Our series on African artists navigating through the pandemic continues with experiences from Evans Mbugua, Ibrahim Mahama, Temitayo Ogunbiyi, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Tizta Berhanu, Moufouli Bello and Bright Ackwerh.

It has been over six months since the COVID-19 pandemic brought about a disruption to the order of things; ushering in an era that saw most people learning afresh, ways to live and ways to negotiate, and in some cases make demands, for their survival.

In recent weeks, the world has been forced to confront certain realities and issues such as racial discrimination and the many adverse effects of capitalism, which continues to expand the gap between the haves and have-nots. One way this was unveiled was in the recent #BlackLivesMatter protests, which started in the United States but continued around the world.

With the coronavirus outbreak upending many social and economic sectors including the global art scene, the ecosystem has had to adapt, seeking alternatives in the digital world. In the midst of the pandemic, still holed up in our various homes, we asked some contemporary African artists, mostly living in Africa, how their lives and practices have been affected by the pandemic.

On June 5, 2020 Kenyan artist Evans Mbugua, would have returned to Paris from Dakar, after his participation at the Dak’Art OFF exhibition – one of the features of the Dakar Biennale of Contemporary African Art. Unfortunately, he was unable to even leave Paris. As with many other art programs, fairs, exhibitions and festivals around the world, Dak’Art 2020 was cancelled due to the quickly-spreading coronavirus.

“This was to be my first experience at the Dakar Biennale,” Mbugua states. “I was very excited about it and had been working since the beginning of the year towards this. I was going to present a new body of work as a series. I had prepared works that were going to be linked to the Dakar/West African tradition of painting on glass.”

Resident in France, which was one of the most affected countries in Europe, and having had to tend to his wife who exhibited COVID-19 symptoms, Mbugua understood well the implications of being infected with the virus. So, when news came that the virus had spread to Africa he warned his family in Kenya not to take it lightly and that it wasn’t a rumour, the virus is real and life-threatening.

