Over the last few weeks, the global art world has fallen into a semi-conscious slumber. Gallery openings, talks, dinners, art fairs, biennials – the life and blood of this discourse and commodity-producing machine – have been postponed or cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This is a quick, unprecedented turn of events in an industry that has often equated bigger and faster with better. For this very reason, some have adopted an optimistic attitude toward the pandemic, believing it to be the catalyst for a fairer, more sustainable, more collaborative art world.

The stay-at-home policy that various governments have introduced in response to the health crisis has been viewed by many as ushering in a much-needed period of existential reflection for millions of people (that is, for non-essential workers). Some have even pointed to the rise of podcasts, online panels, free editorial content, and virtual viewing rooms as the early beginnings of a more accessible, democratised art world.

The positive changes that could come out of this pandemic sound pleasurable to any ear desperate for social transformation. However, we ought not to forget the great degree of uncertainty it has created for several artists, educators, curators, and the like. Income streams for many art workers have been compromised by recent commercial and institutional closures.

I spoke with five artists, all African and living outside the continent, to get their perspectives on this strange time: how they’re responding to the lockdown, both as consumers and producers of culture; how their current and future plans have been affected by the crisis; and what kind of world(s) they imagine could form post-pandemic.

“The Figures series talks about the circulation of populations but also the circulation of ideas, of goods, of culture, many things in fact … It looks like the [recent] restriction of circulation has had an impact on all these global connections.”

Malala Andrialavidrazana

Andrialavidrazana is undergoing the global lockdown in Paris, where she’s been based since the early 1980s. The Madagascan-born multimedia artist, whose work engages with themes of globalisation and cross-culturation, mentions “I had the feeling recently that the only way to look at the world is through screens, through media, but they’re all showing the same images wherever you are. So, I feel like I live in a bubble”. Having been in lockdown for almost 50 days, Andrialavidrazana went into isolation before it became official French policy, following a trip to Brussels for a group exhibition.

