When revolutionary fervour swept across North Africa and the Middle East in the spring of 2011, city walls in the region began to carry messages of resistance and images of fallen frontline activists, as artists sought speak out against political repression in their countries.

Noting the creative response to the uprisings in their neighbouring countries, instead of scrubbing away spray-painted tags, the Moroccan authorities chose to encourage murals and other colourful street art, offering a legal venue for artistic expression.

But such a move did not signify the freedoms Moroccans had hoped for during the Arab Spring. In 2011, in an attempt to appease, King Mohammed VI announced extensive political reforms in the country on March 9, less than three weeks after the first street protests. This democratic period of political openness did not last long. Nine years later, Moroccan citizens and activists alike face restricted freedoms in speech, press, assembly and demonstration.

Over the years the Moroccan government has continued to support street art movements, rather than quash them, by sponsoring festivals organised by non-profit cultural associations. The largest of these include Jidar – Toiles de Rue, an annual event which gathers international and Moroccan artists in Rabat, and the Sbagha Bagha Casablanca Street Art Festival; both initiated by L’Boulevard, an organisation that supports contemporary music and urban culture in Morocco. The state has used the art form as a signifier of urban renewal in the country.

Graffiti, this contemporary form of expression which emerged on the streets of Philadelphia in the 1960s, and soon after on the subway trains of New York, became a way for the state to attempt to monitor any openly disruptive graffiti art movement in Morocco.

Inversely, in Egypt, in the years following the 2011 uprising, Cairo’s street art seemed to continue to embody the hope and audacity of the Arab Spring. The Egyptian revolution relied on street art in its various forms including songs, posters, performances, cartoons and most of all graffiti as a powerful vehicle for expressing dissent and resistance as well as helping articulate new visions of society.

The walls of Tahrir Square and Mohammed Mahmoud Street constituted a place where from 2011 to 2013, people would ridicule the president or the military. The phenomenon of frustrated young people channelling their feelings of injustice into making visual art is unique. Street art was the way they responded to police repression.

The public space…is now a police space in which the state tolerates neither resistance nor protest.

When Mubarak resigned after 18 days of protests, the streets of Cairo and other major cities in Egypt were flourishing with graffiti and street art. Graffiti works echoed the revolution and the revolution legitimised graffiti works. In his article ‘The Maturing of Street Art in Cairo’ for The New York Times journalist Josh Wood wrote:

‘In the six months since the Egyptian revolution began on Jan. 25, Cairo has emerged as the street art capital of the region, and its graffiti scene — one that primarily started with hastily scrawled slogans calling for the overthrow of the Mubarak regime — has evolved into one characterised by well-crafted motifs, both aesthetic and politically provocative.’

However free expression in post-Arab Spring Egypt has become increasingly dangerous. Legal and political authorities in the country made graffiti and other forms of street art a crime, pushing artists such as Ganzeer, who rose to the top of visibility among influential Egyptian street artists, to go into exile. The public space which art critic and curator Barbara Pollack wrote had “exploded with murals and graffiti that both mirrored the revolutionary spirit of the movement and propelled it forward”, is now a police space in which the state tolerates neither resistance nor protest.

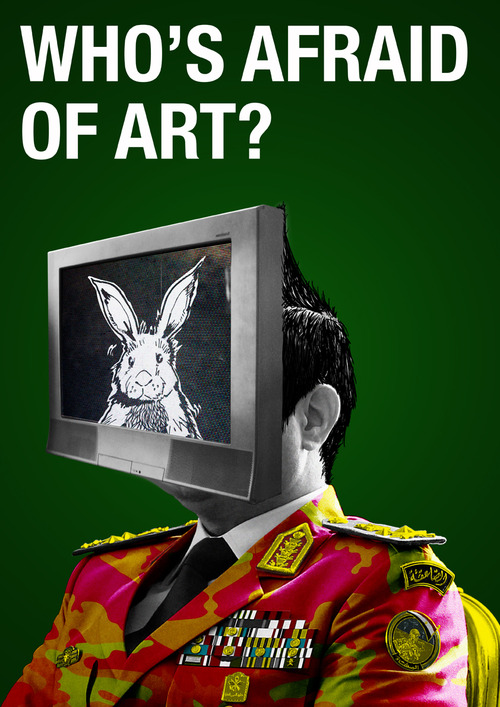

After Ganzeer participated in a global graffiti campaign against Sisi who was about to become the president of Egypt, a television journalist accused him of belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, a group considered to be a terrorist organisation by the Egyptian state. Ganzeer used his blog to post an image in which he replaces Sisi’s head with a television broadcasting a rabbit’s mug along with a letter addressed to the journalist. “What you’re doing makes him [Sisi], come off as a man who is very afraid of the impact of art. Rather than see us as a threat to the State, critical artists should be seen as a source of information to the State,” Ganzeer wrote in the letter which he significantly entitled ‘Who’s Afraid of Art?’ This post has been since removed.

In Morocco, some of the earliest expressions of modern street art and graffiti also took place in the 1970s. Artists Melehi, Chabaa and Belkahia decided to transcend the rigid boundaries of the museum and employ the street in the production of art. They displayed their artworks in Jemaa El Fna, the main square in Marrakech, and painted murals on the walls of Assilah, a town in the north of Morocco. These outdoor art exhibitions had the power to effortlessly and aesthetically engage the public through their manifest creativity, originality, and beauty.

As the idea of rule-breaking, which is crucial to street art, is absent in Morocco, one wonders does this contemporary form in Morocco still qualify as street art? It is argued, on the one hand that government “sanctioned street art loses its outlaw power to disturb and challenge”, urban ecologist and architect Paul Downton writes. But on the other, while some of its impact and power might be lost, a street artist is always pushing boundaries and confounding ideas of what’s possible even when they are not clandestinely using a can of spray paint.