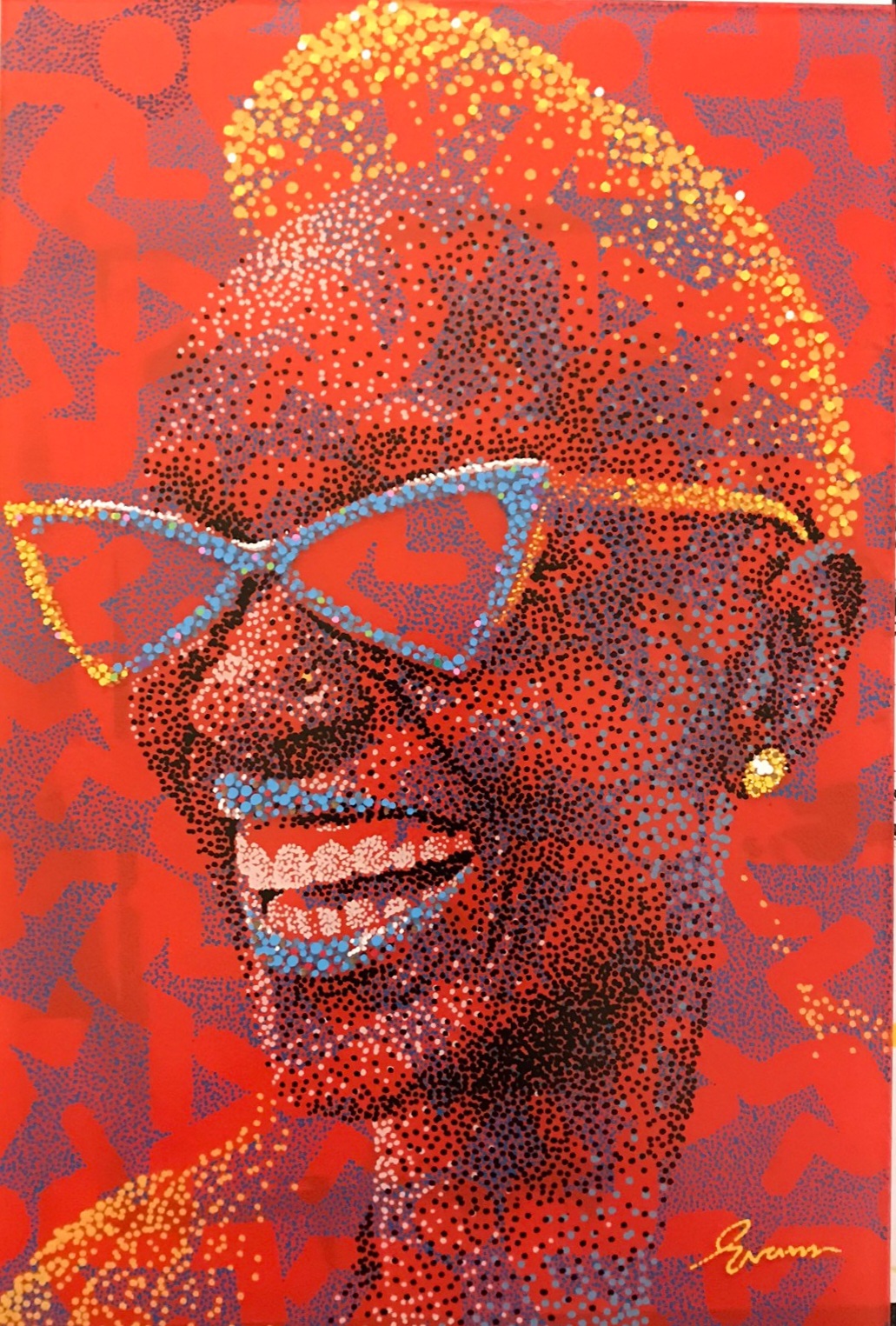

Mbugua is known for his vibrant portraits against patterned backdrops, which he lays underneath Perspex glass to enhance the reflection of light on his subjects, emphasising human frailty. At the Dak’Art OFF exhibition, Mbugua was to present 40 artworks, all bearing political connotations. Titled in French as Parfois, Il Vaut Mieux Rire, (At Times You Better Just Laugh, in English), the idea was conceived from the general attitude of people to laugh when talking about serious issues. “These works are portraits of people just laughing,” Mbugua describes. “And all the titles of the art pieces were given ironically speeches most politicians make.”

Finding humour and sharing jokes about the pandemic with loved ones, attending artist talks and other virtual events on social media, are some of the ways Mbugua found relief and distraction from the incessant news about the coronavirus.

“During the pandemic, we have realised that people are adapting more [towards] a socialist system, than a capitalist system…”

Ibrahim Mahama

Renowned Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama, had a slightly different experience. When the travel ban began he was in Australia where he was participating at the Biennale of Sydney, which had to close abruptly barely two weeks after its opening. “I was lucky to get home a few days before the borders were shut in Ghana and Australia. Upon my return, I quarantined for some weeks and after that, I travelled up north to Tamale in Ghana, where I am working on the studio, which I had decided to concentrate on during the period,” he says.

Prior to the lockdown in Ghana, Mahama and his team had film screenings for the local community in Tamale, where he has built the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA), but had to discontinue temporarily due difficulties they would have faced adhering to social distancing regulations.

In his practice Mahama examines issues of inequalities and marginalisation in capitalist systems using materials as a medium of expression. At the Biennale of Sydney he presented two installations: A Grain of Wheat, which is an assemblage of medic stretchers he collected on a research project in Athens, Greece, and produced during his residency in Berlin, and No Friend but the Mountain, made from charcoal jute sacks, metal tags and scrap metal tarpaulin, which was shown in the turbine hall.

About his observations of the effect on the pandemic on the world, Mahama reflects that: “During the pandemic, we have realised that people are adapting more [towards] a socialist system, than a capitalist system, which is something I have always addressed in my work. This has changed the world and our sensibilities to the reality of our environment, seeing more people socially conscious than before.”

With cities gradually opening back up, the Biennale of Sydney was reopened in June and extended to September 2020.

“I have especially enjoyed sharing this passion for planting and growing my own food with close friends and my children.”

Temitayo Ogunbiyi

For Temitayo Ogunbiyi, a mixed-media artist living in Lagos, Nigeria, the lockdown was a period of reflection and care for her family. She spent a lot of the time reading preschool level assignments for her children, while thinking about holistic education for them that could include emotional development, compassion, generosity and care for our environment.