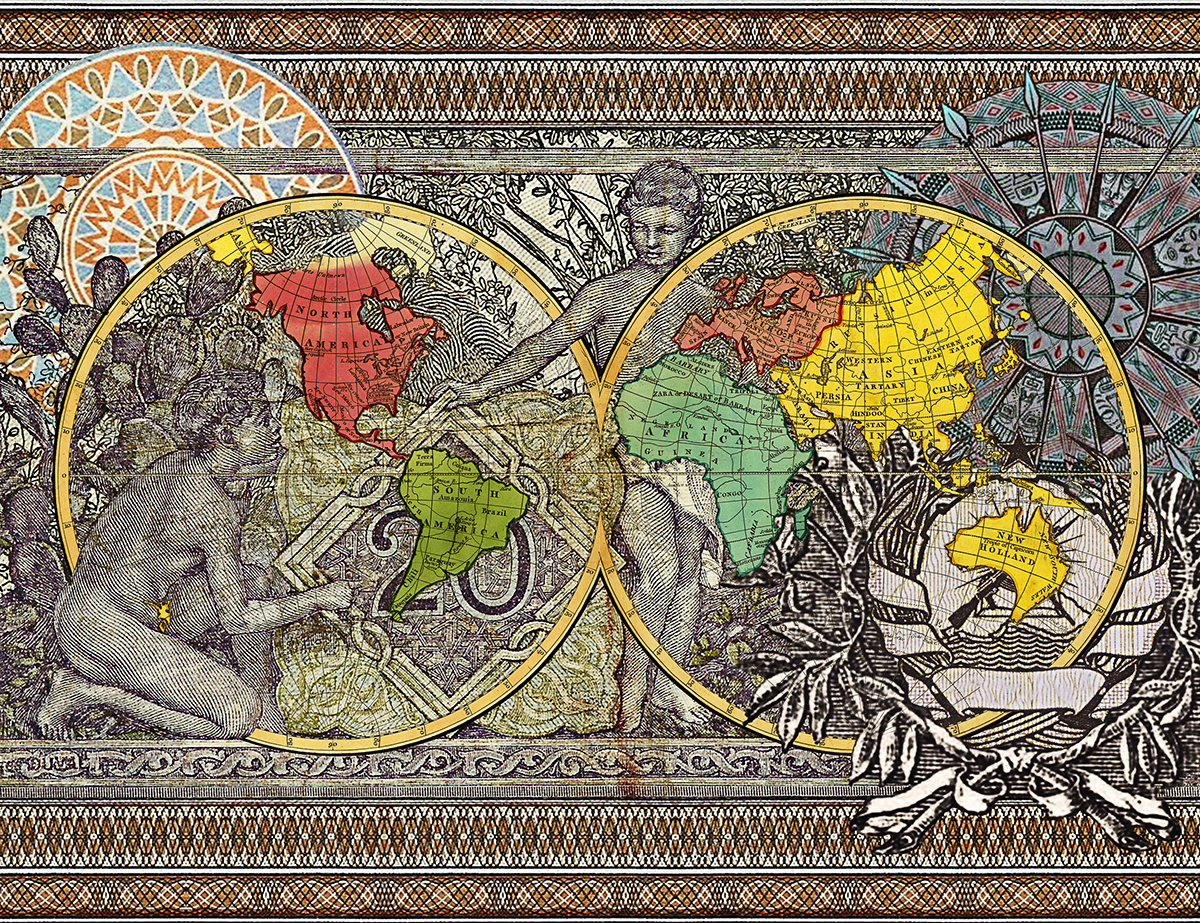

After spending a few days cleaning her place, Andrialavidrazana “decided to take care of a big part of [her] archives”. Since 2015, she has embarked on a series titled ‘Figures’ – vivid photomontage compositions, resembling 19th-century cartographic illustrations, that seamlessly combine disparate visual materials cut from banknotes, world atlases and album covers. Fortunately, Andrialavidrazana sources much of her archival material from family members and friends, instead of public libraries and museums (all of which are now closed). She also acquires her visual materials from frequent international sojourns, adding “of course, I cannot travel at the moment but I have enough material from previous travels that I can work with”.

The rapid spread of the Covid-19 virus makes evident the extreme interconnectedness of the world, something Andrialavidrazana’s work has long alluded to. “The Figures series talks about the circulation of populations but also the circulation of ideas, of goods, of culture, many things in fact … It looks like the [recent] restriction of circulation has had an impact on all these global connections”. She’s nervous that the pandemic could be instrumentalised by far-right politicians – who’ve been growing in popularity in Europe over the last few years – to legitimate their xenophobic, nationalist rhetoric. But ultimately, Andrialavidrazan believes that “we [the art world] have to be united to get out of this”.

Her exhibition at the Boghossian Foundation in Brussels, ‘Mappa Mundi’, focusing on artistic representations of maps and borders is currently closed with plans to re-open on May 19. Most of the artist’s other projects have been postponed for the time being.

While tending to her archive (composed of 7,000 images), Andrialavidrazan has been watching a documentary series on the history of drug trafficking and listening to disco music.

“The art world would not exist without artists … The fact that so many artists may not be able to pay their rent after a month and a half of quarantine shows that something is wrong with the power structure of the art world…”

Adama Delphine Fawundu

Fawundu is based in New York, the city hardest hit by the coronavirus. The artist recounts the quick escalation of the city’s response to the virus: “Everything happened so fast. I came back into the country [the US] from Germany at the end of February … by the end of that week, we got a notice that classes were going online (Fawundu teaches at Columbia University) … there was a buzz that something is happening but at no point did I really think that it was going to keep us inside.”

Since the lockdown began, she has stuck to a strict food regimen to build her immune system, consuming non-processed foods such as smoothies and porridge. She’s also added morning exercises to her daily routine, even participating in Deepak Chopra’s 21-day meditation challenge; an activity that has resonated with the radical love poems she’s been reading, which come from the Islamic Mystical Tradition. “It made me realise that there’s something bigger than all of this … and about the endlessness of the universe, which makes us very small”.

Born in Brooklyn to parents from Nigeria and Ghana, Fawundu’s photography and video-based practice explores the multiplicity of the African diasporic experience. Often incorporating hair and water into her work, she transforms these materials into metaphors for the historically thick connections and rhizomatic migratory flows of the black diaspora. The health crisis has added a new urgency to Fawundu’s practice, giving a “practical” layer to her primary interest in the “spiritual nature of things”, as she reconciles her prior mystical representations of natural phenomena with lived ecological realities.

