This is not a feminist piece

It is a piece about coveted bodies – battered and slain

About plaintive throats begging, no, demanding freedom

This piece is about stolen pleasures in clipped clitorises,

And muffled voices resorting to the bodies that house them,

to speak on their behalf.

This piece will pay no mind to those who retort “Not all men”,

Because this is not a feminist piece

This piece is about life, defiance and survival.

(Inspired by Wana Udobang’s ‘This is not a Feminist Poem’)

The following imagined vignettes describe real-life experiences that many women around the world have been through. Often these experiences have been met with an aggression deep-rooted in patriarchy, such that women have been reprimanded or shocked into silence for fear of what might become of them in moments that follow.

In spite of this, some times these violations were too heavy to stay put within. They found their way out through the mouths of our mothers, sisters and friends, those who have walked various paths in life, and have become more assured in their steps. These stories also bear testimony to the ways some of our experiences have been transmuted into art by a number of bold artists.

“Human rights are not things that are put on the table for people to enjoy. These are things you fight for and then protect.”

Wangai Maathai

I

I am a 22-year old university student at the University of Benin in Nigeria. On May 27, 2020 I was found unconscious, on the floor of my church where I had worshipped for years. I was lying half-naked in a bloody pool my assailants made from by body using a fire extinguisher. When I woke, I could neither feel my face nor move my head. The church guard found me later that evening. My body was tortured and traumatised. I died not long after.

My name is Uwaila Vera Omozuwa and my killers have not been found.

‘Sanctuary’ is a body of work by Nigerian social documentary photographer Jenevieve Aken centred on the tragic story of Elvira Olandini. She was raped and murdered in the Italian village, Palaia in 1947. When her body was discovered, like Uwaila’s, it bore the mark of violence and a broken system. There were multiple stab wounds and a slit on her throat from which her last breaths might have escaped. Her killers were never found.

Aken developed this body of work during her residency program in Tuscany, Italy with Villa Fena Art Foundation in 2017. To tell this story she created ‘Sanctuary’ as an imaginative self-portrait performance series, portraying the spirit of Elvira who still roams the scene at which she was violated, refusing to rest until justice is served. These photographic works rendered in monochrome, force the viewer to reflect on the violence many women experience daily. ‘Sanctuary’ has been featured in several exhibitions including the 2019 edition of the LagosPhoto Festival.

“I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are different from my own.”

Audre Lorde

II

We are the girls in Owanto’s ‘Flowers’, those she speaks of and for. We had just approached our teens when we learned that to be fully accepted in our community, our bodies had to be cut and reshaped. To earn recognition as sexually mature women we lost a part of ourselves. We were readied for marriage through an excruciating rite of passage most of us dared not question. They said it was an important ritual needed to enhance fertility and help us stay faithful to our husbands. So we saw a mutilated vagina as a badge of honour. There were times the bleeding never stopped. We are the girls in Owanto’s ‘Flowers’.

‘Flowers’ is an ongoing project by Gabonese multidisciplinary artist and activist Owanto, which she began in 2016. It is a crucial work addressing the issue of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) that an estimated 200 million women and girls have gone through globally.

For this photography series, the artist has blown out analogue pictures of girls from a FGM cutting ceremony into digitised printed works on aluminium. In these images, Owanto veils the violation by removing certain sections deemed private replacing them with delicate hand-crafted porcelain flowers. Like a performative restoration to symbolically restore wholeness, rather than emphasise loss, Owanto explores the notion of healing, repair and transformation. When speaking about her work Owanto has said that the feminine, as creative energy, is a constant in the narratives she creates and is intimately linked to her childhood where women represent the pillars of the family.

‘Flowers’ was most recently shown in March this year at Sakhile&Me, Frankfurt.

“My own feminism is just human rights. I’m a woman who has rights to her own choices. I can do whatever I want whenever I want. It’s just that simple. If I were a man, it would be the same thing.”

Genevieve Nnaji

III

Let’s flip this script for a second!

