Roli O’tsemaye reviews “[Re]entanglements: Contemporary Art and Colonial Archives” by Kelani Abass and Northcote W. Thomas, showing at the National Museum, Lagos.

At the exhibition “[Re:]Entanglements – Contemporary Art & Colonial Archives” at the National Museum, you will encounter mixed-media paintings by Kelani Abass of people who would have been at least 150 years old if they were still alive. You may find these people, whose heritage trace down to the present-day Edo region of Nigeria, staring back at you, preoccupied with mundane activities, or simply sitting listlessly. You may even find yourself wondering if one of these people, sometimes having a confident poise and sometimes with a certain gloom hovering over their face, is perhaps your ancestor.

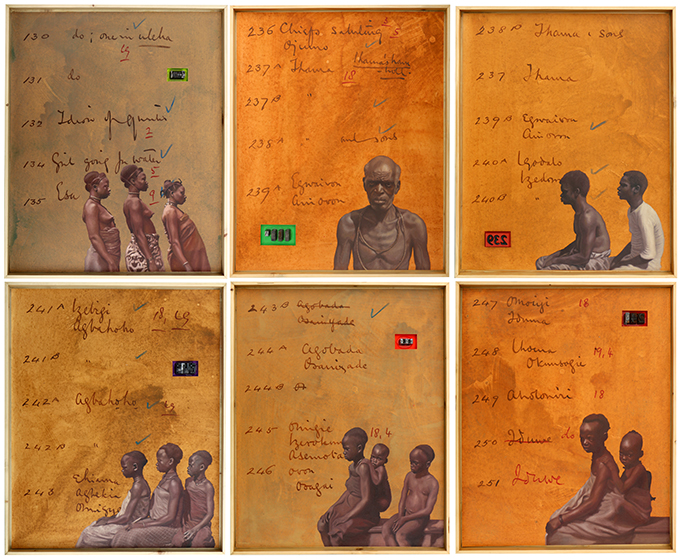

These mixed media paintings, twelve in total, are produced in acrylic and oil in a uniform small-scale size, with their backgrounds set in a light yellow hue. They have numbers, names and symbols that appear in rows on the canvas. The most significant numbers are those derived from a letterpress machine that the artist has embedded in the paintings. In tracing the numbers, you will discover, for instance, that two boys seated in one of the works with the number ‘248’ were called ‘Ihowa’ and ‘Okunbogie’. The process of creating this series which Abass titled ‘Colonial Indexicality’, took several coatings of light acrylic, done intermittently, to achieve the kind of background that reflects the time these images represent. They are also consistent with the artist’s painting style evident in most of his works, as the paintings have a smooth finish that veils the markings of the brush.