Fawundu has also been reading Octavia Butler’s Kindred with her son as well as academic literature on the work of Anton Wilhelm Amo – an 18th-century Ghanaian philosopher who was the first known African to attend a European university and pursue an academic career in Germany. The overlooked Enlightenment-era contributions of Amo informs “The Faculty of Sensing”, a group exhibition curated by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung at the Kuntsverein in Braunschweig, that includes Fawundu’s latest work.

The exhibition features her short video work, Sunsum, In Spirit (2019), which like her other videos are composed of spontaneous footage accumulated over a few years. “Even now when I go out, I’m always recording whether it is my cell phone or my 35mm camera.” Fawundu has also been recording her phone screen, observing that “it’s never looked like this before”.

Unfortunately, many of the artist’s plans have been interrupted by the pandemic: a talk in Greece, a re-visit to her exhibition in Germany, a music festival in Toulouse, holidays in Spain and Nigeria, and an upcoming exhibition in Abu Dhabi. Thinking about the world (and specifically the art world) post-crisis, she says “The art world would not exist without artists … The fact that so many artists may not be able to pay their rent after a month and a half of quarantine shows that something is wrong with the power structure of the art world … hopefully, this pandemic sheds light on the fact that dismantling social hierarchies makes us stronger as a people”.

Besides being in contact with members of MFON (an organisation co-founded by Fawundu centring black female photographers), she has been at work on her first monograph.

“The reality of what is happening now is revealing [something about] human behaviour, the danger of capitalism, and the danger of how entitled we feel”.

Abraham Oghobase

“In a way, I’ve always been in a lockdown mode. For me, it was a very organic shift. I’ve always worked in a confined space both mentally and physically.”

Oghobase moved to Toronto from Lagos very recently. The photo-conceptual artist, although seemingly well-adjusted to the lockdown lifestyle, misses the company of friends, the in-person exhibition experience, and his direct access to specific art materials.

Oghobase has adopted a positive attitude toward the crisis, viewing it as an opportunity to slow down and reflect. He has been absorbed in many books, ranging in topical scope from photography and curatorial practice to theory and literature, including Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung’s “In a While or Two We Will Find The Tone” and Toni Morrison’s “Burn This Book”. “I’ve always thought about the power of words in relation to the power of visual art, to the power of my practice … There are no differences, no hierarchies, in terms of form, but there can be connections … everything you see including architecture, visual art, literature is a function of space, time, rhythm, colour, texture.”