“I have especially enjoyed sharing this passion for planting and growing my own food with close friends and my children. Oh! I can’t forget all of the recipes that I’ve read over the past few weeks as we thoroughly explore cassava (fufu) flour, making everything from chewy chocolate chunk cookies, to savoury dumplings and crispy calamari batter,” she recalls. “My days revolved around them more than ever and it’s been comforting to remember that each day is a new beginning, and really not as far as we sometimes imagine.”

Ogunbiyi has also been making work though at a much slower pace, which, she says has been really good for her. “The period has also given me some time to thoroughly think around some ideas and approaches to art making that have been ruminating, underdeveloped for years in some cases. I continue to think about strategies for public play in light of how this new world might look.”

She adds that: “During this period, I’ve been reminded of the importance of physical activity for adults and children, focusing on playable models that could work within parameters that might be necessitated by the ongoing pandemic and address play through social justice.”

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s experience of the lockdown has brought to the fore certain ideas she had wrestled with for a few years. Like the importance of living modestly, keeping life simple materially and investing time in building a community.

“Since our child was born almost four years ago I’ve had this dream about living communally with other parents and schooling our kids communally, and this experience of lockdown, with our child’s school being closed, has really fast-tracked that, and we are deep in conversation with a few other parents of young kids, thinking about ways to make this a reality. And it’s happening.”