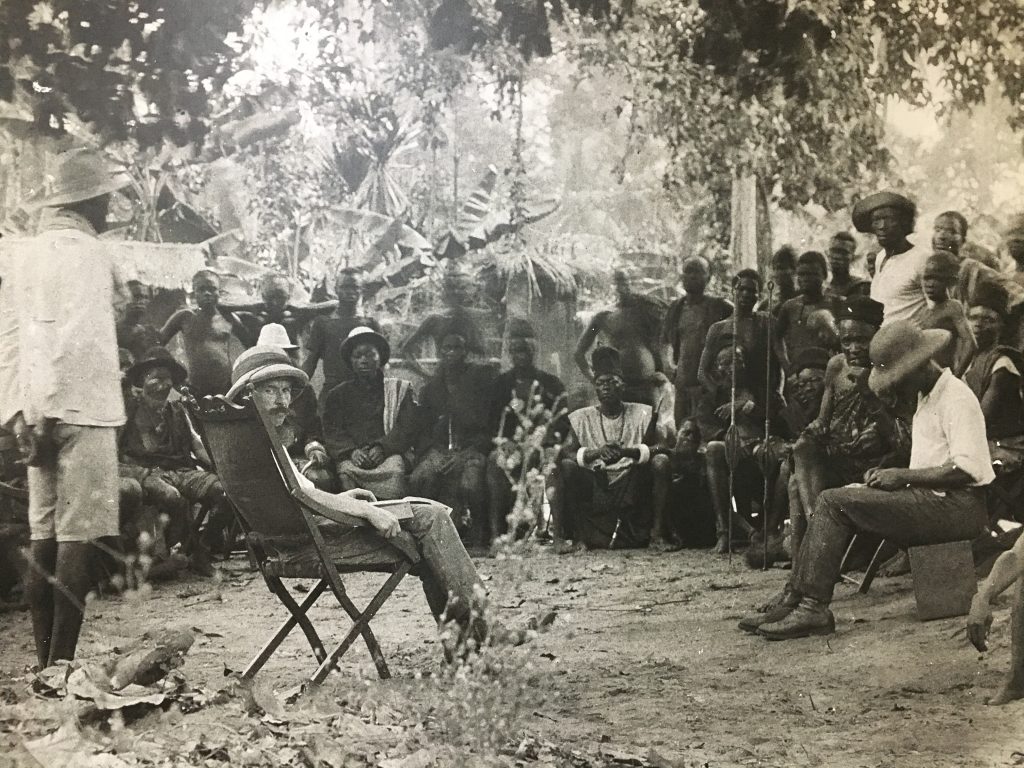

The source of these paintings is a rare, old photo collection dating back to between 1909 and 1913. At the time, the British were heavily present in the region and had appointed Northcote W. Thomas as the first anthropologist to survey one of their colonised territories. Thomas documented in photographs, sound recordings, numbers and jottings carrying the names, events, and locations of different people. These survey documents were discovered recently. Through a project called “Re-entanglements”, led by Paul Basu, a professor of anthropology at the SOAS University of London, people from different fields of study, including artists, are invited to engage with these materials to understand the historical context and significance of the archive in the present.

In July 2019, the first “[Re:]Entanglements” exhibition in Nigeria took place in Benin-City. It featured works by fifteen young artists who responded to the archives individually and in their preferred media. Abass’ engagement is the second exhibition in this explorative journey that will culminate in a grand exhibition in the UK, in 2020.

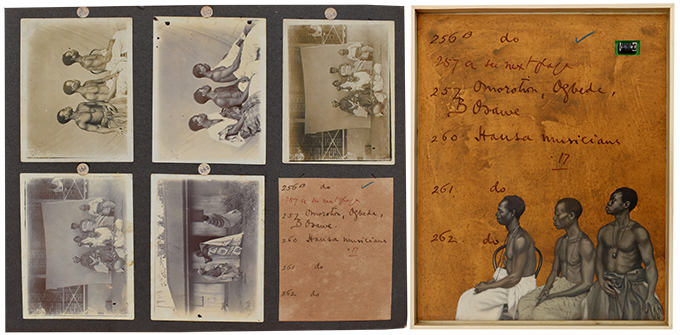

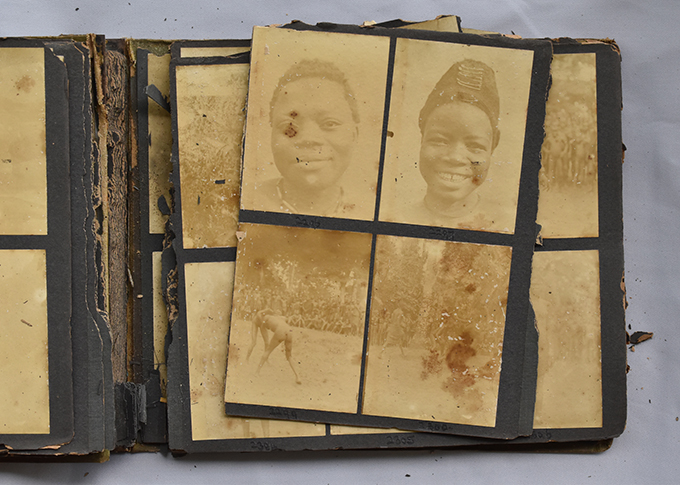

Although most of these discovered materials were kept, buried, hidden, or preserved (depending on who is telling the story), in some archival museums in the UK, like the Pitt Rivers Museum, The British Library Sound Archive, and University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, there are sixteen of the photo albums that have somehow survived time at the National Museum in Lagos. Over time, and because of the lack of resources to properly preserve them, the albums have become fragile. But, in spite of their current conditions, a number of the albums are positioned at central points in the exhibition, protected by glass. Visitors are encouraged to view them but are not allowed to touch. It is from these albums that Abass found the images of the people who now have their replicas painted or printed on canvas and paper in the exhibition.

