places that we went and accommodated the artists for free. I hope to present the thirty years journey with women only. In the current climate of gender-based violence, what would it mean for three women photographers to travel across South Africa to look at our thirty years into democracy and what subjects would they choose to explore?

So, the Stellenbosch Triennale, what is the backstory of your appointment as the chief curator and artistic director?

I’ve worked with Elana Brundyn who is the director at Norval Foundation and also part of the board of Stellenbosch Outdoor Sculpture Trust (SOST), organisers of the Triennale. I have also worked with Dr Mike Tigere Mavura, another board member of SOST. I worked with him on different projects. They were looking for a chief curator and artistic director, and I suppose they wanted someone young and on the rise or making their way. Also, they wanted someone who had knowledge and understanding of the geographical location. We started having a conversation when they were still thinking about it in 2018. From the conversations we had, they made an offer. I have never done anything like this. Of course, there was Puncture Points and Twenty Journey, but they were different. I thought about them as one-off projects. Working on Stellenbosch Triennale required more long-term thinking.

Initially, it was conceived as a biennale, but later, we thought a triennale would give us three years to raise funds, conceptualise and to do research. I am very interested in building something that has longevity and continuity, and I was nervous because I knew that I was taking a career risk. It’s like an 8 Mile situation – there’s only one mic, and everyone is paying attention. My team, as well as every curatorial decision that we make, becomes important. I am lucky that I have a dedicated team and board of directors that are very supportive. Mid-way planning the production of the Triennale, I became pregnant, and it feels like I am birthing two babies at the same time.

What informed the curatorial methodology and the agenda for this edition?

When I accepted the role of chief curator and artistic director, I had to ask myself again: what is this place, what is this geographical location, what does it smell like, what does it look like? I knew Stellenbosch quite well because I lived there for four years. Also, in the process of this inquiry, I was initiated as an indigenous healer, which opened me up to ancestral time in new ways. Some of the issues that intrigued me are the misconceptions that South Africa is not seen as part of Africa, that Cape Town is not considered as part of South Africa, and that even Stellenbosch is not seen as part of the Western Cape. So, I asked myself: where are we?

It was important to find a foundation. I imagined people from the different parts of Africa coming down to the southernmost tip of the continent. That was my first vision, and the realisation of this amazed me. Then, taking into consideration the geographical location as an accused site of enquiry, its complex racial histories and where/how it positions itself now. Therefore, I thought to myself that we are going to have to open up the wound and the ‘woundedness’, not just of Stellenbosch but of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa and Africa as a whole. I tried listening to what the land wants to say and basing the identity of Stellenbosch Triennale on the idea of Sankofa, which is “to move forward you have to look backwards”. Again, it was crucial to bring forward the idea of the intersectionality of time and space and how Africans perceive the past, the present and the future as always being in dialogue.

At the precipice of decolonisation, what does cultural recovery look like? What are the emancipatory practices that are emerging? The phrase Tomorrow there will be more of us came to me as a series of questions about our interconnected existence with land and all life.

And how did you arrive at the theme Tomorrow there will be more of us?

I was in Germany at CAT (Community Art Team) for curatorial research and an exhibition titled Blueprint: Where There’s Nowhere To Go, Where Is Home? a project that engaged with historical legacies and future possibilities of public space, drawing intersecting lines across continents as a study of human flow as a historical and contemporary happening in how public space is imagined and created. While working on my research, I decided to visit the Biennial in Berlin curated by Gabi Ncqobo that was called We Don’t Need Another Hero. I sat there, and I was like “yeah, we don’t!”. Also, during that curatorial research, I imagined the earth crying and thought about how as black and brown people, we have been dispossessed of land and culture for centuries.

I wondered about this displacement on ancestral, spiritual and environmental levels. I wondered about what our futures would look like and how we could shape them given the current socio-political and socio-economic conditions continentally and globally. At the precipice of decolonisation, what does cultural recovery look like? What are the emancipatory practices that are emerging? The phrase Tomorrow there will be more of us came to me as a series of questions about our interconnected existence with land and all life. There is an urgent need for us to rethink our concept of space, resources and the distribution thereof.

What are the key exhibitions to see at the Triennale?

We have The Curators Exhibition, which is an amalgamation of some of the prominent and upcoming artists. This particular exhibition is about the present and how it is manifesting. In the practices of the artists who are part of this exhibition, there is a ‘present-ness’. There are only twenty artists, and some of them are popular names in the African art scene. However, I think some names are not as well known. The names to look out for, amongst others, are Helen Nabukenya, Kaloki Nyamai, Tracy Thompson, Reshma Chhiba and Ronald Machututa.