Kharbachat is a street art event initiated in 2018 by Collectif Tzouri, an art collective comprising ten artists and established in Oujda (a city in the east of Morocco). The work of the group consists of painting a wide variety of large-scale murals in historically and culturally important parts of the city.

The huge portrait of an old man traditionally dressed greets you when you enter the narrow, streets of Sania, a neighbourhood in the old city of Oujda. The impressive fresco expresses the artists’ desire to decorate and reshape the material environment of this part of the city. It also brings vitality to the brutal reality of one of the poorest neighbourhoods of the city and gives political content to seemingly innocent street art.

Street art can thus only be understood in connection to what it exists within these relations. It is part of the architectural body of the city.

In 2009, the local authorities of Oujda ripped down Pasteur, one of the oldest modern schools in Morocco and replaced it with a public square. To denounce the destruction of the cultural heritage of the city, Collectif Tzouri made a series of murals representing emblematic figures of Moroccan art and culture on the bare, dull walls of the square.

The images work on two levels. At first glance, we see a tribute to a group of local artists who died recently, but if we look further and deeper, it is an image with various meanings that we discern. The artists reject urban greyness and offer a more colourful universe that symbolically repudiates the political corruption they perceive around them.

In his essay, Street Art: The Transfiguration of Commonplaces, philosopher Nicholas Alden Riggle, notes that the street is a key resource to artists of this practice the ability to speak to the city and develop an interaction with the public on the street and with the street itself is essential. Street art can thus only be understood in connection to what it exists within these relations. It is part of the architectural body of the city. Whether they are futuristic murals or stencils, street art works are artistic declarations which defy the norms of the gallery space and transform the city in a living work of art.

Commissioned or not, street art can be viewed as a revolution in a world increasingly urbanised and a protest against the different forms of spatial injustice.

Commissioned or not, street art can be viewed as a revolution in an increasingly urbanised world and a protest against the different forms of spatial injustice. The first graffiti writers in Philadelphia and New York subways, who came from impoverished neighbourhoods, resisted the conditions in which they were living by negotiating the spaces of their cities. Moroccan street artists are too producing their own space to meet their needs and claim their right to the city¹. Although their works do not pose a threat to law, order and security, they can be viewed as a collective resistance which reflects conflict over meanings and values as well as differences in the understanding of what and who public space is for.

Roksy and Drobys are two artists who decided to contribute to Casablanca’s nascent street art scene. Both women recognised the empowering and emancipatory potential of this form of artistic expression and although they did not follow the same itinerary, they work together on their street art projects. Roksy, whose name brings to mind the wild, rebellious spirit of rock and roll, is an illustrator who trained in mechanical engineering, then at the School of Fine Arts in Casablanca where she majored in comics. Drobys on the other hand is a self-taught artist who had no formal art training.

Interweaving graffiti and cartooning, both Roksy and Drobys’s chief objective is to defy the spatial hierarchy that organises patriarchal Moroccan society. Although both male and female street artists transgress boundaries, they do not experience the same kind of transgression. Though all artists have a subversive narrative to tell in a public space women have the added struggle to be accepted in a male dominated space. Moreover, women do not always have the opportunity for training to produce large scale figure paintings. And so Roksy and Drobys had to discover a way to stand out and separate themselves from their male counterparts.

The two work with various media — stencils, paint, paste-ups — and incorporate cartoon figures in their murals, thus creating a uniquely personal style. Giving a public face to the characters of a comic book, a literary genre that is still considered marginal in Morocco, they are challenging their own marginality as female street artists and pushing their graffiti into new terrain.

In his book Theorizing Power political and historical sociologist Jonathan Hearn writes:

‘There isn’t one model of Resistance that is conceivable—solitary, spontaneous, concerted. Resistances can be possible, improbable, violent, savage or necessary. The form they take cannot be absolutely defined due to their transitory and changing nature, but the enduring characteristics of resistances is that they are intricately connected to exercises of power.’

In an epoch in which public space is increasingly policed and under surveillance, Moroccan street artists have the opportunity of investing, shaping, dominating space and claiming the city as theirs. Occupying the streets and using them for personal expression gives their work a subversive character and transforms it into a form of dissent that people in power are generally afraid of.

Graffiti provides alternative ways of connecting to the city for those who write or paint on walls but also for those who read and see it. It replaces the advertising images that fill the walls of the post-industrial city with impressive large-scale wall paintings which often convey a message of unity with beauty and colour.

Once in the street, artworks are owned and overseen by passers-by. They take on a life of their own, independent of the intentions of the artists.

As street art is also associated with disadvantaged communities and ignored parts of the city it can transfigure the most marginalised neighbourhoods and offer recreation and distraction from overcrowded and unhealthy housing.

Even if commissioned, state funded, and not overtly political and critical or dissident, it expresses artists’ need to express themselves, to own the walls of the city, to remould the urban space and to recreate their reality.

Once in the street, artworks are owned and overseen by passers-by. They take on a life of their own, independent of the intentions of the artists. Their public appropriate them differently, assign various meanings to them, and physically alter them by modification, reproduction, or destruction.

“Street art weaves art into everyday life,” Riggle writes, and thus invents new ways of being and living in the city.

Chourouq Nasri is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Letters, Mohammed 1 University, Oujda, Morocco. She is also a member of the Identity and Difference Research Group.

¹Lefebvre asserts the right of people to a form of participatory citizenship. This is what he calls, ‘the right to the city,’ a concept he developed in the late 1960s.