The monochrome images, printed on canvas, extend beyond Edo people to the present-day Delta, Anambra, and Rivers states. The sources of these works are not limited to images from the National Museum’s archives. One of the works, occupying a significant amount of space, is an image from the Royal Anthropological Institute. It shows Northcote W. Thomas sitting in the middle of an open-air meeting with people from a community seated around him to discuss a land dispute in present-day Anambra. Other large-scale images include a coronation dance from Awka, a market in Nise, and a courthouse in Nri. The works extend into a second room with blue walls, which heightens the melancholy the viewer may already feel. These images stir at you as the others encountered. You will further appreciate or curse at the evolution of time, evaluating the similarities as well as the differences between then and now. You will marvel at the brazen nudity of people in some of the pictures – how it looked normal at the time, and how some of the hairstyles still bear semblance to the varieties seen today. Also lurking amid your assessment, perhaps, are questions about their faith and fate. Did these people struggle with saying the Lord’s Prayer and chanting traditional litany in their mouth at the same time?

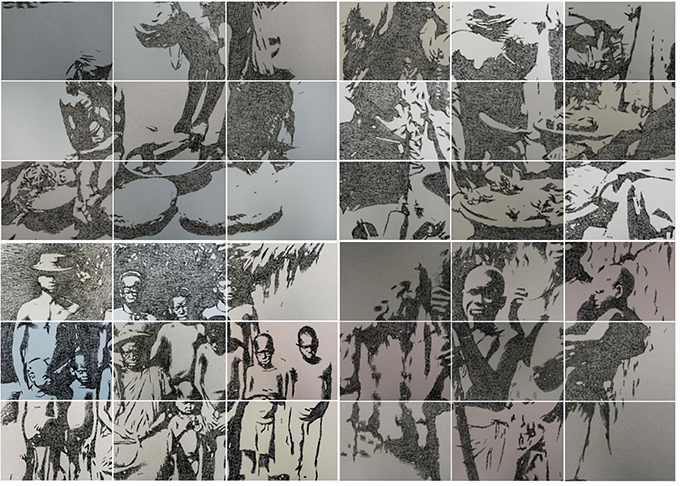

As you progress through the works in this room, your reverie will be interrupted as another series, the ‘Stamping History’, comes into view. In this second body of work under ‘Colonial Indexicality’, Abass shows sheer skill in draughtsmanship—his obsession with precision, and his unceasing fascination with numbers make a grand impact in this series. Again, in this space, he has contrasted images from the original archives with his rendering, and from a distance the works seem like a simple drawing. On closer inspection, you will see numbers flesh out discernible forms from Thomas’ images. How he achieves this is almost genius. He describes the process as a “performative oeuvre” reflecting the relationship between the manual and mechanical process that goes on behind the scenes in printing. These works, comprising of five interlinked drawings, have been painstakingly made by stamping the hand-numbering machine.

Numbers have been a recurrent motif in Abass’ works. You will find them in past works like Asiko (Calendar) and Stamping Histories series, which were first exhibited at the Centre for Contemporary Art in 2013 and 2016, respectively. The numbering element alludes to Abass’ family history and childhood. His parents ran a printing press business. When he returned from school as a child, the artist and his siblings assisted their parents at work. Part of the job assigned to him was to manually stamp numbers on the invoices made for clients with a hand-numbering machine.

The numbers used in the ‘Stamping History’ drawings were not dispensed capriciously. In going through the archives, the artist observed the sequence Thomas used in recording in the albums. For example, he saw 1155 in the album for an image he recreated, so began with a corresponding number in his drawing. Also, because the machine is automatic, the numbers progress sequentially. He achieved the complete drawing with over 80,000 combinations, and the final number is 85,867. The grid-like arrangement of the five drawings, which resembles a jigsaw puzzle, mimics the arrangement of the photographs in the album. It speaks to the fragmented form of the archive which was pieced together to make sense of the information gathered. The drawings, created on archival paper, are best appreciated when you step back to see the forms reveal actual people: sitting women, a group of men from varying generations and people engaged in domestic activities. They resemble the negative copy of vintage pictures.

As you reflect on the works, you will appreciate that they took about a year to create. Abass has not only succeeded in re-documenting history, using materials that hopefully should endure time but has also succeeded in retaining the archaic effects in Thomas’ works. The coming generations will engage these works and see up close a sizable vignette of the past showing people, who once lived, with whom we share a common national history.

“[Re:]Entanglements – Contemporary Art & Colonial Archives” at the National Museum, Lagos: September 21 – October 21, 2019. Later extended to October 28, 2019.