On the Cusp is another exhibition. It is about presenting artists who are young in their practice, on the verge of birthing something magical aesthetically or conceptually, and all they need is a final push for them to soar. Their exhibition is composed of ten young artists and an artist collective from across the continent. You have to check out all the artists here!

Then there is From the Vault which is looking at museum vaults. What’s in the basement of the museum? It is what we never get to see and how museums have acquired work overtime. For example, what and who did they choose to buy and what was the socio-political framework at the time? The works contained in this exhibition are primarily from the University of Fort Hare and Stellenbosch University.

The exhibitions are in common spaces accessible to the public, and this is emphasised as one of the goals of the Triennale. What significances or histories are associated with some of these locations?

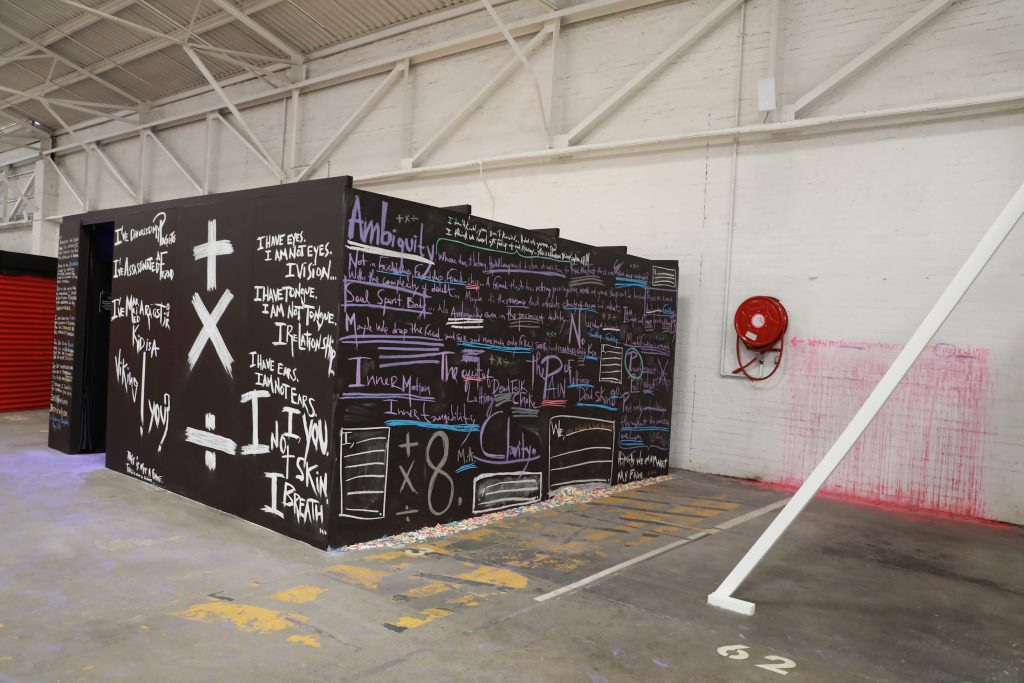

All the spaces are quite important. The Wood Mill, where The Curators Exhibition is showing, is historically significant as a place built on cheap black labour. It existence resulted in the birth of Kayamandi, a township on the outskirts of Stellenbosch Central Business District. Another significant location is Die Braak. Die Braak stands for fellow. It is an open piece of land. Approaching it, I asked that it tell me where it hurts…tell me where it hurts, and we will go there and put our hands on it.

Who are some of your curatorial team members and what projects are they presenting?

There is Silas Miami who put together the film exhibition festival called Concepts of Freedom and the line-up is amazing. There is the talks program called Creative Dialogues put together by Mike Tigere Mavura. These programs are interesting and should not be missed. I also worked with Dr Bernard Akoi-Jackson and Gcotyelwa Mashiqa.

What can the public expect and take away from the first Stellenbosch Triennale?

I think the public can expect to see what they’ve seen before. However, they should expect to see it differently. The public should open itself up to new conversations and enter into a space that is not a gallery or an art fair. They can expect a completely new experience. If the mind is open, it will receive what has been put together for it.

This is very good then there is understanding for the artists, I mean the care I love the conversation thanks khanyisile

Much love from Uganda