I am a multi-millionaire with enough to buy all the kinds of men that I can have. One that dresses well, another with double six (six packs and is six feet tall), that will adore my curves and dripping handles without question. And if the third isn’t good in bed, I will get me another one. Oh! I will also have one endowed with enough husband material – 100% faithfulness, 80% hustling skill and complete with the virtues of the good book. A praying man, with enough grace to forgive my philandering ways on the days he catches me stray. Then I will remind him to be rather grateful. For thanks to me, he is a husband. Let’s flip the script for a second…

‘Area Babes and Ashawo Superstars’ is a digital performance work on Instagram by Oroma Elewa, in which she uses self-written memes visuals from Nollywood films as a framework for dialogue. Described by Koyo Kouoh as an unapologetic take on African feminism to shame patriarchy in its forms of control, abuse and manipulation, the women in Elewa’s series are seen negotiating life, sex, class and power in the 21st century.

Elewa uses her personal experiences to explore ideas that hold social, cultural, political, and racial relevance. She has a particular interest in contemporary womanhood and facets of Black identity, including the transnational African mindset, the diasporic experience, and her possession of a Black body.

IV

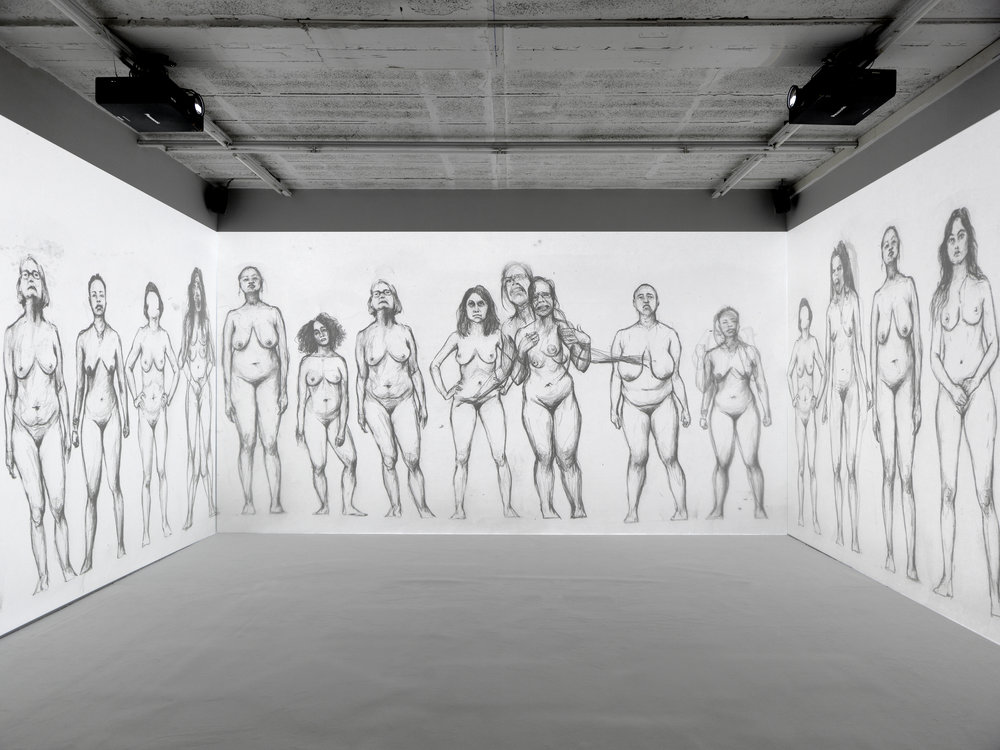

It is April 2017. We are walking along the walls in Tiwani Contemporary in London for an exhibition titled ‘For Every Word Spoken’ by Kenyan artist Phoebe Boswell. The nude large-scale pencil drawing is particularly triggering for my sister and I, as we remember a time we were the women in Boswell’s drawings.

It is a cold and wet morning in 2016. We are at the Rhodes University campus in Grahamstown, South Africa. Clad in jeans and headwraps, we are topless. The word ‘ENOUGH!’ is written across our chests.

