In these Covid stricken times, there is an undeniable irony in stepping away from digital screens to experience, in real life, an exhibition dedicated to digital art. Yet, that was, in essence, the proposition of Powerplay an exhibition held at arebyte Gallery in London, and organised in collaboration with the National Gallery of Zimbabwe where it is headed next.

Digital art is a latecomer into the pool of mediums that visual artists have at their disposal. It emerged in the eighties and has long suffered from its affiliation with neophytes and gaming. It is yet to thoroughly shake off the whiff of amateurism still attached to it. And even when a renowned artist such as David Hockney took to digital art to create portraits and lately a series of landscape drawings, the medium was still regarded as a side dish, a light-hearted art experiment beside his principal practice, painting.

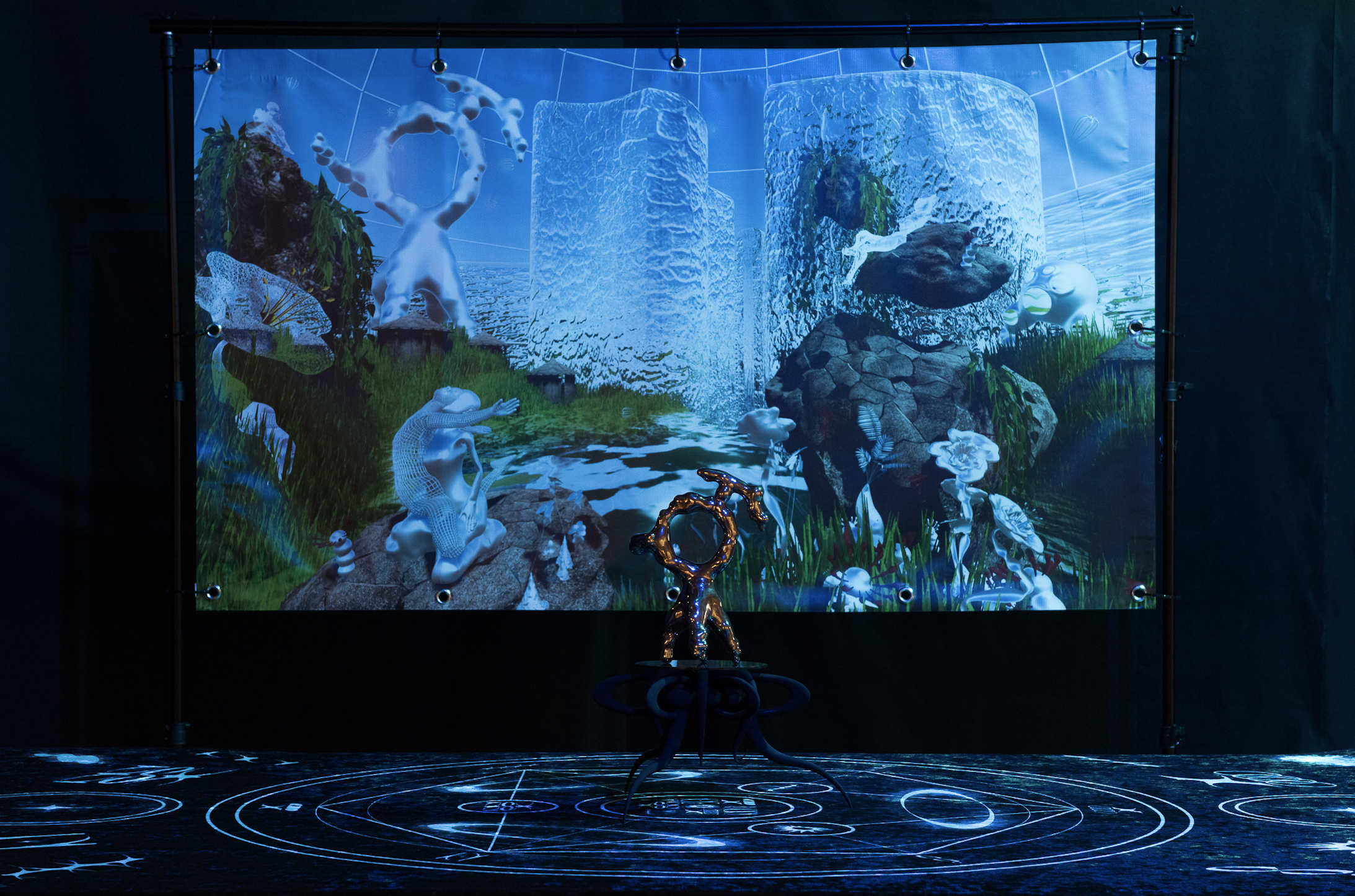

By contrast, the curators, with the title Powerplay, opted to lend gravitas to the exhibition from the outset. They also positioned the medium of digital art as the piece de resistance. It is the cornerstone of the creative practices of all the eight artists featured. The show examines the power dynamics at play across a broad scope of topics, ranging from representation to image-making, product making, cosmology, and mythology.

Powerplay opens with a spectacular rendering of the myth of creation by Nigerian artist and art director Niyi Okeowo. In his futuristic version of Michelangelo’s ‘The Creation of Adam’, cyborgs have supplanted humans. The two cyborgs’ bodies and pink halos shimmer against a contrasting black expanse peppered with small white stars. In this re-imagined Christian story of origin, God (distinguished by a pink cross on an outstretched arm) and her first creation are unmistakably female.

This opening work questions the normative roles of women and their representations in religious iconography. Its radical perspective becomes the common thread that binds together the various pieces of artwork in the exhibition.

Another standout piece of the show is Vincent Bezuidenhout’s video work. It mixes headshots of a Black man sporting a majestic turban with an image of a white woman wearing the colonial-era pith helmet. The images, blurry at times and playful at other times (blink and you will miss the twinkle in the man’s eye), evoke the racial stereotypes embedded in colonial photography.

To some extent, the enduring racial stereotypes that some African photographers, to this day, still challenge in their practices, can be traced back to these 19th-century photographs. Against that historical background, the exhibition unfolds with a reassuring sense that history may not repeat itself. This time around, pioneering African artists are early adopters of a new technology, set to disrupt and reshape the creation of visual narratives.