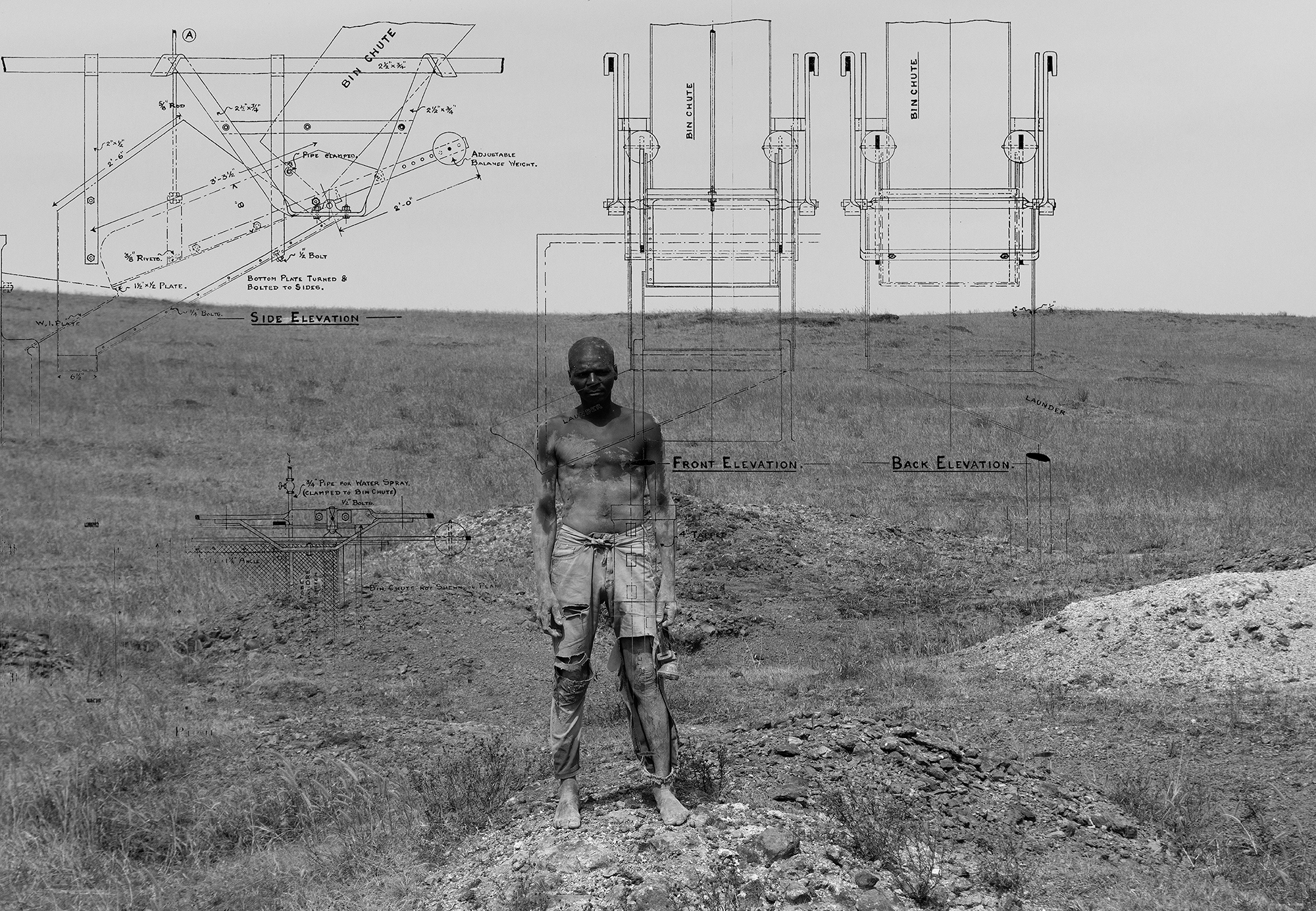

“The reality of what is happening now is revealing [something about] human behaviour, the danger of capitalism, and the danger of how entitled we feel”. Oghobase’s work often meditates on the African postcolonial condition, mobilising the poetics of spectral imagery and the textures of delicate, translucent materials to reveal repressed layers of affect behind dominant and objectivised historical narratives. His recent series, Layers of Time and Place: What Lies Beneath (2017-), focuses on Nigerian landscapes haunted by British colonial extraction (an exploitative capitalist history, I might add, that has framed many governments’ necropolitical responses to the pandemic).

With regard to a post-pandemic world, the artist is ambivalent. He acknowledges that technological disruptions could bring forth positive changes, in terms of re-thinking former structures of social organisation, such as the office space. However, he worries that future generations, having an attenuated memory of the pandemic, could repeat the present generation’s mistakes.

Oghobase was part of a group exhibition, “Layers”, curated by Iheanyi Onwuegbucha and Valentine Umansky at Labanque Béthune in France, which was forced to close. His upcoming exhibition at Kadist in Paris has been postponed till next year as well as a residency at the Kai Art Center in Estonia. Luckily, he still has an exhibition to look forward to in October at the Allcott Gallery, in North Carolina, which he is currently creating a new body of work for.

“I’m especially curious to see what happens to black artists after this…”

Florine Démosthène

Démosthène is living through these strange times in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where she’s been based for the last two years on a fellowship. The Haitian-born artist was in New York in early March for “art week” but decided to return to Tulsa, where she could be close to her studio. “It’s much better here than in New York because at least you can go outside … you’re not really running into people and it’s really spread out, but May and June is tornado season so we have that”.

Unfortunately, Oklahoma’s lockdown measures led to the closure of the fellowship’s studios so Démosthène has been making work in her apartment; she’s made four slightly smaller pieces in the last few weeks. Démosthène’s multimedia paintings and collage work, which depict otherworldly, “shapeshifting” figures question the flattened (aesthetic and ideological) representations of the black female body. Unable to separate her workspace from her domestic space, the artist confesses “I kind of sleep in chaos … I’m working with glitter and it gets like everywhere”.