We march in defiance, demanding that the university listen to our outcry to bring named rapists to book. If the local authorities won’t listen, then the country will through these televised protests.

It is the third day of the protests and the female staff have also joined in. Still, the authorities do not take us seriously enough. Instead of investigating the alleged sexual abuse offenders, they bring in the police to disband us and temporarily shut down the campus.

It is 2017 and the alleged offenders still roam free. We continue through the exhibition wondering how much louder we need to be to get them to listen.

‘For Every Real Word Spoken’ is an extension of ‘Mutumia’, a mixed media interactive installation. Mutumia is the word for woman in Kikuyu, however it is said that the word translates more directly as ‘the one whose lips are sealed’. Boswell created this piece in honour of women who have used their bodies in the absence of their voices.

‘Mutumia’ is a 30-minute looped wall projection of hand-drawn animation of an ‘army’ of naked women, going through various emotional states of protest. The projections are silent, but the floor is fitted with an interactive sound system of hidden sensors connected to soundtracks of women’s voices: a gospel choir, Kenyan women writers reading their work, a conversation with Boswell’s mother and a roll call of names of inspirational women. Working with women she knew and came to know, Boswell developed the work over a nine-month period, exploring the idea of protest through their voices and their bodies. In 2017, the work won her the Future Generation Art Prize.

“Society is obsessed with women’s bodies and I take my body back by doing whatever it is I want to do with my body.”

Malebo Sephodi

V

Do you think that this has been too much about our bodies? But it is always about our bodies. Do you find this a bit too much? Even when your mouths do not say it, your eyes are loud with your intentions. If you are not busy claiming it, you are telling us what to do with it. A Christian girl would need to pray the rosary to feel safe in daylight; a Muslim girl in a hijab and abaya is just as scared. Not even a schoolgirl is safe. Have you googled ‘schoolgirl’ in images lately? Then you should. No age is off limit.

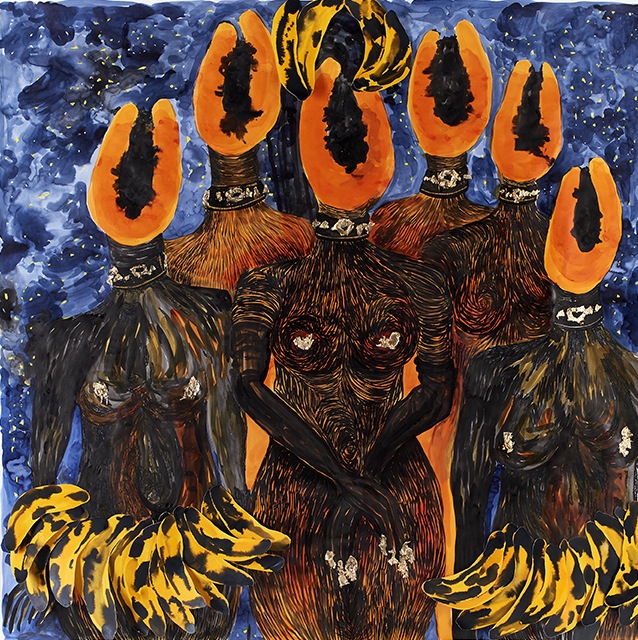

In ‘Lust Politics’, Lady Skollie creates playfully sexual paintings with bright colours, and visually symbolic fruit motifs. Exploring issues on sex, gender roles, taboos, objectification, violence, power structures, greed and lust; the suggestive images of bananas, papayas and repeated patterns of what she describes as pussy prints, highlight the artist’s anxiety towards unrealistic expectations of sexual and romantic relations between men and women. As a body of work ‘Lust Politics’ opposes female objectification and abuse from male-dominated establishments.

VI

The experiences are endless and the fight is never quite finished. But as the struggle continues, we will resist and we will insist, our voices will not tire. So in the future, long after we have gone, a new generation of women may look within and find the works of their foremothers there.