These artists are harnessing digital art to address racial issues and in the context of this exhibition, make visible the power imbalance deeply enmeshed in the fabric of modern societies.

You can catch a real glimpse of the exciting possibilities digital art can provide at the very end of the exhibition when you put on the virtual reality headset. Powerplay opens up anew, this time, within the grand architecture of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe.

Suddenly you can experience how the show would look and feel miles away in another setting, in another country, on another continent. As you move the joystick around and spring from room to room, you will stumble upon artist King Debs’s exhilarating work ‘Ritual Dance 001’. Press the VR control button further, and you will land at the heart of a solo dance performance. In this virtual space, animated calligraphic icons swirl around while the dancer comes alive, her body moving rhythmically along. A warm feeling of surprise and wonderment emerges from this strange sensation of standing within the performance. Of all the artworks reproduced within this virtual environment, the technology’s most transformative effect has been on ‘Ritual Dance 001’.

The teleportation, the ability to be physically in London on a grey and windy afternoon and simultaneously transported into the artist’s swirling dance, encapsulates the hopes and opportunities that this new medium opens for artists.

The curatorial choice to examine the equilibrium of power through a broad spectrum fittingly provided a range of experiences in the exhibition. However, it has left me feeling hungry for a more in-depth exploration of some topics. Although it is briefly addressed in the curatorial statement, the power imbalance that went unexplored is the one that underpins the medium itself: the access to technology and the other power, electricity in Africa. The issue will become particularly acute as the digital divide widens between urban and rural areas, or between the continent’s rich and poor countries. Going full circle, it remains to be seen what long-term ramifications these issues will have on art creation.

Since March, the art world has been forced to retreat online. It is a relief that this show has bucked the trend and remained a physical experience. Much of its narrative would have been lost in the pixelated world of the viewing rooms. Ironically, Powerplay has somehow reasserted the necessity for a complementary approach between digital and analogue worlds.

Powerplay concluded at arebyte Gallery in London on 26 September and is set to open at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe later this year.

Artists featured in the exhibition:

Niyi Okeowo (Mr Color)

Bolatito Aderemi Ibotola

Vincent Bezuidenhout

Oliver Hunter Pohorille (Scum Boy)

King Debs

Mbakisi Sibanda

Kumbirai Makumbe

Isaac Kariuki

Hanou Amendah is a writer based in the UK.