Curious as to how the pandemic has affected her normal lifestyle, the artist replies “Honestly, it’s not any different for me because I’ve been working in the studio for two years nonstop”. Prior to her fellowship in Tulsa, Démosthène was based in Accra, Ghana, for three years, an experience that, though enjoyable, proved to be “physically exhausting”. She has taken the last two years in middle America as an opportunity to “decompress”, which the lockdown has actually facilitated.

Démosthène has avoided the internet and any superfluous communication, instead using this time to reflect on her past work and strategize how she can move forward with her practice. For example, she has been considering ways of incorporating three-dimensionality and the public sphere into her work. “I’m interested in artwork beyond the gallery walls … something more interactive, like a collective gathering. I’ve been looking at masking ceremonies in Togo and Benin”. The artist has also been reading a lot of Nigerian literature, cycling on her new bike, and essentially engaging with “anything that doesn’t have to do with Covid-19”.

Démosthène’s upcoming residency in New Orleans at the Joan Mitchel Foundation has been postponed although her residency in Lagos at the Arthouse Foundation is still planned to go ahead. Asked on what kind of (art)world she envisions post-pandemic, the artist believes “a lot of galleries are going to have to close” (especially the smaller, less digitally-savvy ones). She is especially “curious to see what happens to black artists after this” given that collector’s tastes and budgets are likely to become more conservative in response to the global economic downturn.

“I’m hoping [for] a more creative world … a more creative approach to life…”

Samson Kambalu

Kambalu is on lockdown in Oxford, where he teaches at the Ruskin School of Art and is a fellow at Magdalen College, Oxford University. “The first thing I noticed was my shows being shut”. The Malawi-born writer and conceptual artist is referring to his solo exhibition, “Postcards from the Last Century”, at PEER in London; a group exhibition, “History Without A Past”, at Mu.ZEE in Oostende; and this year’s FotoFest Biennial, “African Cosmologies” in Houston. Kambalu usually makes work in the College’s studio but, due to the pandemic, has been working mostly from his home in Summertown.

Kambalu echoes the sentiments of many other artists in this piece saying “For an artist, life is always kind of an emergency already. This lockdown changes things in that I can’t travel as much I’d have liked, but an artist works alone a lot”. Indeed, the artist’s turn from painting to conceptual, often installation-based, art was inspired by a prior pandemic – the HIV/AIDS crisis in his hometown in the 1990s. “There was death everywhere … and it drove me to a lot of thoughts, so I made this football plastered with pages of the Bible” (Kambalu is referring to ‘Holy Balls’, a recurring work in his practice). His politically informed, intellectually rigorous work has thus been long driven by the conditions that frame our current moment. He wryly states “I think the world has come to me”.

Kambalu is known for his less-than-one-minute silent videos (what he’s termed “Nyau Cinema”) which, typified by sped-up motion and a grainy, sepia-tinged aesthetic, cross-reference early cinema (à la Charlie Chaplin) with 20th-century European avant-garde techniques. Remarking on the abrupt brevity of his films, he remarks “The cuts you see in my films are the cuts of history”. His approach is also highly influenced by Nyau philosophy – a set of cosmological beliefs indigenous to his home country – explaining how its principles (expressed through masking traditions) complement the theories of many radical European thinkers, from Martin Heidegger to Guy Debord. Nyau’s idea of time, which is unlike the West’s linear conception and more akin to “a series of ruptures”, both animates his work and aptly describes this unprecedented period of swift, disjointed, structural change.

The artist has been reading a lot of philosophy, in particular, Slavoj Žižek’s The Plague of Fantasies and The Ticklish Subject. “His argument is simply that you can’t have life without the excess of negativity”. He has also been watching the films of Spanish director, Luis Bruñel, and listening to Blues music, saying “I hear a lot of Africa in them … what makes the Blues is the varying imperfections”.

Kambalu has also been at work, composing his flag-like images, which resemble the bold, abstract geometric patterns of many African postcolonial flags. He is considering filming in his local environs, whereas he would typically film during his travels. These improvised acts of spontaneity and re-adjustment are nothing new for the artist who says of his work “It was built around trying to make the most of bad situations”.

Kambalu hopes that the pandemic will form “a more creative world … a more creative approach to life”, one where increasingly flexible forms of work and government-funded art initiatives become the norm. “I find this time interesting. For me, this is it”. He is quick to mention that he does not wish for anyone to die, but he believes that the pandemic has jolted us into a state of urgency, which could lead us to make the kinds of changes that have been long overdue.