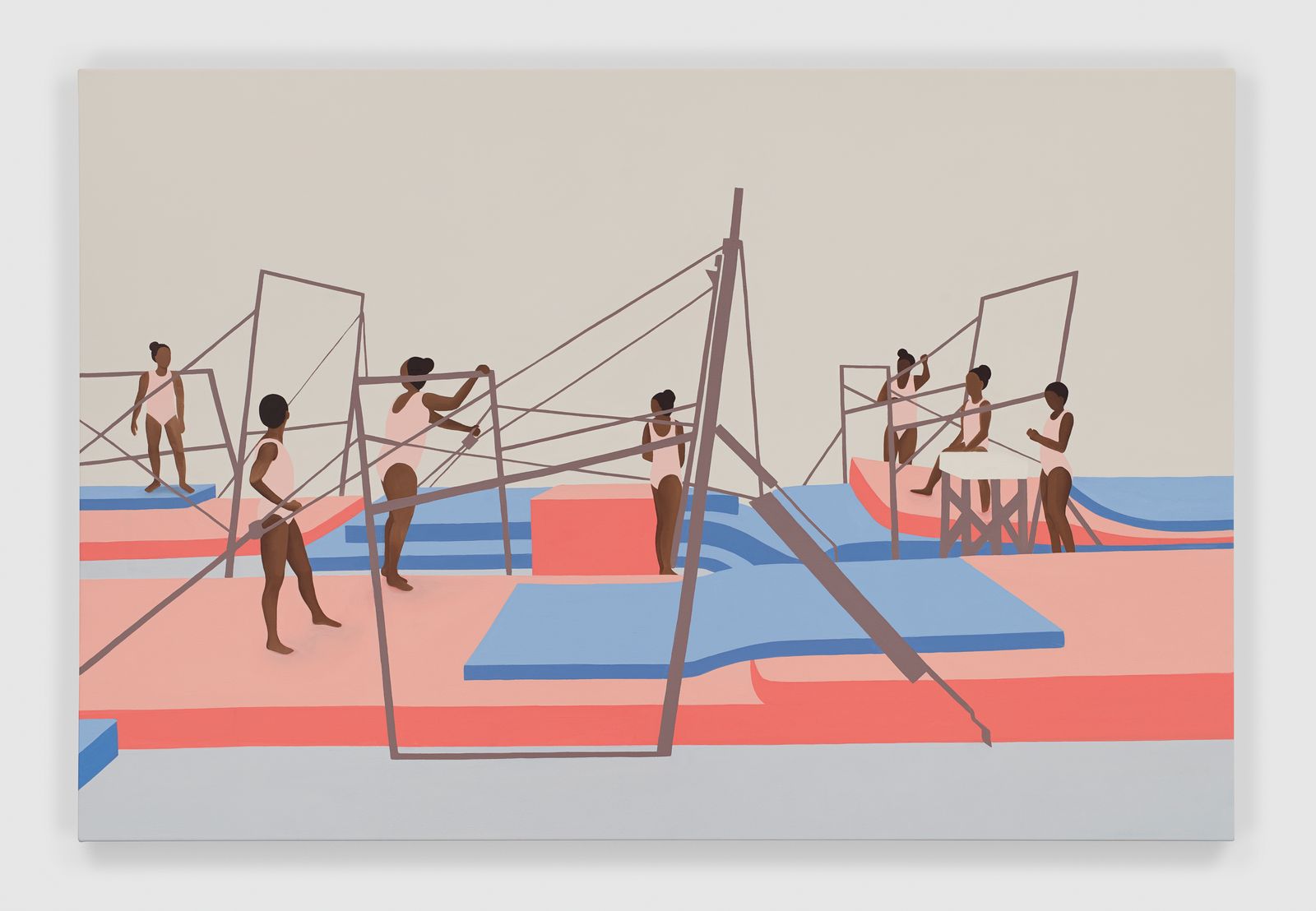

Nkosi’s first solo exhibition, Gymnasium at Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg, where she lives, was due to open March 26, 2020 but that was the day the lockdown was enforced in South Africa. They had to resort to opening the exhibition on Instagram which, to her satisfaction, gathered an intimate and discursive attendance.

Having had a meditation practice for a number of years Nkosi notes that a book that has been important for her during this time is Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation by Rev. angel Kyodo williams, Lama Rod Owens and Jasmine Syedullah. Being able to go through the collection of essays on meditation and Buddhism written through a frame of social justice and, importantly, written by Black people has been particularly helpful, she says.

Sharing insight on the current state of things, Nkosi states that: “Though the lockdown has been eased quite significantly in South Africa, we’re still taking it seriously, and doing our best to protect ourselves and our families. What I really miss is giving my parents a hug. They’re both definitely among the vulnerable groupings, because of their age, and it’s been many months without real contact.”

This period came with a particular challenge for portrait artist Tizta Berhanu who is based in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia. As with many artists, she had exhibitions cancelled – one at the Dubai Art Fair and a solo exhibition scheduled to take place in Addis Ababa last month – both she considered essential for her artistic development.

“When I first heard that the exhibitions were to be cancelled, I quickly lost my motivation and creative impulses, but then the stress begun to build up so I had to take up work again.” Berhanu is looking forward to when things return to what it was, where people can once again visit each other once again and visit gallery exhibitions. But for now, having just given birth, her days are filled with resting and looking after her newborn.

“I do not believe that humans are essential to the planet and its other elements. Without a healthy and balanced planet, we would not survive.”

Moufouli Bello

Moufouli Bello from Benin Republic was in the post-production phase of a digital work before the lockdown commenced. Hence, spent most of the time watching footages and building a narration for this project. She found value in the confinement as it allowed her work at a new pace void of urgency and stress. She also thinks this should be time for people to examine their role in preserving the planet.

“This period is the right time to reconsider our importance and place as living beings on earth,” she remarks. “I do not believe that humans are essential to the planet and its other elements. Without a healthy and balanced planet, we would not survive.”

“Perhaps, this is the cue we have been praying for, because we know a lot of things in the art world have needed to change for the better…”

Bright Ackwerh

Bright Ackwerh is known for his vivid and satirical illustrations. He experienced the lockdown in Accra, Ghana. Like Bello, this period was not critically disruptive to his practice and as such he could still create work unhindered, while simultaneously exploring new ideas. “Fortunately, I have never needed a very large setup to make work. So, being on lockdown and stuck at home still meant I could work well. Also, because I was privileged to have internet connectivity I could still connect with a few essential people and tap into discursive spaces to further polish any ideas that I had.” The period also afforded him time to initiate several projects that had been on hold.

Some of the challenges Ackwerh did have to deal with was shipping works bought by people outside the country. For the time being, it has been impossible but hopes that they will be patient enough to wait it out with him.

When asked about his thoughts on the changes that might be expected in the art world after the lockdown, Ackwerh says: “One beautiful thing about this though is that we are very uncertain about what the new normal is going to be like.”

“When we re-emerge, I would personally like to see a lot more independence in the way artists create and share their work. Perhaps, this is the cue we have been praying for, because we know a lot of things in the art world have needed to change for the better for a long time now.”